Constitution’s crew, the ones who sailed with Captain Isaac Hull and Commodore William Bainbridge, had more than a few adventures on the high seas. Some of these same men went on to make an epic overland trek that ultimately resulted in one of the U.S. Navy’s greatest victories on the Great Lakes.

By the spring of 1813, the American squadrons building on Lake Ontario and Lake Erie were in desperate need of men. Writing to Secretary of the Navy William Jones on March 5, 1813, Commodore Isaac Chauncey asked for 300 sailors and 200 Marines for the Lake Ontario squadron. In turn, Secretary Jones requested Commodore Bainbridge to open a rendezvous in Boston to recruit men for the lakes. After two weeks, only one man had enlisted (and he promptly deserted).1

Knowing salt-water sailors were averse to serving on fresh, Bainbridge sent two drafts of men from Constitution to Lake Ontario. On May 7, 1813, Secretary Jones praised Bainbridge’s initiative: “The transfer of part of the Crew of the Frigate Constitution to the Service on the Lakes gives me great satisfaction as the nature of the Service required the most prompt and decisive measures to render it effectual.”2 These men had recently returned victorious from the engagement with HMS Java, and many of them were veterans of the Guerriere fight as well. Now that the frigate needed extensive repairs before its next cruise, Bainbridge could afford to dispatch them to the western theater.

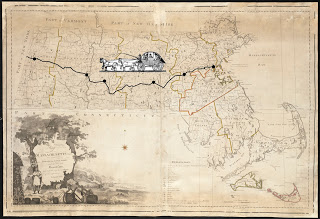

The first detachment of 120 seamen and officers left the Charlestown Navy Yard on April 18, 1813. A second detachment of 50 men departed on April 27. Driven west in four-horse stagecoaches, the sailors made good time on the smooth stage roads. As The Yankee remarked: “These sailors will infuse skill and confidence into the navigation of the Lakes…We much approve transporting our seamen to the interior in carriages, for a sailor does not know how to walk like a soldier; the former makes leeway, while the later marches straight on. We anticipate with pleasure the hearty welcome these fine fellows will meet with…Their fame goes before them, and victory will follow after them.”3

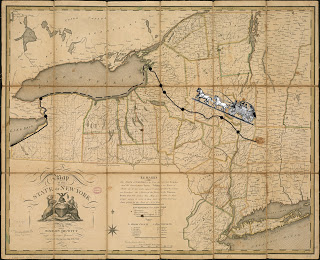

The two groups changed horses (and probably coaches, too) at Framingham, Worcester, Belchertown, Northampton, and Pittsfield. From Pittsfield they steered for Albany, New York, and then on to Amsterdam and Utica. The second detachment lost two men on the road. Sailing Master John Nichols died on May 10 at Lorraine, New York, and Seaman John Harvey died on the 12th at Redfield, about 15 miles south of Sackets Harbor.4

We don’t have anecdotes of the trek in the words of any of Constitution’s crew, but Seaman Ned Myers made a similar march from New York City to Lake Champlain. He described the adventures of the party:

“Towards the end of the season, our boat, with several others, was lying abreast of the Yard, when orders came off to meet the Yard Commander, Captain Chauncey, on the wharf. Here this officer addressed us, and said he was about to proceed to Lake Ontario, to take command, and asking who would volunteer to go with him. This was agreeable news to us, for we hated the gun-boats, and would go anywhere to be quit of them. Every man and boy volunteered. We got twenty-four hours’ liberty, with a few dollars in money, and when this scrape was over every man returned, and we embarked in a sloop for Albany. Our draft contained near 140 men….On reaching Albany, we paid a visit to the governor, gave him three cheers, got some good cheer in return, and were all stowed in wagons, a mess in each, before his door. We now took to our land tacks, and a merry time we had of it. Our first day’s run was to a place called Schenectady, and here the officers found an empty house, and berthed us all together, fastening the doors. This did not suit our notions of a land cruise, and we began to grumble. There was a regular hard horse of a boatswain’s-mate with us, of the name of McNally. This man had been in the service a long time, and was a thorough man-of-war’s man. He had collected twenty-four of us, whom he called his ‘disciples,’ and shamed am I to say, I was one. McNally called all hands on the upper deck, as he called it, that is to say, in the garret, and made us a speech. He said this was no way to treat volunteers, and proposed that we should ‘unship the awning.’ We rigged pries, and, first singing out ‘Stand from under,’ hove one half of the roof into the street, and the other into the garden. We then gave three cheers at our success. The officers now came down, and gave us a lecture; but made out so good a case, that they let us run till morning, when every soul was back, and mustered in the wagons. In this way we went through the country, cracking our jokes, laughing, and noting all oddities that crossed our course. I believe we were ten or twelve days working our way through the state to Oswego. At Onondago Lake we got into boats, and did better than in the wagons. At a village on the lake shore the people were very bitter against us, and we had some difficulty. The word went among us they were Scotch, from the Canadas, but of this I know nothing. We heard in the morning, however, that most of our officers were in limbo, and we crossed and marched up a hill, intending to burn, sink, and destroy, if they were not liberated. Mischief was prevented by the appearance of Mr. Mix [sailing master commanding the detachment], with the other gentlemen, and we pushed off without coming to blows.

“It came on to rain very hard, and we fetched up at a solitary house in the woods, and tried to get quarters. These were denied us, and we were told to shift for ourselves. This we did in a large barn, where we made good stowage until morning. In the night we caught the owner coming about with a lantern to set fire to the barn, and we carried him down to a boat, and lashed him there until morning, letting the rain wash all the combustible matter out of him. That day we reached Oswego Falls, where a party of us were stationed some time, running boats over, and carrying stores across the portage.”5

The first detachment reported for duty at Lake Ontario on April 29. The second arrived around May 12. The final disposition of all the officers and men is unknown, however many were portioned out to the Lake Ontario squadron. On July 10, 1813, Chauncey ordered Midshipman Dulany Forrest to take 60 men from Sackets Harbor to join Oliver Hazard Perry’s squadron on Lake Erie.6

The schooner Pert landed the men at the mouth of the Niagara River. They marched to Black Rock with orders not to stop in Buffalo, but to “push on as fast as possible.” From Black Rock they followed the lakeshore to Presqu’ile. The men walked and wagons followed with their baggage. The draft reached Erie on July 23 or 28. Because Constitution’s muster rolls for 1813 have gone missing, it is difficult to create a comprehensive list of the men who were drafted for the Lakes.

There is no doubt, however, that the drafts from Constitution proved decisive in the pivotal Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. The Albany newspaper expected them to “entwinein the chaplets that adorn their brows, some sprigs of Canadian laurel,” while the Boston papers were sure they would “act over again the conquests of the Guerriere and the Java.”

1 G. Martin (Ret.), “The Constitution Connection,” The Journal of Erie Studies, vol. 17, no. 2 (Fall 1988), 39-46.

2 William Jones to William Bainbridge, May 7, 1813, in Secretary of the Navy Letters to Commandants and Navy Agents, 1808-1865, M441, NARA.

3 The Yankee, April 23, 1813.

4 The sequence of the march is based on the settled receipts of Sailing Master John Nichols, Settled Accounts of Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, Numerical Series, RG 217, No. 208, NARA.

5 James Fenimore Cooper, ed., Ned Myers; or, A Life Before the Mast (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1843), 47-48.

6 Isaac Chauncey to Dulany Forrest, Accounts of Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, Numerical Series, RG 217, No. 3739, NARA.

7 Albany Argus, April 23, 1813, and Baltimore Patriot, 26 April 1813.

8 Quoted in Richard J. Cox, “An Eyewitness Account of the Battle of Lake Erie,” Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute (Feb. 1978), 71.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.