Every winter we bundle up against the rain and snow in our heaviest warm weather gear. Have you ever wondered how mariners ever manage to stay dry in similar weather? Today, professional sailors keep a pair of grungy waterproof pants and a hooded jacket hanging in their lockers. Modern technology has given us fabric that both repeals water and breathes, qualities essential for remaining comfortable in the midst of a storm.

In centuries past, however, the standard foul weather gear for naval seamen was some form of woolen jacket or coat and a tarpaulin hat. In a storm, with driving rain or spray, even the stoutest woolen pea jacket or watch coat soon became saturated, and while sodden woolens provide a degree of warmth, their weight and the wetness would soon prove an inconvenience to anyone who had to be active.

In fact, keeping dry was perhaps the biggest challenge for anyone on board a sailing warship. As a sample of what a deep sea sailor might face while sailing in southern latitudes, consider this episode on board the frigate Congress in 1845: “the watch on deck had just been relieved, and were crowding below covered with sleet, stiff with cold, and wading through water ankle-deep to reach their hammocks, there to turn in to sleep in their drenched garments.”1 Herman Melville, no stranger to the miseries of the middle watch, thought one of the reasons that sailors lived short lives was the constant soaking they received while on duty and consequent lack of sleep when they were off.

By the 1830s, a new product entered the scene that promised to put an end to the dampness: India rubber. Called caoutchouc at first, India rubber was a preparation made from the sap of the rubber tree (Siphona elastica), a native of South America. As early as 1824, Scottish textile manufacturer Charles Macintosh produced rubberized waterproof cloth, and the product and technology for making it soon spread to the United States.

Naturally, the US Navy saw the benefit of clothing that promised to keep the wearer dry, and in 1835 Constitution’s purser Henry Etting purchased monkey jackets and pea jackets of India rubber for the ship’s crew. The former cost about $3 and the latter $5, or about half the cost of a woolen garment of similar form.2

Unfortunately, these early rubber coats were not all they were cracked up to be- in fact, they were usually just cracked. Until Charles Goodyear discovered and patented vulcanization in the mid-1840s, India rubber goods had a tendency to became stiff and flaky in cold weather or sticky in hot. The relative instability of the early rubber garments was a definite disadvantage for sailors, who might sail from the frigid waters of the North Atlantic to the baking seas of the equator in the course of a single voyage.

One officer on the Peacock explained the problems with these garments in an amusing 1835 letter:

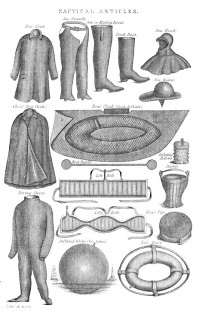

Previous to sailing from New York, most of the officers, taken by the plausible puffs of ‘India Rubber cloth,’ made into various fashions to protect the person from water, supplied themselves with coats, capes, caps, boots and shoes;…

The garments were lauded for being impenetrable to water; the India Rubber was placed between two pieces of thin cloth, either worsted or cotton, and bags made of it, were filled with water and to be seen hung up in the stores for vending the article, and affording ocular demonstrations that they did not let water out; and, as “it is a bad rule that won’t work both ways,” the inference was very plain that it would not let water in.

But on trial the argument has been set aside; the India Rubber garments afford little, or no protection from rain; at least those we purchased do not, and our supplies are from two stores in New York; I state this that the parties may not say one to the other, “you deceive your customers.”

It would amuse you to hear replies made by the officers, when they come below, after a rainy watch, enveloped in folds of India Rubber, some of them hearing no very great unlikeness to the pictures of Don Quixote, seen in the quarto edition of “the adventures” of that valorous knight.

“How stands the India Rubber?”

“Oh! I wish the rascal were here, who sold it to me! I am up to my knees in water, it runs in, but “it won’t run out,” and the caps leak through every seam, the jacket is not worth a groat. I go for a regular tarpaulin and a monkey jacket.”

Thinking that you will not hesitate to inform our brother officers, through the medium of your paper, which is extensively read by them, how we have been mistaken in the qualities of India Rubber cloth, and thus save them useless expense, I have volunteered to write to you for my messmates and shipmates, under the persuasion, you will take the proper steps in the case; and oblige your old friend.

P. S. One of my messmates, distinguished for his benevolence, suggests that, “perhaps we have been cheated in the article.” That is the fact.3

Eventually, the India rubber manufacturers worked out the kinks and could provide truly stable, waterproof clothing that kept the wearer dry and comfortable. The Navy never seemed to give them a second chance in the nineteenth century, however. As late as 1897, the men’s rain clothes were made of “oil cloth” to the “Cape Ann pattern,” which was probably more durable than any rubber garment could be.

3 Army and Navy Chronicle, vol. 1 no. 36 (Washington, DC: B.Homans, 1835), 285.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.