Visitors to USS Constitution today frequently ask about the small boats suspended from the ship’s quarter and stern davits. Minds no doubt filled with images of Titanic’s encounter with an iceberg, and they often wonder if these are lifeboats.

While the boats could be used to rescue some of the crew if the ship foundered, their real purpose was more mundane. Constitution’s officers and crew used the ship’s boats to communicate with people on shore, carry supplies, send boarding parties to other ships, or provide support for amphibious operations.

To facilitate these tasks, the U.S. Navy needed fast, sturdy boats. The whaleboat was the craft of choice. Whaleboats? Aren’t those used for hunting whales?

As their name would imply, whaleboats were in fact used to chase whales, but it was also a name given to a light, sturdy, double-ended boat. We have not yet discovered when the U.S. Navy began to use boats of this type, but by the War of 1812, many public vessels were provided with them.1 Constitution was no exception.

Receipts from New England boat builders give us a good idea of when they were purchased. Not surprisingly, the boats were produced in Massachusetts towns that had close ties to the whaling industry. In October 1812, Fairhaven, Massachusetts boat builder Barzillai Adams supplied three five-oar whaleboats to Constitution (two of them cost $50, and the third cost $55). Transporting them to Boston cost more than half the price of each boat.2 Mr. Adams also made boats for Hornet and Chesapeake. A few weeks later, William Lovering, Jr. delivered to the ship two whaleboats built by Charles Folger of Nantucket (these cost only $40 each).3

But just what did these boats look like? How much did they differ from the classic Beetle whaleboat used in the heyday of the New England whaling industry?

The first clue as to the appearance of Constitution’s whaleboats comes from a September 7, 1812 letter from Boston Navy Agent Amos Binney (the man charged with purchasing supplies for the navy’s ships) to boat builder Gideon Gardner:

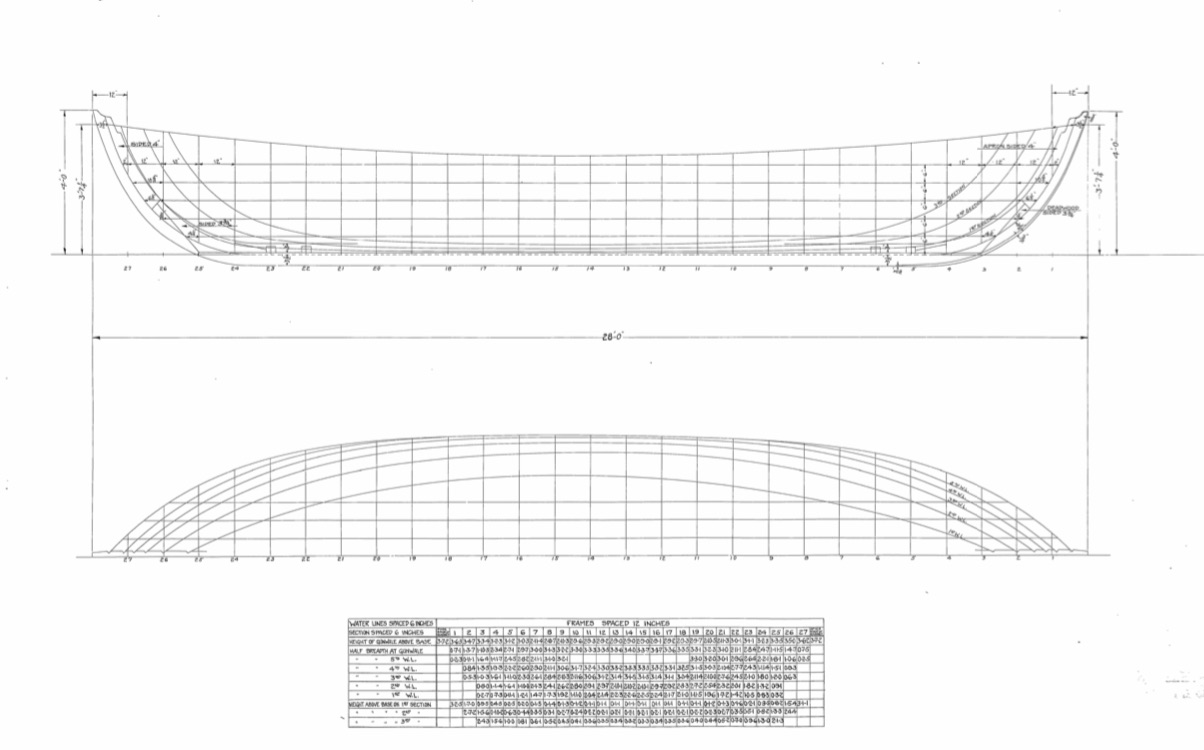

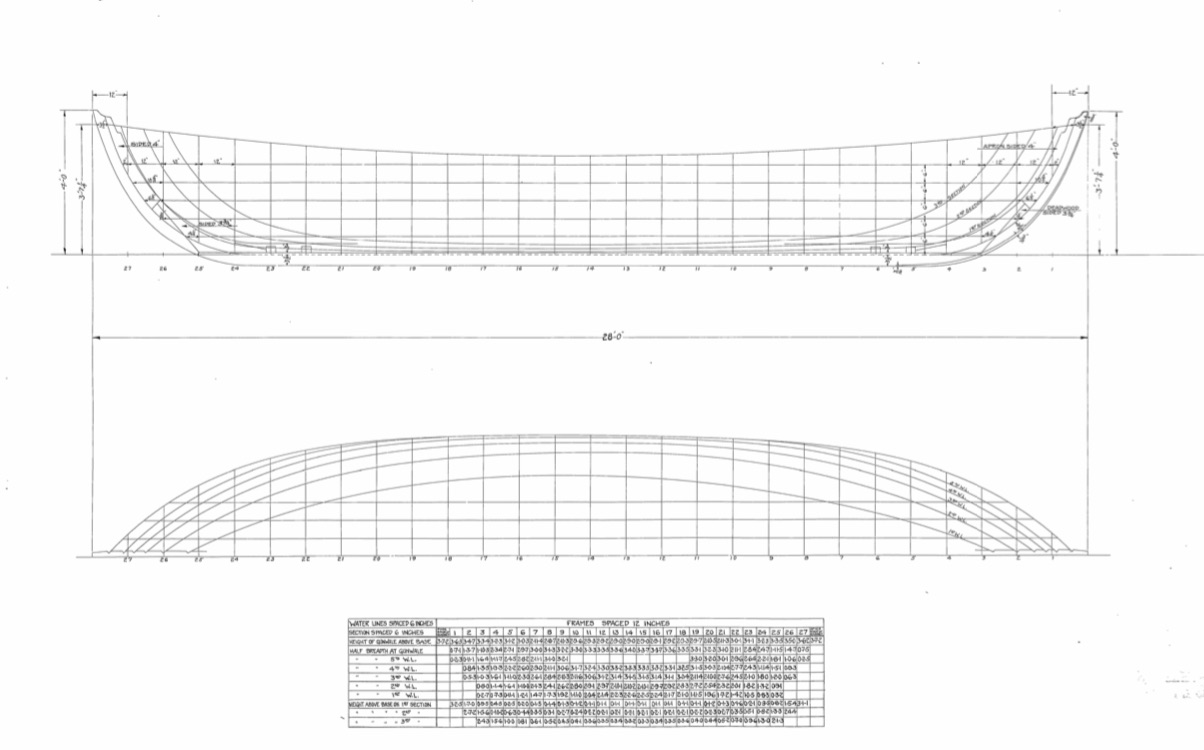

“Sir: Please to have Two Whale Boats of the same description as the last you furnished me built for the United States Frigate Constitution, let them be twenty eight feet in length, one to row with five and the other with Six oars, and if possible have them completed and sent on within fourteen days.”4

Today, Constitution once again carries whaleboats in her quarterdavits, but these are a twentieth century design built during the ship’s 1927-1931 restoration.

1 According to W.E. May, the Royal Navy did not adopt the whaleboat form until the end of the Napoleonic Wars. See The Boats of Men-of-War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999), 73-74.

2 Voucher to Barzillai Adams, October 3 and October 17, 1812, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, box 38, NARA.

3 Voucher to William Lovering, Jr., November 1812, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, box 38, NARA.

4 Amos Binney Letter Book, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts. It seems the ship did not receive these boats before sailing from Boston on August 2, 1812.

5 Voucher to Samuel Yendell, December 24, 1812, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, box 38, NARA; John Wade Account Book, 1811-1828, USS Constitution Museum Collection.

6 Voucher to Samuel Yendell, November 16, 1812, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, box 38, NARA.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.