As we’ve begun to expand our understanding of USS Constitution’s 1812 crew, we’ve learned that the shipboard lives of the officers, sailors, and Marines is only one part of a complex story. Though it was the men who fought the battles and suffered physical wounds, for the women left at home — wives, sisters, and mothers — the war brought its own traumas and hardships.

The letters exchanged by USS Constitution Purser Thomas J. Chew and his wife, Abigail, give us a glimpse into the personal lives of one upper middle class family and how they coped with the stresses of wartime. Both were exquisitely literate, and they wrote their letters in the lively, conversational tone so common at the time. In keeping with their playful nature, Abigail frequently signed her letters “your attached Hortensia,” a reference to a famous female orator of the Roman Republic. For his part, Thomas signed his letters, “your loving husband.”

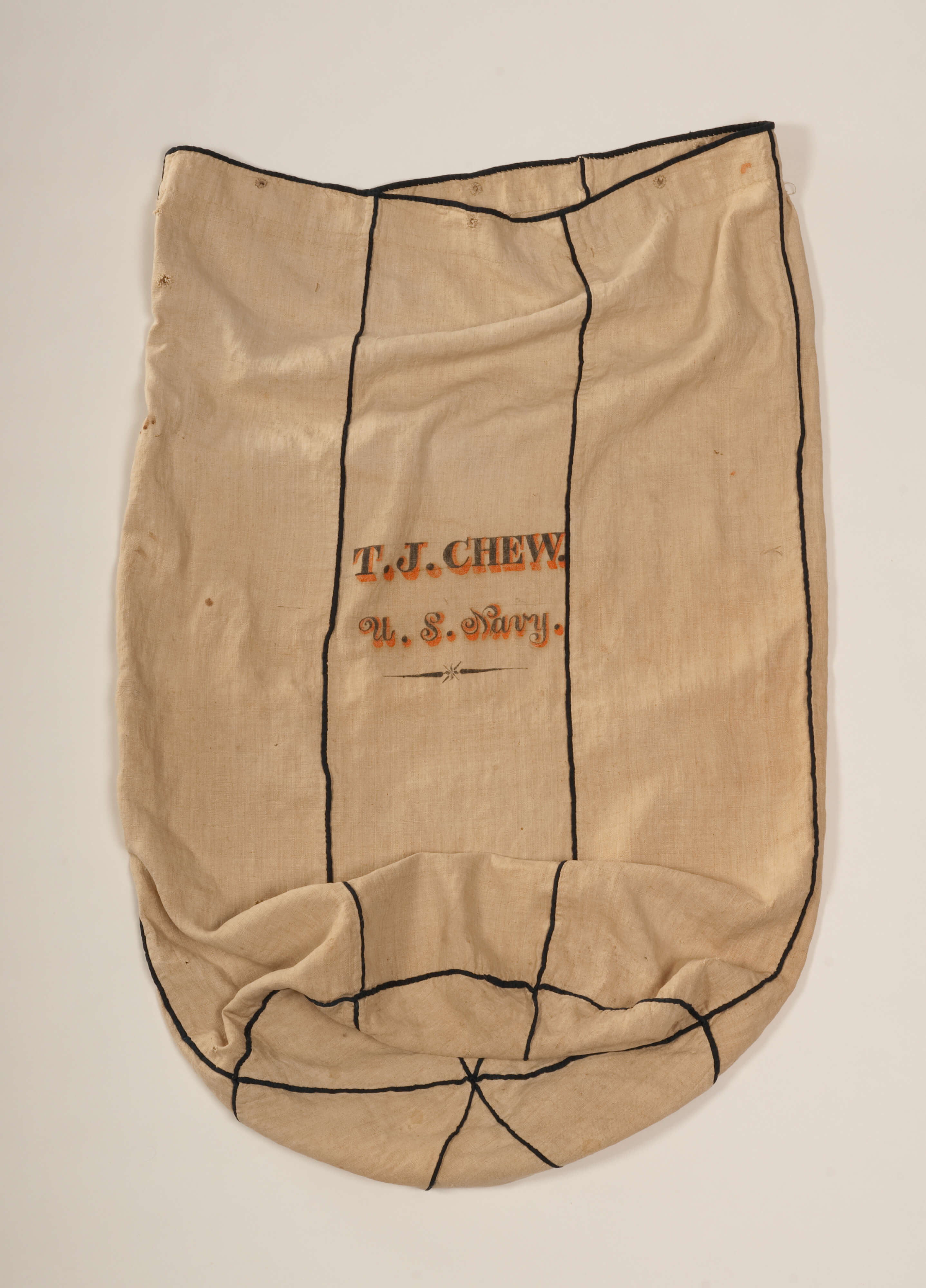

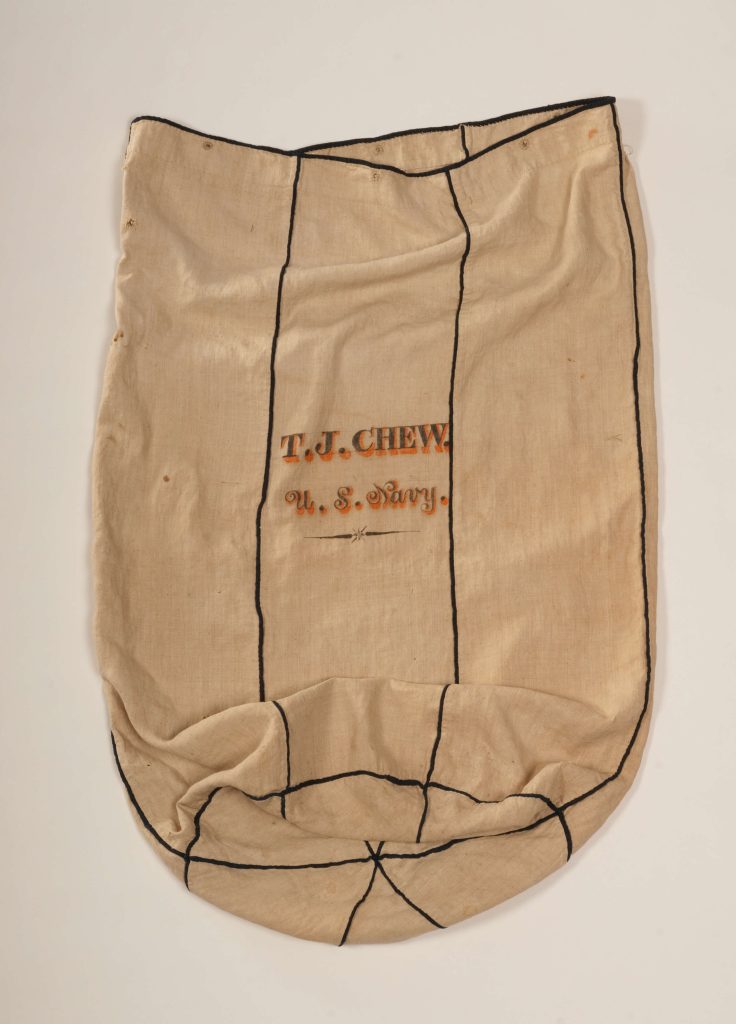

Chew had secured a U.S. Navy purser’s commission in 1809 and joined Constitution’s crew on June 1, 1812. Thanks to Thomas’ position and other investments, the Chews were financially comfortable, and did not suffer from the acute poverty that afflicted so many sailors’ families. Nevertheless, Abigail never became accustomed to Thomas’ frequent absences, nor reconciled to the dangers of his job. He came home briefly after Constitution’s successful battle with HMS Guerriere but was soon appointed to the ill-fated Chesapeake, commanded by his friend James Lawrence.

On June 1, 1813, Abigail sat to write to her husband, never guessing that at that very moment, the Chesapeake was engaged in a bloody battle with HMS Shannon. She wrote, “to assure you I continued to feel as cheerful as our separation would admit – I will not indulge myself with gloomy fears – but anticipate the pleasures your safe return, will, certainly produce -…adieu my Dear husband may heaven watch over & protect & may you soon be returned to the arms of an affectionate wife.”1

The American ship surrendered to the British. Stationed down below to oversee the moving of cartridges from the magazine to the guns, Thomas survived unscathed, but he was present when Captain Lawrence issued his final command: Don’t give up the ship.

While worry and anxiety compelled Abigail to write to her husband, she sometimes wished to share with him the seemingly little details of life and family that he missed while away at sea. After the birth of their son, James Lawrence, (named, of course, after Thomas’ slain friend), Abigail kept Thomas abreast of his development: “You have ‘ere this received a letter from me & heard that Lawrence & myself were well – we continue to be so & the little fellow looks quite plump…to day he is four weeks old & weighs 7lb 1oz…”2 Only six days later, Abigail updated Thomas: “The boy continues well & to grow, his eyes are very brilliant and appear quite strong, his mouth, Tho’ not entirely well, is not troublesome. – his aunts discover daily new beauties.”3

A week later, Abigail wrote again: “My little Lawrence is not taking his morning naps-…he is becoming a more substantial boy every day – he now weighs 8 ½, which is gaining very fast. Indeed he is a beautiful boy & looks just like his dady [sic].”4 Stationed far away at Sackets Harbor, New York, Thomas could only picture his son from the details Abigail gave him.

Though surrounded by a support system of family, friends, and neighbors, Abigail often felt the private pain of loneliness occasioned by her separation from Thomas, even for only a few days. On September 9, 1814, Abigail confided to a friend, my “husband left me very early yesterday morning for Portland, being Prize Agent for the Enterprize, & will not return till Saturday night-…To morrow is the anniversary of my wedding- I regret husband will not be with me that we might make merry together- I shall take my wine alone….”5

The distance could be frustrating in other ways. With no sure way to deliver letters rapidly, if indeed they ever reached their destination at all, weeks could pass before news arrived home. In a half-scolding, half-teasing way, Abigail expressed her frustrations at visiting the post office, only to find that there were no letters waiting for her: “What must I think of your uncommon silence – neglect, I will not think it – you have never before given me cause to complain so justly- 3 weeks on Tuesday since you left & only one short letter of etiquette – surely I have not become less dear to you since your return from the Harbour – no my dear husband, I think too well of myself, to suppose your affection will cool easily- I must still think there is a detention of the mails & hope to morrow will be more propitious.” The hoped for letters came a few days later, and Abigail could write, “At length, my dear husband, are my wishes gratified, & the reception of two letters this morning, have given me a new spring to my feelings- I find I must rail at the bad roads, & not again think you negligent.”

After long months of separation, the hope of an imminent reunion enthralled Abigail. The uncertainties of travel prevented her getting her hopes up, however: “Your last letter has given me more pleasure than any almost since you have been gone, as you hint at a return in a few days-I trust I shall not be disappointed in seeing you by the middle or last of the next week-I allow more than I otherwise should do, from having been disappointed in former calculations.”6

At long last, Thomas came home. In the years following the war, he served on at least four other ships, but his absences did not prevent the young couple from creating a family. Little James Lawrence was the first of five children. Thomas resigned from the navy for good in 1832 and lived happily with his little brood in Brooklyn, New York. He died in 1846 in his 70th year. Abigail outlived him by 28 years. In the end, they were laid to rest side by side in Brooklyn’s glorious Green-Wood Cemetery.

______________________

1 June 1, 1813, Chew Family Papers, Clement Library, University of Michigan.

2 Ibid., May 1, 1814.

3 Ibid., May 7, 1814.

4 Ibid., May 16, 1814.

5 Ibid., September 9, 1814.

6 Ibid., November 4, 1813.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.