The lower decks of a ship of war were dark, dank places. Even on a frigate with a single gundeck, little natural light filtered down to the crew’s living quarters on the berth deck. Below that, the orlop, hold, and the rabbit’s warren of storage rooms were swathed in perpetual gloom. While tin lanterns charged with a single tallow or spermaceti candle might provide a narrow circle of light, their feeble illumination did little to alleviate the dark and dancing shadows.

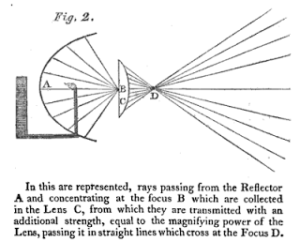

Oil lamps provided a brighter, steadier light. In 1781, Swiss physicist Aimé Argand invented a new lamp that used a hollow cylindrical wick. Combined with a glass chimney, the steady airflow inside and outside the wick provided a strong light with a minimum amount of flickering. By the turn of the century, Argand lamps were in general use throughout Europe and America.

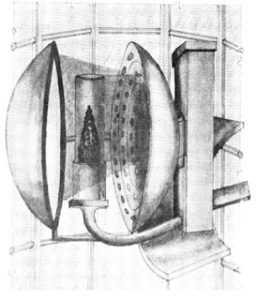

We don’t know who first used Argand lamps in a maritime context, but in 1808 a former Massachusetts sea captain named Winslow Lewis patented his “Binnacle Illuminator.” The invention combined the clear light of an Argand-style lamp with a series of parabolic reflectors that could simultaneously light a binnacle on deck (a box-like structure that housed the ship’s compass) and the cabin below. Best of all, the arrangement used only “one half the oil that the Binnacle alone formerly consumed.”1

At the same time, Lewis began tinkering with convex lenses that could both magnify and focus a beam of light. He sold them as “patent illuminators, or sky lights for shipping.” Set into deck planking, they let light below and were guaranteed not to leak, break, or “be injured by the common traffic of the deck.”2

Soon, he combined his reflector, lamp, and lens to create a powerful new lighting device. In 1811, he exchanged the old style lamp in Boston Lighthouse for his new reflecting lamp. The difference was dramatic. The old light could be seen five or six leagues at sea, but Lewis’s penetrated the night to the distance of 12 leagues (a league was three nautical miles). The old lamps were horribly inefficient, requiring 31 gallons of whale oil per week. The new cleaner-burning lamps needed only nine.3

Thanks to the lamp’s impressive qualities and some friends in high places, Congress passed an act in March 1812 that gave Winslow Lewis a virtual monopoly to supply all United States lighthouses with his “reflecting and magnifying lanterns.” By the end of 1812, Lewis had received at least $16,000 from the government for installing his lamps and reflectors.

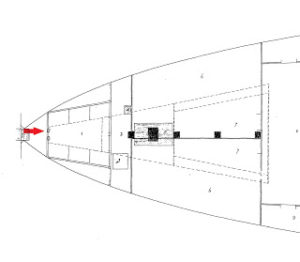

Despite his success and busy schedule, Lewis continued to supply shipping with his lenses and reflectors. Constitution returned to Boston after her successful engagement with HMS Java, in February 1813, but spent the rest of the year undergoing major repairs. Part of the work included installing some of Lewis’ patent devices. In September, Lewis submitted a bill for five “9 Inch Patent Convex Lens’s [sic],” one nine-inch “Patent Illuminator & Reflector,” “A Copper Lanthorn with 3 lights,” a “large Copper Lamp & oil dish,” a dozen “Glass Lamp Tubes,” and six dozen lamp wicks, all for the substantial price of $116.50.4

What was all this used for? The lenses may have been fitted in the light boxes in the magazine’s filling room, providing illumination without the risk of igniting stray grains of gunpowder. It is also possible that these were installed in the spar deck to light the cabin or gun deck below. The large copper lantern might have been used for signaling or as an anchor light. The crew might have kept the other lamp and “illuminator & reflector” handy, ready to be used when they required a strong light.

Whatever the utility of his patented inventions, Winslow Lewis’ devices lighted mariners home for the next 41 years. Even after French scientist Augustin Fresnel invented his vastly superior lighthouse lens in 1823, bureaucratic ineptitude (some said corruption) kept them out of US lighthouses until 1853.

1 New England Palladium, (Boston), 7 Feb. 1809.

2 New England Palladium, (Boston), 15 July 1808.

3 The Balance, and State Journal, (Albany, NY), 7 July, 1811.

4 Amos Binney voucher to Winslow Lewis & Co., 16 Sept. 1813, in Fourth Auditor of the Treasury Accounts, RG 217, Box 38, NARA.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.