Ranks + Rates

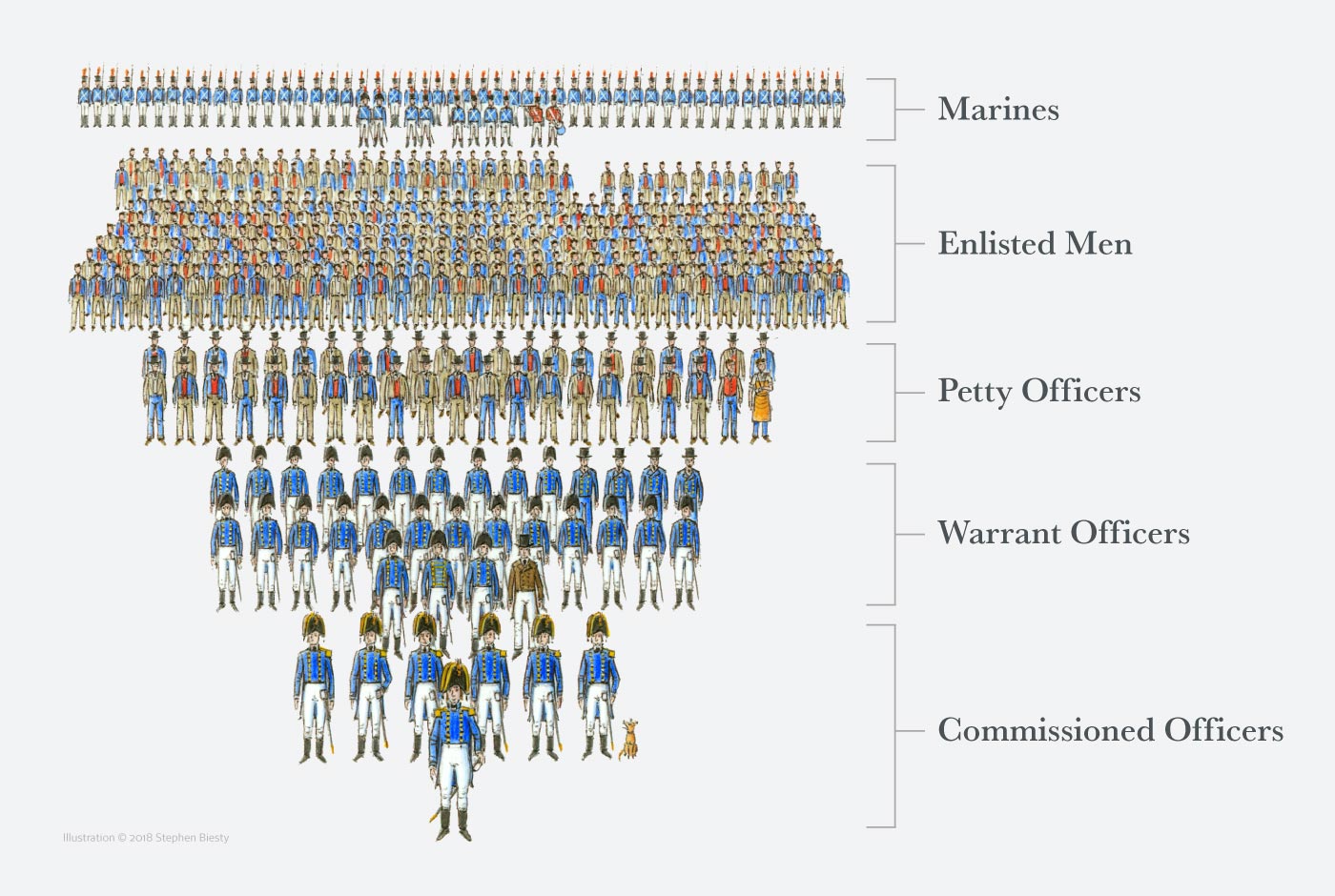

USS Constitution is a large and complex sailing warship, and during her active combat years it took 450 to 500 crew to keep her at sea. Today, there are 75 enlisted sailors and three commissioned officers assigned to USS Constitution.

From 1812 to 1815, a total of nearly 1,200 men served aboard “Old Ironsides.” Of the 450 to 500 men aboard for each cruise, about two-thirds were enlisted sailors, another 60 were Marines, and the rest were commissioned, warrant, or petty officers. Each rank and rate carried specific responsibilities to help the ship function efficiently at times of peace and war.

Commissioned Officers

- Captain

- Lieutenant

- Surgeon

- Surgeon’s Mate

- Purser

Captain

Captain was the highest rank in the navy during the War of 1812, and typically commanded ships of 20 guns or more. The captain had ultimate responsibility for the ship and crew. According to the official naval regulations issued to officers, the captain’s first duty was to prepare his ship for sea, which included making inventories of all stores and equipment, creating account books, recruiting a crew, and overseeing all the various tasks performed prior to a cruise. Once at sea, the captain was expected to have the ship ready for an engagement at all times and to oversee the training of the crew. In battle his station was on the quarterdeck, where he could direct the action. All decisions regarding navigation, sail handling, and fighting ultimately descended from him. The captain’s authority was law. Captains were also the highest paid officers, earning $100 per month and the right to eight rations per day.[1]

[1] Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America. January 25, 1802, 4-13.; and Names, rank, pay, and rations, of the officers of the navy and marine corps, 3 Feb. 1812, American State Papers: Naval Affairs: 1: 255-263.

Lieutenant

A 44-gun frigate, such as USS Constitution, carried between four and six lieutenants. The senior lieutenant was called the first lieutenant (equivalent to the executive officer today). The first lieutenant was the captain’s second in command to whom great power and responsibility were delegated. In the captain’s absence, the first lieutenant was in command of the ship. He did not stand watch like the rest of the crew, but was, like the captain, always available. It was the first lieutenant’s duty to see that the captain’s orders were carried out satisfactorily. The smooth running of the ship depended on his organizational skills. The first lieutenant created the watch and quarter bills and oversaw the ship’s maintenance. All others on the ship reported to the first lieutenant, who in turn made regular reports to the captain. During special or delicate evolutions, such as getting underway or anchoring, he had command of the ship. In battle, most commands were passed from the captain to the first lieutenant. All told, the first lieutenant was a very busy man; he rarely left the ship and was never away overnight.[1] The lieutenant received $40 per month and three rations per day.[2]

The junior lieutenants (second, third, fourth, etc.) each had command of a watch. The junior lieutenant kept a list of the officers and men in his watch, all of whom were under his care and command. When mustered, he examined the men to make sure they were well clothed, clean, and sober. He regularly visited the lower decks to make sure the sentries were at their posts, that no tobacco was smoked between decks, and that there were no unenclosed candles lit. While at sea, a junior lieutenant was not to change the ship’s course without the captain’s permission, unless it was to prevent a collision or other accident. In battle, the lieutenants were stationed with their divisions on the spar deck or gundeck. The youngest lieutenant exercised the men in small arms and oversaw the use of small arms in battle. In addition, all lieutenants were required to keep a journal or log, a copy of which was delivered to the navy office at the end of a voyage.[3]

[1] Tyrone G. Martin, A Most Fortunate Ship: A Narrative History of Old Ironsides (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 70-71.

[2] “Names, rank, pay, and rations, of the officers of the navy and marine corps, 3 Feb. 1812” in American State Papers, Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 255-263.

[3] Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 13-15.

Surgeon

Surgeons were responsible for the health of the crew and shipboard hygiene. It was the surgeon’s duty to oversee the procurement of medicines and stores for the ship’s hospital department. He visited his patients at least twice daily and informed the captain of their progress. He also kept two journals, one of his surgical practice and one of his physical practice, and sent them to the Navy Department at the end of each cruise. When the ship beat to quarters, the surgeon and his mate repaired to the cockpit, on the orlop deck, where they laid out the operation tables and instruments. When battle was not imminent, the surgeon was usually in the sick bay, located forward on the berth deck.[1] The surgeon’s expertise was appreciated and he was paid accordingly at $50 per month with the option of taking two rations per day.[2] Many surgeons provided their own instruments and paid for medicines out of their own pocket. They expected to be reimbursed for these expenses, however. A passage in Surgeon Amos Evans’ journal suggests the procedure: “Went on shore to the Navy agent’s with a requisition & from thence to the Apothecary shop and bargained for the medicines.”[3]

[1] J. Worth Estes, Naval Surgeon, Life and Death at Sea in the Age of Sail (Canton, Mass.: Science History Publications/USA, 1998), 58-65.

[2] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 490-491.

[3] Amos A. Evans, Journal Kept on Board the Frigate Constitution 1812, ed. William D. Sawtell (Concord, Mass: Bankers Lithograph Co., 1967), 385.

Surgeon’s Mate

The surgeon’s mate assisted the surgeon in his duties (see Surgeon). The surgeon’s mate was akin to the modern medical student gaining valuable on-the-job training. Surgeon’s mates berthed in the cockpit[1] (or steerage) and ate there with the warrant officers. They received $30 per month plus two rations per day.[2]

[1] J. Worth Estes, Naval Surgeon, Life and Death at Sea in the Age of Sail (Canton, Mass.: Science History Publications/USA, 1998), 38.

[2] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 490-491.

Purser

The purser was the ship’s business agent, paymaster, grocer, and shopkeeper rolled into one. His duties, which required him to be highly organized and exercise good business sense, included keeping the ship’s pay and muster rolls and paying the officers and men. He was in charge of procuring and issuing provisions to the crew. In addition, the purser ran a ship’s store from which the men could by clothing, toiletries, utensils, knives, ribbon, needles, thread, mustard, chocolate, coffee, tea, sugar and tobacco. To keep track of all this, navy regulations required the purser to keep detailed account books.[1] During battle, the purser was stationed in the cockpit to help the surgeon dress the wounded. Pursers received $40 per month and two rations per day.[2] Beyond the purser’s annual compensation, he could realize great gains selling clothing and supplies to the crew while at sea. With no competition and a captive market of about 450 men and boys aboard a frigate, there was room for extraordinary profiteering.

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 31.; and Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802).

[2] “Names, rank, pay, and rations, of the officers of the navy and marine corps, 3 Feb. 1812” in American State Papers, Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 255-263.

Warrant Officers

- Chaplain

- Sailing Master

- Master’s Mate*

- Boatswain

- Gunner

- Carpenter

- Sailmaker

- Midshipman

- Captain’s Clerk

- Schoolmaster

Chaplain

Education, rather than religious fervor, was a prerequisite for a chaplain’s commission in the early American navy. Few navy chaplains were ordained ministers, but most were college educated. It is true that the chaplain was required to read divine service at Sunday muster and perform funerals, but the chaplain’s most important duty was to serve as a schoolmaster to the midshipman and teach them writing, arithmetic, navigation, and sometimes foreign languages. On squadron flagships, the chaplain often served as the commodore’s secretary. Most chaplains served in the navy for a year or less. They were paid $40 per month and received two rations per day.[1]

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 31.; and Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 18.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Sailing Master

The sailing master was responsible for the day-to-day running of the ship. He had to be an excellent seaman and navigator, and well-versed at working and maintaining a vessel at sea. Navigation was his direct responsibility, and he was in charge of keeping the logbook and charts. In addition, he kept a journal in which he noted navigational challenges or dangers not marked on charts, and inventories of stores and provisions brought aboard and used. He oversaw the loading and stowing of ballast, provisions, and other cargo, and was responsible for keeping the ship in good sailing trim. The master’s mates, boatswain, and carpenter reported to the sailing master. Because a sailing master held his rank by virtue of a warrant from the Navy Department rather than a commission, his was a nonpromotion-track position. He was paid $40 per month and was allowed two rations per day.[1]

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 31.; and Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 15-16.

Master’s Mate*

Master’s mates were assistants to, and under the direction of, the sailing master. A master’s mate was in charge of the log line and glass by which the ship’s speed was recorded. He made regular entries in the log, and saw to the adjustment of the forward sails. He also attended to the stowage of the anchor cables, making sure they were clean and well coiled so as to be let out quickly when needed. The master’s mate was also well-versed in stowing ballast and provisions in the ship’s hold.[1] He received $20 per month and two rations per day.[2]

*Prior to an Act of January 2, 1813, master’s mates were rated as petty officers.[3]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 192.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

[3] U.S. Congress, An Act to increase the Navy of the United States, 12th Cong., 2nd sess., ch. 6, approved January 2, 1813.

Boatswain

The boatswain (pronounced “bosun”) was responsible for the ship’s boats, sails, rigging, colors (flags), anchors, and cables. The ship’s rigging was his principal concern. He made sure that all the standing rigging and masts were set up properly, and that the running rigging was in good condition. He surveyed the sails to see that they were properly attached to the yards or stays and that they were well furled. He also acted as a sort of foreman for the crew, summoning the men to their duty, guiding them in their work, and seeing that the work was done with the least possible noise. The boatswain traditionally carried a silver call (or whistle) on a lanyard around his neck as a badge of office. In battle he was stationed on the forecastle.[1] The boatswain was paid $20 per month and received two rations per day.[2]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 41.; and Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 18-19.; and Tyrone G. Martin, A Most Fortunate Ship: A Narrative History of Old Ironsides (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 73.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Gunner

The gunner was responsible for all of the ship’s guns and their equipment, small arms, gunpowder, shot, and magazine tools. Gunpowder is highly flammable, so great attention was paid to properly securing the powder magazine; the captain kept the keys, and only the gunner was allowed to open the space. The gunner also supervised gunnery drills and in some cases small arms drills. In battle, the gunner’s station was the magazine, where he oversaw the filling and passing of cartridges.[1] He made $20 per month and two rations per day.[2]

[1] Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 19-22.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Carpenter

The carpenter was in charge of the wooden fabric of the ship, including the hull and its fittings, the masts, yards, boats and all other wooden equipment. It was his duty to see that the ship remained free of leaks, and he regularly surveyed the decks, sides, and hold to ensure the caulking was in good shape. If the ship took on water, he oversaw the manning and running of the pumps. In battle the carpenter stationed himself below decks, where he and his mates could plug shot holes or affect other temporary repairs to keep the ship in a fighting trim. The carpenter made $20 per month and received two rations per day.[1]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 78.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Sailmaker

The sailmaker was in charge of the ship’s sails and their associated gear. A ship’s suit of sails was typically made ashore by master sailmakers, but the shipboard sailmaker had to be able to repair any damage that might occur from the violence of either the weather or the enemy. Sails of flax or hemp had to be aired frequently to prevent them from rotting. Much of the sailmaker’s time was spent overhauling the sail locker to ensure adequate air circulation, and ensuring that shipboard vermin did not attack the sails. Besides the sails, the sailmaker was expected to make and repair various tarpaulins, wind sails, hammocks, hammock cloths, awnings, and any other canvas items required for the ship. The sailmaker made $20 per month and received two rations per day.[1]

[1] Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix; Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 19.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Midshipman

Midshipmen were officers in training. Drawn from the ranks of the middle class, they went to sea to learn seamanship and leadership. They received some formal training in mathematics, languages, and literature from the schoolmaster or chaplain, but most of their education was hands-on. In time, if they mastered their trade, they could expect to receive a lieutenant’s commission. Midshipmen had no specific duties as such, but were expected to do whatever was ordered of them. This could include supervising the men aloft, running orders for the officers, co-commanding a division in battle, sending and receiving signals, or standing a watch. In addition to their various shipboard duties, midshipmen were expected to keep a journal of every cruise, in which they recorded essential information and observations.[1] Midshipman were paid $19 per month and got only one ration per day.[2]

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 131-133.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Captain’s Clerk

The captain’s clerk was not officially a naval officer: he carried no warrant or commission, but was appointed by the captain for a specific period. Most were fairly well educated, had good penmanship, and perhaps some book-keeping experience. The clerk’s duties included making neat copies of the captain’s letters, preparing routine paperwork, and keeping the ship’s books. For many young men, a clerkship was the first step toward procuring a midshipman’s warrant or a pursership. The clerk slept on the berth deck with the midshipman, was paid around $25 per month, and received one ration per day.[1]

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 31-32, 101-102.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Schoolmaster

During the first decade of the U.S. Navy’s existence, some ships carried a schoolmaster whose duty it was to teach the boys and midshipmen the rudiments of a liberal education. Around 1802, the rank of schoolmaster and chaplain seemed to have merged, and thereafter the chaplain assumed the former duties of the schoolmaster.[1]

No schoolmasters served aboard USS Constitution during the War of 1812.

[1] Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 31.

Petty Officers

- Master-At-Arms

- Ship’s Corporal

- Quartermaster

- Steward

- Cook

- Boatswain’s Mate

- Coxswain

- Boatswain’s Yeoman

- Gunner’s Mate

- Quarter Gunner

- Armorer

- Gunner’s Yeoman

- Carpenter’s Mate

- Cooper

- Carpenter’s Yeoman

- Sailmaker’s Mate

Master-At-Arms

The master-at-arms acted as the chief of security aboard ship. When prisoners were captured, he saw to their confinement and placed sentries over them. He roamed the deck at night, making sure all fires and candles were extinguished and that there were no “irregularities” in the ship. When a boat from shore or another ship came along side, the master-at-arms was to stand in the gangway to ensure that no liquor or other forbidden items were smuggled aboard, and that none of the crew attempted to desert. Also, as his title would suggest, the master-at-arms taught the use of the ship’s small arms to both officers and crew, and together with the armorer made sure the arms were kept in good order. The master-at-arm’s pay was $18 per month and one ration per day.[1]

[1] Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 23.; and William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 191.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Ship’s Corporal

The ship’s corporals were subordinate to the master-at-arms and performed many of the same duties. They assisted with teaching the small arms drill to the crew and, when a boat came along side, made sure that no “spirituous liquors” were brought into the ship. Fire prevention was their special purview. At “lights out” they went around the ship extinguishing all candles and fires save those in the care of the sentries. In the night, they patrolled the lower decks to ensure that all the crew were in the proper place.[1] They were likely paid as able seamen, receiving $12 per month.

No ship’s corporals are listed on USS Constitution’s muster rolls during the War of 1812, but some trustworthy seamen may have been unofficially appointed by the captain to fulfill this roll.

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 88.

Quartermaster

The quartermaster was appointed by the sailing master and assisted the master’s mates with their duties. He helped supervise the stowage of ballast and provisions, coiled the anchor cables in the tier, supervised the men at the wheel, and kept time with the watch-glasses.[1] A quartermaster made $18 per month and received one ration per day.[2]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 226.; and Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Steward

The steward was hired by the purser to help with the distribution and administration of the ship’s provisions and slop stores. His primary duty was to issue daily rations to the mess cooks and keep track of other goods received on board and issued to the men.[1] Officially, a steward was paid $18 per month,[2] but a wise purser might pay more out of his pocket to get and keep a trustworthy man.

[1] Hezekiah Loomis, Journal of Hezekiah Loomis,: Steward on the U.S. Brig “Vixen”, Captain John Smith, U.S.N.; war with Tripoli, 1804, ed. Louis F. Middlebrook (Salem, Mass: The Essex Institute, 1928).

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Cook

The cook occupied an important position aboard ship: feeding the crew. His role was more supervisory than participatory, though, and he did not actually cook original dishes from scratch. The cook oversaw the steep tub (the barrel in which the salt meat was allowed to soak before cooking), tended the fire in the camboose (stove) to ensure the food was roasted, baked, or boiled properly, and oversaw the scouring of the copper boilers in which the crew’s rations were prepared. The selling of slush, the grease and fat that rose to the surface of the boilers during cooking, was his special privilege, but he first had to provide the boatswain with all that was needed for lubricating various moving parts on the ship. The cook received $18 per month.[1]

[1] Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.; and Naval Regulations Issued by the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (Washington: 1802), 24.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Boatswain’s Mate

The boatswain’s mates (pronounced “bosun”) were subordinate to the boatswain and aided him with his duties (see Boatswain). They were specifically bidden to keep the men at their allotted tasks. Like the boatswain, they carried silver calls (or whistles) with which to give commands. Many boatswain’s mates carried short, knotted pieces of rope called “starters” or “colts” with which they would strike crew members who were slow or awkward in their duties. It was also the boatswain’s mates’ duty to flog malefactors (who were duly convicted) with the “cat-of-nine-tails.” Boatswain’s mates received $19 per month.[1]

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 135-136.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Coxswain

The coxswain (pronounced “cock-sin”) had nominal command of a ship’s boat, its crew, and all the equipment belonging to it. Typically, the coxswain had charge of the captain’s barge or gig, and saw that the boat was kept in good condition. He had a whistle to call away the boat’s crew when needed. In the boat, he sat in the stern and steered.[1] A coxswain made $18 per month.[2]

[1] William Burney, Falconer’s New Universal Dictionary of the Marine (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006), quoted in Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 137.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Boatswain’s Yeoman

The boatswain’s yeoman (pronounced “bosun”) was subordinate to the boatswain and took care of the storeroom that held all of the boatswain’s stores and supplies. He was responsible for the stowage, account, and distribution of all of those stores, and kept the room locked when not in use.[1] The boatswain’s yeoman made $19 per month.[2]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 328.; and Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 136-137.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Gunner’s Mate

The gunner’s mates worked under the supervision of the gunner. They focused their energies on maintaining the guns and equipment: painting and greasing carriages, scaling (removing rust) from the guns, filling cartridges, etc.[1] Gunner’s mates made $18 per month.

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 136.

Quarter Gunner

Quarter gunners were supervised by the gunner’s mates. Most ships carried one quarter gunner for every four guns. Their duties were similar to those of the gunner’s mates, but they were also considered prime seamen and often found themselves keeping watch and supervising tricky sail handling maneuvers.[1] Quarter gunners made $18 per month.[2]

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 136.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Armorer

The armorer was a skilled blacksmith able to repair or forge anew all of the metal work aboard ship. He was supplied with a set of tools and a portable forge. He kept in good order the cannon locks and hand-cuffs. The armorer was also responsible for maintenance of the ship’s and Marines’ muskets, and answered to the Marine officers and gunner.[1] The armorer made $18 per month.[2]

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 139.; and Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Gunner’s Yeoman

The gunner’s yeoman was subordinate to the gunner and took care of the storeroom that held all of the gunner’s stores and supplies. He was responsible for the stowage, account, and distribution of all of those stores, and kept the room locked when not in use.[1] The gunner’s yeoman made $19 per month.[2]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 328.; and Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 136-137.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Carpenter’s Mate

The carpenter’s mates assisted the carpenter with all of his duties. They were usually skilled men who had learned the trade ashore or in the merchant service. They worked alongside the carpenter as he surveyed the hull and decks, sounded the well, or attended the pump. The mates prepared lead sheathing and plugs to stop up shot holes created in battle, and knew how to fish (repair with a splint) damaged masts and yards. Carpenter’s mates made $19 per month.[1]

[1] Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.; and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Cooper

In an age in which everything was packed and shipped in wooden barrels, the cooper was an essential member of a ship’s company. A cooper trained for years to master the construction of some 240 different sizes of casks and barrels. Aboard ship, his primary responsibility was surveying the water and food containers to see that they remained tight and did not leak their contents into the hold. A navy cooper rarely made large casks, but spent most of his time opening provisions for the purser and breaking down empty casks. Often, coopers did not have enough work to occupy their time and so assisted the steward with his work.[1] The cooper made $18 per month.[2]

[1] Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.; and Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 139.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Carpenter’s Yeoman

The carpenter’s yeoman was subordinate to the carpenter and took care of the storeroom that held all of the carpenter’s stores and supplies. He was responsible for the stowage, account, and distribution of all of those stores, and kept the room locked when not in use.[1] The carpenter’s yeoman made $19 per month.[2]

[1] William Falconer, Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780): A Reprint (New York: A. M. Kelley, 1970), 328.; and Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 136-137.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Sailmaker’s Mate

The sailmaker’s mate assisted the sailmaker. He performed most repairs on a vessel’s sails and supervised seamen who frequently assisted in sewing long seams. He stowed sails in the sail locker and attached tallies to allow them to be quickly identified. The sailmaker’s mate also aired and dried sails to keep them from rotting.[1] The sailmaker’s mate made $19 per month.[2]

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 139.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Enlisted Men

- Able Seaman

- Ordinary Seaman

- Boy

Able Seaman

The able seamen were the elite members of the enlisted crew. Having sailed for years on merchant vessels or worked their way up through the ranks in the navy, it was on the able seamen that the officers relied for the smooth operation of the ship. The traditional requirements for an able seaman were that he be able to hand (furl or take in a sail), reef (reduce a sail’s area), and steer. In addition, he was expected to be familiar with nearly all aspects of shipboard labor. He had to be able to cast the sounding lead, sew a sail with a palm and needle, and understand all parts of the rigging and the stowage of the hold. Furthermore, he had to know how to fight as part of a gun crew or with small arms. It was from the ranks of the able seamen that the petty and warrant officers were drawn. An able seaman made $12 per month and many received a $20 bounty on enlistment.[1]

[1] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Ordinary Seaman

Among the enlisted men, ordinary seamen stood in the middle of the lower-deck hierarchy. These men had typically sailed one or two voyages and knew basic seamanship. Like the able seamen, they too could hand (furl or take in a sail), reef (reduce a sail’s area), and steer, but some of the more complicated maneuvers were foreign to them. Many ordinary seamen were numbered among the topmen, the young and agile crewmembers who were responsible for working aloft on the masts and yards.[1] The ordinary seaman made $10 per month.[2]

[1] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793-1815 (Annapolis, MD, Naval Institute Press: 1989), 133.

[2] “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Boy

The rank of boy had nothing to do with age, but rather experience. The majority of boys were in their mid- to late-teens. They were in effect apprentice seamen, learning the ways of the ship on what was most likely their first cruise. The rank was equivalent to “landsman” in the Royal Navy. The boys composed one part of that class of sailors referred to (sometimes derisively) as “idlers,” meaning that they stood no regular watch, except when “all hands” were called. Other duties assigned to boys included attending the watch glass and bell, running messages, and acting as servants for the officers. They coiled the running rigging after sail evolutions and were often sent aloft to furl or loose the light sails. Much of the routine maintenance of the ship, such as sweeping, scrubbing, and slushing the masts, fell to the lot of the boys. In the course of these duties they were learning rudimentary seamanship, especially knots and splices. In battle, some of the boys passed powder or shot to the guns. Boys made from between $6 and $10 per month.[1]

[1] General Orders U.S.S. Independence 1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Historical Foundation, 1969); and “Estimate of the pay and rations of the officers and crew of a ship of war of seventy-four guns for twelve months, 17 Dec. 1811” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 251.

Marines

- Lieutenant

- Sergeant

- Corporal

- Private

- Musicians

Lieutenant

The lieutenant of Marines was in charge of the ship’s Marine detachment. Among his men, his command was supreme, but in terms of the shipboard hierarchy, the Marine lieutenant was subordinate to the ship’s captain and officer of the watch. His duties were those that directly related to the supervision and training of the Marine detachment. Every evening he inspected the men to see that they were clean, sober, and in good health. He frequently trained the men at the manual of arms and occasionally allowed them to fire at a target. He ensured that a guard was properly formed and saw the sentries posted in the proper places around the ship. In battle, the Marine lieutenant formed up his men in the waist of the ship to act as sharpshooters or to repel boarders.[1] A Marine lieutenant made $30 per month.[2]

[1] General Orders U.S.S. Independence 1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Historical Foundation, 1969).

[2] “Marine Corps, 12 Feb. 1821” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 738.

Sergeant

The Marine sergeant was a non-commissioned officer who supported the Marine lieutenant in his duties. He was the one who actually gave the commands to the Marines. He conducted daily small arms drills and ensured that the men were well dressed and that their equipment was well maintained. He checked to see that the sentries were at their posts and could lead detachments of Marines in battle. For his work, a sergeant received $10 per month.[1]

[1] Thomas Truxton, Remarks, Instructions, and Examples, Relating to Latitude and Longitude, etc. (Philadelphia: 1794), appendix.

Corporal

Like the sergeant, the Marine corporal was a non-commissioned officer who supervised the men on a more intimate level. He lived and fought alongside the Marine privates under his command, and assisted and directed all of the various duties of the Marines. A corporal received $9 per month.[1]

[1] “Marine Corps, 12 Feb. 1821” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 738.

Private

Marine privates served as the shipboard police force and were, in effect, sea-going soldiers. They used the same manual of arms as the army and trained in much the same way. Unlike the army, Marines were familiar with naval work and warfare. Marines could not be ordered aloft to do the work of the seamen there, but they were expected to man the capstan or serve as gun crews on the gundeck. Marines stood watch as sentries at sensitive parts of the ship to see that no unauthorized people passed into those spaces (such as the captain’s cabin or the spirit room). In battle, Marines armed with muskets or rifles took up station along the gangway or in the tops to keep up a constant fire on the enemy’s decks. The Marine private received $6 to $8 per month.[1]

[1] “Marine Corps, 12 Feb. 1821” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 739.

Musicians

The Marine fifer and drummer were essential members of a ship’s crew. Amid the thunder of battle, their shrill piping or deep drumming were used to pass orders to the crew. The instruments were also used before a battle, to call the men to quarters. In more peaceful situations, the musicians might play to lighten the load or give cadence to heavy work such as raising an anchor or a boat. The Marine musicians were paid $8 per month.[1]

[1] “Marine Corps, 12 Feb. 1821” in American State Papers: Naval Affairs, Volume 1: 738-739.