Sailors loved simple comforts. A nap in a corner of the deck, a plug of good tobacco, and the chance to “overhaul” his chest of meager belongings, these were the ne plus ultra of the sailor’s existence. On board a merchant ship, where relations between officers and crew remained friendly, these were pleasures he could indulge in frequently. But on board a warship of the United States Navy, such pleasantries were hard to come by. To be sure, navy tobacco was sweet and mild, if the suppliers followed the letter of their contract. Even on the crowded gun deck of a frigate, a resourceful man could find a snug corner for a snooze. But one thing the service denied him was the permission to keep his clothing and other personal possessions in a sturdy wooden chest.

It is difficult to pinpoint when this restriction began. In 1803, a notation in USS Constitution’s log says, “Bags are to be served out to the Ships Company in Lieu of Chists [sic].”1 This may have been a response to a navy-wide prohibition, or a shipboard regulation enforced by Commodore Edward Preble, a notorious stickler for neatness and discipline generally. This prohibition only applied to the common seamen, however. According to Preble’s “Internal Regulations” for the ship, the petty officers were “allowed to have chests.”2

At any rate, by the War of 1812, U.S. Navy ships had been freed from the clutter of chests. The bags that replaced them presented a new field of challenges and small miseries for the men. Writing almost a generation after the War of 1812, Herman Melville lamented,

“Your clothes are stowed in a large canvas bag, generally painted black, which you can get out of the “rack” only once in the twenty-four hours; and then, during a time of the utmost confusion; among five hundred other bags, with five hundred other sailors diving into each, in the midst of the twilight of the berth-deck. In some measure to obviate this inconvenience, many sailors divide their wardrobes between their

hammocks and their bags; stowing a few frocks and trowsers in the former; so that they can shift at night, if they wish, when the hammocks are piped down. But they gain very little by this.”3

hammocks and their bags; stowing a few frocks and trowsers in the former; so that they can shift at night, if they wish, when the hammocks are piped down. But they gain very little by this.”3

It seems that the unpainted duck linen bags that one frequently sees in museum collections were personal bags used for transporting clothing from ship to shore or shore to ship.4 When a seaman entered a vessel, the purser issued him a painted bag to use for the duration of the cruise, and he relegated his personal bag to the bottom.5 The Navy considered this bag government property, to be returned when a man left the ship. Boston sailmaker Thomas Kendall supplied Constitution with 500 hammocks and 250 bags in 1812 and Navy Agent Amos Binney paid for them just like any other piece of ship’s equipment.6

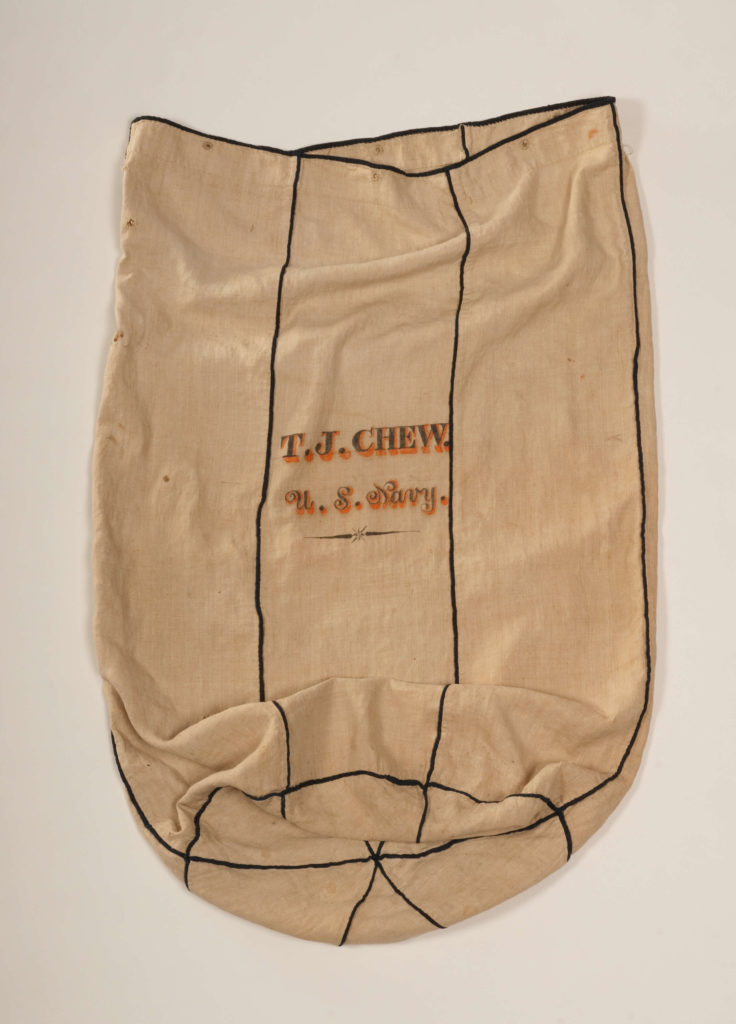

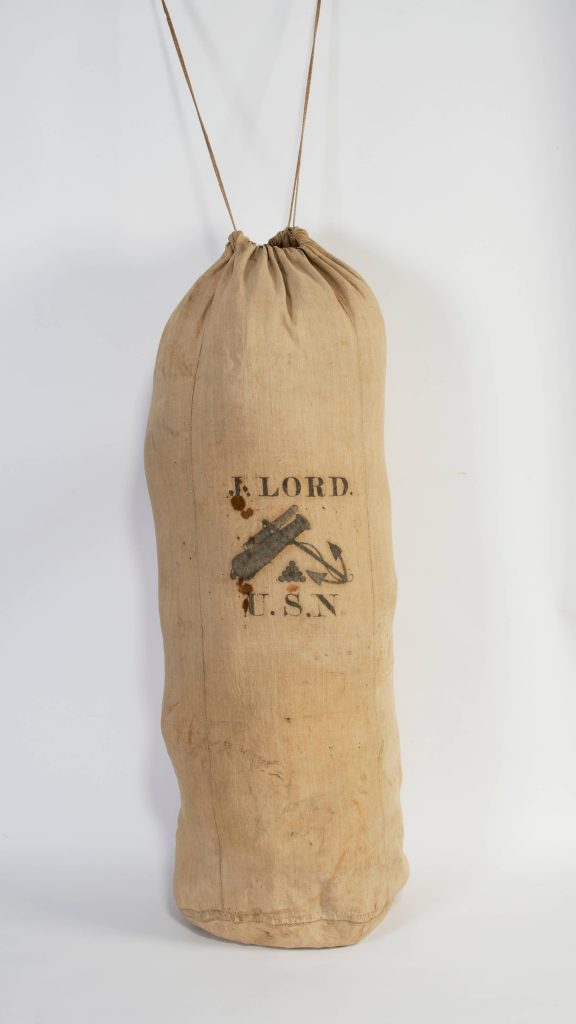

Not a single ship’s issue bag appears to have survived the ravages of frequent scrubbing and surplus auctions, but a small number of unpainted personal bags survive in private and public collections around the country. The extant bags from the first two decades of the nineteenth century exhibit nearly the same dimensions.7 On average, they stand 42 inches high and have a diameter of about 18 inches, making them sufficiently large to carry most of a sailor’s bulky clothing. They are typically made of two, four, or six panels of relatively fine but robust flax linen of 10 or 12-ounce weight. None of these early bags have a fancy ropework lanyard; they all close with a simple hemp draw cord passed through a casing at the bag’s top, or rove through small worked grommets in the tabling. Since the bags belonged to an individual, they usually carry the man’s name or other identifying motif in paint in the center of one of the panels. By the middle of the nineteenth century, gorgeously embroidered bags began to proliferate, and many reside in art museums today, admired as pieces of folk art.

______________________

1 USS Constitution Log, September 2, 1803. National Archives and Records Administration.

2 “Internal Rules and Regulations for the US Frigate Constitution 1803-1804, by Captain Edward Preble, US Navy, Commodore of US Mediterranean Squadron,” in Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers, Vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1941), 35.

3 Herman Melville, White Jacket; or, the World in a Man-of-War (London: Richard Bentley, 1850), 54-55.

4 The term “sea-bag” to refer to a sailor’s clothing bag does not seem to have been in general use before the 1850s. Even then, it is almost always used in a military context as a bag for soldiers to keep their belongings in while on board transports. Not until the 1880s does the word “seabag” appear in sailor’s narratives.

5 This is corroborated, albeit at a later date, by Luce: “Each man is allowed two [bags]; one of white canvas, and one of painted canvas, the former being kept in the latter. They are marked on the side and bottom with the owner’s ‘ship’s number.’” [Textbook of Seamanship…,1891, 298]

6 Amos Binney voucher to Thomas Kendall, 29 Oct. 1812, in Fourth Auditor Settled Accounts, Alphabetical Series, RG 217, Box 39, National Archives and Records Administration. The bags cost 25 cents each to make.

7 A bag that belonged to Purser Thomas J. Chew (resigned 1832) and two bags that belonged to Gunner John Lord (d. 1829) are in the USS Constitution Museum’s Collection.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.