USS Constitution‘s centuries of service provide us with a window through which we can look deeply into the past. There are moments in “Old Ironsides'” history that are prophetic, especially when viewed in hindsight. Such is the relationship of the U.S. Navy, USS Constitution, and Pearl Harbor.

In late 1845, Constitution was coming to the end of its World Cruise. Two and one-half years earlier, Captain John Percival, the commanding officer, had received his sailing orders from Secretary of the Navy David Henshaw in a January 22, 1844 letter which outlined the mission of the cruise.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Percival_31-089-598x1024.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Percival_31-089-598x1024.jpg)

“When the US frigate Constitution shall be…ready for sea, you will proceed…to the Eastern Coast of Africa, to look after the interests of American commerce along the Mozambique shore, and likewise along the islands of Madagascar, making yourself…familiar with the people, resources and commerce of those countries, and cultivating friendly relations with the inhabitants.”1

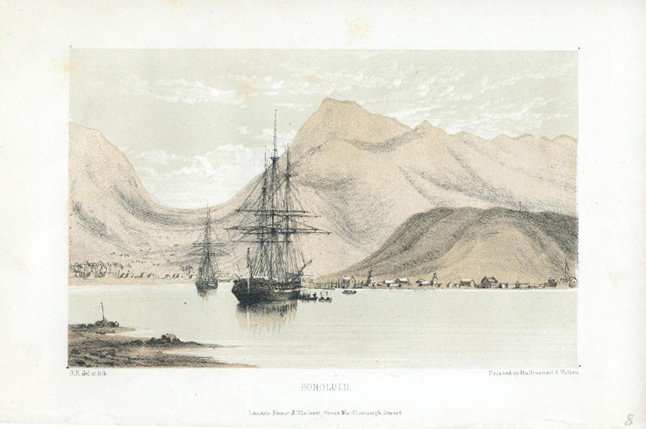

After Mozambique and Madagascar, Henshaw’s letter instructed Percival and his crew to continue to Borneo which “…[possessed] coal mines of great richness, both for quantity and quality.” In the 1840s, the United States Navy was slowly transitioning from a sail to steam navy. World-wide coal deposits overseen by or owned by the U.S. were instrumental in creating an effective and far-reaching steam-powered U.S. Navy. By the time Constitution arrived, however, a British special agent had already secured Borneo’s coal for the British Empire. Constitution continued its progress through southeast Asia, stopping at Cochin China (Vietnam), China, the Philippines, and Batan Island. Finally, Constitution dropped anchor in Honolulu on November 16, 1845.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1068-2_001.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1068-2_001.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1214-3_001.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1214-3_001.jpg)

Curtis wrote his report and sent it to Judd from Mazatlan, Mexico, where Constitution had sailed after leaving Hawaii. The Marine lieutenant, in his research, had visited the fort in Honolulu, built in 1816, and considered it too outdated for any use. Of the sites he toured, Curtis concluded that the mouth of the Pearl River, Pearl Harbor, was the ideal location for a fort. As he noted in his report, “If [fortifications] are built at all they ought to be made in such a manner and armed in such a manner as will last for ages. These are serious considerations that I should wish to impress upon your attention.”3 Curtis’ report even detailed that “Martello” towers were to be “armed…with thirty Paixhan Guns of the calibers of 10 inches shells & 68 lb shot” to complete the defenses.4 Many of the recommendations urged by Curtis were eventually taken up and built around Pearl Harbor.

Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898 and almost immediately the U.S. Army established its first outpost on Oahu.

“Increasing Japanese-American friction in the following decade led to a decision by the Army and Navy in 1908 to make Pearl Harbor the principal American naval bastion in the Pacific. To protect Pearl Harbor, the Army greatly expanded its Oahu garrison and in 1913 established the Hawaiian Department as an independent command under direct War Department control. In the two decades after World War I the Army…built up formidable coastal defenses…to protect Pearl and Honolulu harbors, and installed air defenses to guard vital installations…”5

![[Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston, 80-G-182874]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Aerial-view-of-the-Naval-Operating-Base-Pearl-Harbor-80-G-182874-1024x847.jpeg)

![[Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston, 80-G-182874]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Aerial-view-of-the-Naval-Operating-Base-Pearl-Harbor-80-G-182874-1024x847.jpeg)

Less than 100 years after Curtis’ report, the Empire of Japan attacked the U.S. Navy base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, killing 2,000 Americans and sinking 21 vessels of the U.S. fleet. On December 8, 1941, the United States declared war upon Japan in response to the December 7th attack, “a date which will live in infamy” in the history of the United States and, particularly, in the history of the U.S. Navy.

![[Caption]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/80-G-K-13512-1-1024x806.jpg)

![[Caption]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/80-G-K-13512-1-1024x806.jpg)

Leading up to and during the war years, USS Constitution remained in the Charlestown Navy Yard, but contributed to the war effort in its own way. In 1940, at President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s request (he was a former Assistant Secretary to the Navy and an “Old Ironsides” fan), Constitution, and the 1854 sloop-of-war Constellation were re-commissioned and designated symbolic flagships of the fleet. And during the war, Constitution was used as a place of confinement for officers awaiting courts martial.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection.]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1822-1_001-1024x809.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection.]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1822-1_001-1024x809.jpg)

USS Constitution, the USS Constitution Museum, and Boston National Historical Parks typically commemorate the anniversary of the bombing of the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7 with a ceremony aboard the WWII destroyer, USS Cassin Young. Holding the ceremony aboard the destroyer is most appropriate as its namesake, Commander Cassin Young, was the commanding officer of USS Vestal which was berthed directly alongside USS Arizona when the Japanese strike occurred on December 7th. Commander Young was thrown from his vessel when Arizona‘s forward magazine detonated. Dazed by the shock of the explosion, Young managed to climb back aboard Vestal and successfully beached his ship, thus enabling it to be salvaged later. USS Vestal served for the rest of the war and earned two Battle Stars. Commander Young was awarded the Medal of Honor “for distinguished conduct in action, outstanding heroism and utter disregard for his own safety, above and beyond the call of duty…” He was promoted to captain and received command of the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco. Eleven months after the attack at Pearl Harbor, Young was killed during the Battle of Guadalcanal when a shell from a Japanese battleship struck the bridge of San Francisco. Captain Cassin Young was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, the U.S. Navy’s second highest military decoration after the Medal of Honor.

1 Letter, David Henshaw to John Percival, January 22, 1844.

2 “The American Navy in Hawaii”, Albert Pierce Taylor, United States Naval Institute Proceedings, August, 1927.

3 J.W. Curtis to Honorable G.P. Judd, February 21, 1846, Archives of Hawaii.

4 Ibid.

5 Stetson Conn, Rose C. Engleman, and Byron Fairchild, Guarding the United States and Its Outposts (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army), 1964/2000.

The Author(s)

Margherita M. Desy

Historian, Naval History & Heritage Command

Margherita M. Desy is the Historian for USS Constitution at Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston.