Open any book about naval warfare in the age of sail, and you’ll undoubtedly find frequent reference to boys serving on board ship. The most alluring of these stories inevitably hinges on the fact that in some instances, boys were used to carry gunpowder cartridges to the guns in battle. Colloquially called “powder monkeys,” these boys supposedly formed the most important link in a human chain that stretched from the powder magazines to the men who actually loaded and fired the guns.1

There are a number of problems with this often repeated scenario. While there are many examples of young boys serving in this capacity in the British Royal Navy during the period, the evidence for the U.S. Navy is less clear cut. For one, the Royal Navy suffered a considerable manpower shortage by the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and captains scrambled to find manpower (or boypower) wherever they could. American warships, on the other hand, tended to have a higher percentage of experienced seamen among their crews, and this meant that there were fewer boys in general.

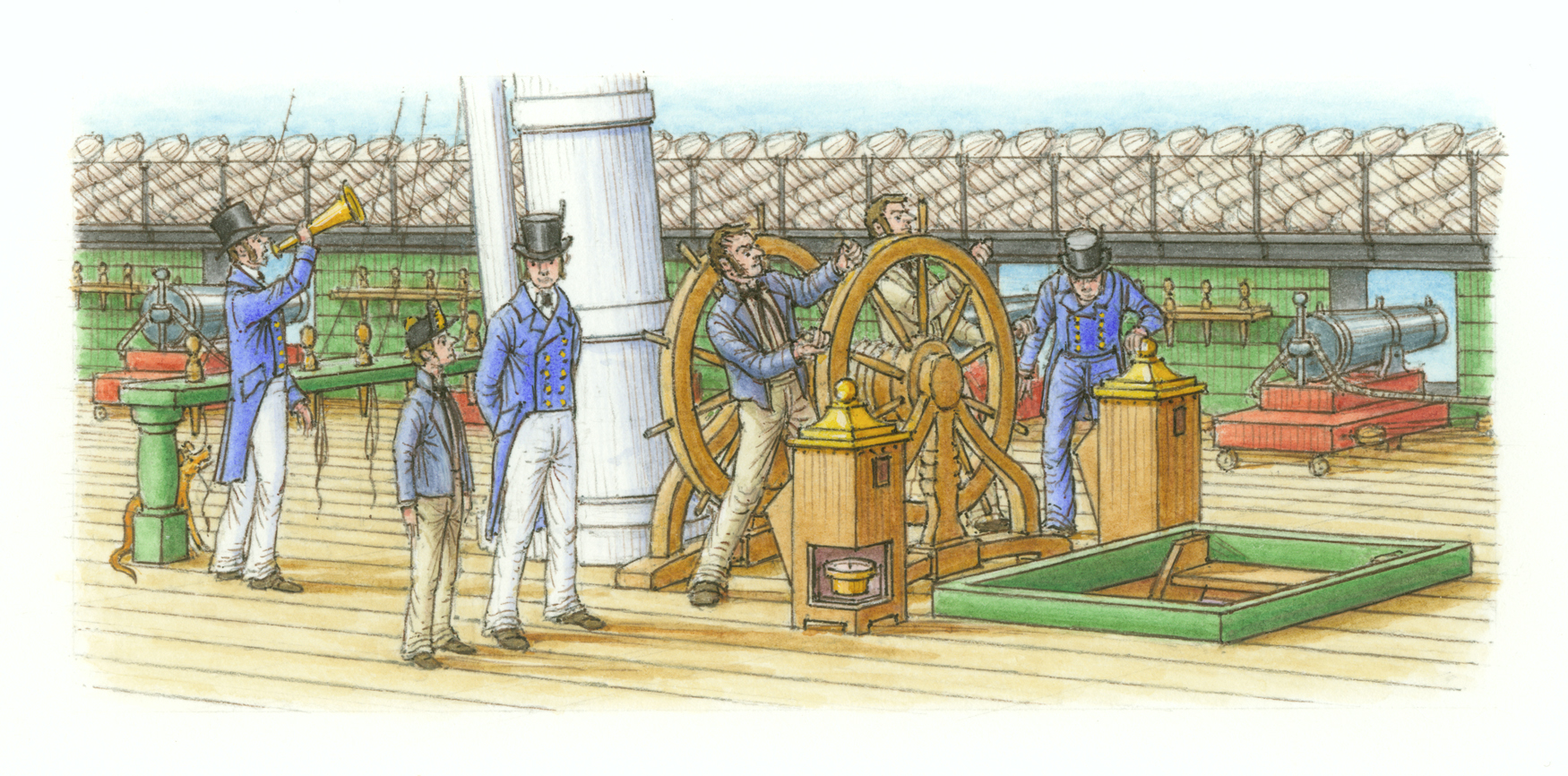

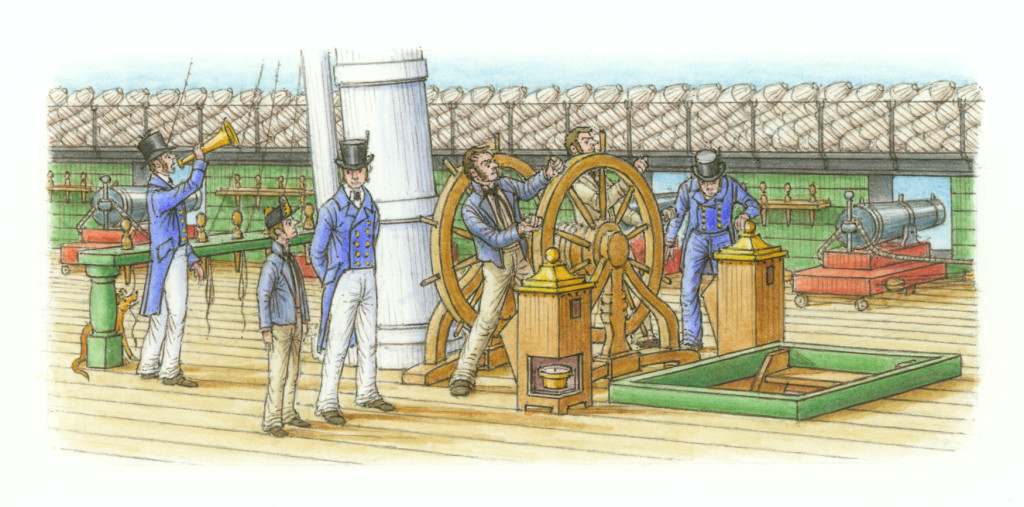

Constitution is a fine case in point. Luckily, a number of watch and quarter bills from the 1812 period survive, allowing us to see who filled the important “powder passing” roll. One created under the efficient eye of William Bainbridge in late 1812 reveals that eight ordinary seamen, two able seamen, 11 boys, and four men of unknown rate passed powder to the guns. In 1814, 14 ordinary seamen, two able seamen, and 11 boys performed the same duties.

On the face of things, it would appear that the powder passing duties were pretty evenly divided between seamen and boys. The problem is, sailors rated as boys were not always boys. The enlisted rating system in the U.S. Navy could be a bit confusing. When they joined a ship, sailors might be rated able seamen, ordinary seamen, or boys. This last rating had nothing to do with age (although there were plenty of boys who were younger than 18), but rather experience. The Royal Navy called these people “landsmen,” a far more descriptive term for those who had little shipboard experience.

The youngest members of the crew served as servants to officers and performed any number of menial tasks on board. Nine-year-old David Debias, for instance, served Master’s Mate Nathaniel Leighton. Shipboard regulations typically placed boys under the supervision of a petty officer. The 1809 regulations for Constitution say, “The master at arms is to keep a list of the boys and of their clothes & to have an especial eye to their conduct, cleanliness and behavior. Every morning at 7 o’clock he is to take care that they are assembled upon the quarter deck attended by himself or one of his corporals and after having been examined report them to the officer of the watch whom orders he is to receive to dismiss them… the commissioned warrant & petty officers, having boys attending on them as servants are expected to take care that they are properly clothed and kept clean and neat.”

1 Allowing the “powder monkeys” to run from gun deck or spar deck to the magazine and back again would have created chaos in battle. To alleviate confusion, a chain or “bucket brigade” passed the filled “pass boxes” from the magazine scuttle across the berth deck and up ladders to the gun deck or spar deck. The “powder monkeys” received the boxes at the hatch, and only then scurried to their respective guns. After delivering a cartridge to the loaders, they brought the empty pass box back to the hatch and received another full box.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.