Every year on December 7, the United States pauses to remember the great loss of life sustained and the great feats of heroism and valor performed by members of the U.S. Armed Forces stationed at Pearl Harbor during the attack in 1941. When looking at the roster of ships in Pearl Harbor on that “date which will live in infamy,” one finds familiar names of former officers of USS Constitution, including Hull and Preble. A deeper look uncovers other ships with fascinating stories named after lesser known men with connections to “Old Ironsides.” USS Ward is one of these.

USS Ward’s role in the response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor is well documented. Ward, under the command of Lieutenant Commander William W. Outerbridge, was part of the Inshore Patrol outside Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941. At 3:42 AM, the minesweeper USS Condor spotted what appeared to be the periscope of a submarine in an area outside the harbor entrance, where submarines were prohibited from operating submerged, and notified Ward. For the next hour and half, the destroyer searched for the submarine without success. At 6:37 AM, the submarine was spotted again, this time following the repair ship USS Antares as it steered for Pearl Harbor with two target barges in tow. Ward was notified again, and this time the destroyer’s crew spotted the submarine and opened fire at 6:45 AM. According to Outerbridge’s after action report:

“The shot from No. 1 gun missed…The shot from No. 3 gun fired at a range of 560 yards or less struck the submarine at the waterline which was the junction of the hull and coning tower. Damage was seen by several members of he crew. This was a square positive hit …The projectile was not seen to explode outside the hull of the submarine. There was no splash of any size that might results from an explosion or ricochet… Immediately after being hit the submarine appeared to slow and sink. She ran into our depth charge barrage and appeared to be directly over an exploding charge.”1

Between 6:45 and 6:53 AM, a report of the attack was sent to the 14th Naval District, stating: “We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges on a submarine operating in defensive sea areas.”2 This report, sent more than an hour before waves of Japanese carrier planes appeared over Oahu, reached Admiral Bloch’s staff by 7:15 AM. Admiral Bloch later testified that “in view of numerous previous reports of submarine contacts…[his] reaction was that the Ward had probably been mistaken.”3 In the opinion of the Joint Congressional Committee that investigated the attack in 1946:

“The reported sighting of a submarine periscope…in close proximity to Pearl Harbor, even though not verified, should have put the entire Navy command on the qui vive and when at 6:40 a.m. the presence of a submarine was definitely established, the entire Navy command should have been on a full alert…The evidence does not reflect that the sighting and sinking of a submarine, particularly in close proximity to Pearl Harbor, was of such frequent occurrence as to justify the failure to attach significance to the events of the morning of December 7.”4

In his after action report to the Commandant of the 14th Naval District, the Commander of Destroyer Division 80, Outerbridge’s Commanding Officer, stated that “the quick decision and prompt effective action of the Commanding Officer and crew of the Ward are considered highly commendable” and he “strongly recommended [Outerbridge] for the award of the Navy Cross,” the second highest award that can be presented to a member of the United States Navy.5

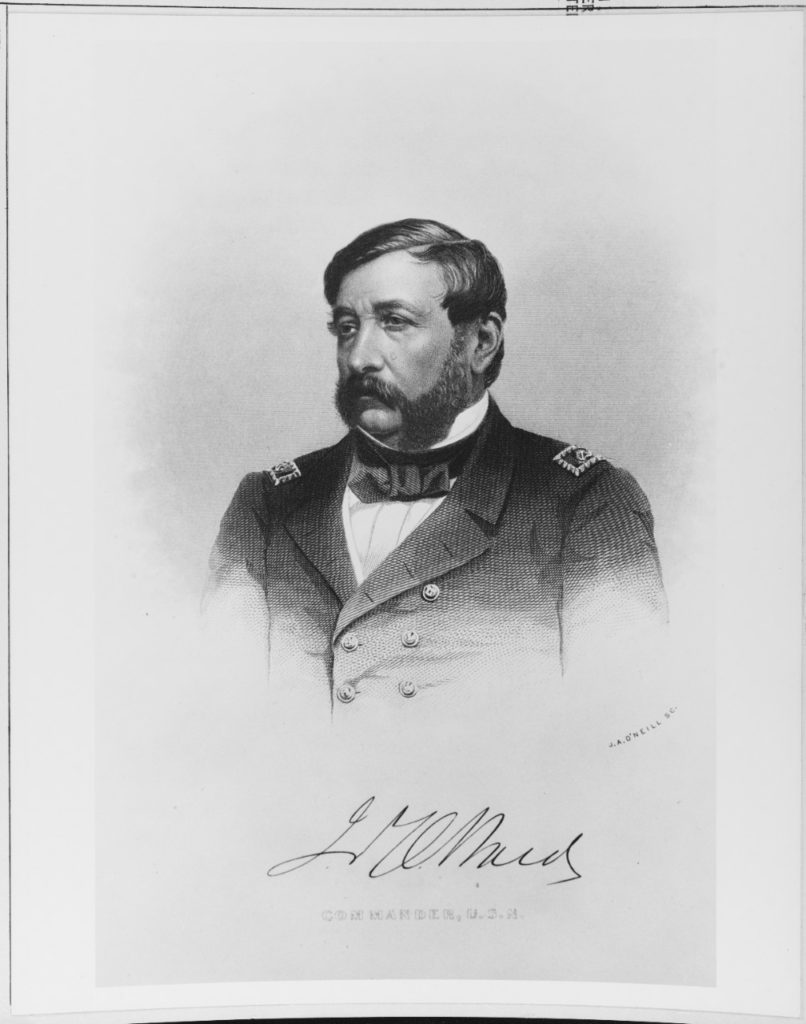

USS Ward (DD-139) was named in honor of Commander James Harmon Ward, the first U.S. Navy officer killed during the American Civil War. Ward was born in 1806 in Hartford, Connecticut, and graduated from the American Literary Scientific and Military Academy in Norwich, Vermont, in 1823. That same year, he was appointed midshipman and joined USS Constitution’s crew on October 17, 1824 for a four-year Mediterranean cruise under the command of Captain Daniel Todd Patterson.6 A watch and quarter bill from 1825 shows Ward quartered with three other midshipmen in the 1st Division on the gun deck under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Wyman.7 When mooring and unmooring, Ward was in command of a group of seamen taking the nippers off the cable and, when reefing and hoisting sail, he was “to see clear Main Topsail clewlines, buntlines, reef tackles, & Main Top Gallant sheets.”8 After being detached from “Old Ironsides” on July 31, 1828, Ward took a one-year leave of absence to pursue scientific studies. When he returned to the service in 1829, he served in the Mediterranean Squadron again, “and then saw service off the coast of Africa…and in the West Indies.”9

Ward went on to teach ordnance and gunnery at the Naval School in Philadelphia. After 1845, he served as the Executive Officer of the Naval Academy, in addition to teaching gunnery and steam engineering.10 He also authored a number of important professional books and treatises, including An Elementary Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery, A Manual of Naval Tactics (1859) and Steam for the Millions (1860). Following his service at the Academy, Ward held a number command positions, including aboard USS Cumberland, USS Vixen, and USS Jamestown. After the American Civil War broke out, Ward commanded “a ‘flying squadron’ [later known as the Potomac Flotilla]… in the Chesapeake Bay for use against Confederate naval and land forces threatening that area south of the Union capital.”11 During action on June 27, 1861, a bullet struck Ward in the abdomen while his ship, USS Thomas Freeborn, was providing gunfire support to Union forces ashore, and he “fell to the deck, mortally wounded.”12

USS Ward, a Wickes-class destroyer sponsored by his great-granddaughter, Dorothy Hall Ward, was launched on June 1, 1918 and commissioned on July 24, 1918 under Commander Milton S. Davis. Over the next three years, Ward served in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, participating in annual fleet training maneuvers, making port visits, serving as a navigational aid, and providing lifeguard services for transatlantic flights. The ship was decommissioned on July 21, 1921 and placed in reserve on “Red Lead Row” in San Diego until rising tensions with the Axis Powers required its return to service on January 15, 1941.

After refitting, Ward was dispatched to Pearl Harbor to join Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 80, part of the 14th Naval District headquartered at Pearl Harbor, to provide anti-submarine patrol off the harbor’s entrance channel. In the wake of a November 27 war warning from Washington, D.C., Ward and the other ships of the Inshore Patrol were ordered “to depth-charge suspicious submarine contacts” operating in the defensive sea areas. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the ship continued service as part of the Inshore Patrol until ordered to Bremerton, Washington in 1942 “for conversion to a high-speed transport at the Puget Sound Navy Yard.”13

Now designated APD-16, Ward set sail for Espiritu Santo and the war in the Pacific in February 1943 to join the Seventh Fleet. Over the next year and a half, the ship transported Marines, soldiers, and Seabees to various islands, escorted larger transports in convoy, and provided anti-submarine and anti-aircraft patrol in support of operations off New Guinea and in the Philippines. On the morning of December 7, 1944, Ward was on patrol off Leyte Island in the Philippines in company with USS Mahan (DD-364) when a flock of nine Japanese planes attacked the two ships. One of the Japanese planes struck by Ward’s anti-aircraft fire crashed into the ship, causing uncontrollable fires below decks. The plane penetrated the hull, entering one of the boiler rooms and a lower troop space, before one of the plane’s engines exited through the starboard side. Ward received aid from several nearby ships, including USS O’Brien (DD-725), under the command of Lieutenant Commander William W. Outerbridge, the same officer who commanded Ward off Pearl Harbor. Despite their best efforts to fight the blaze, the fires were too fierce and the crew abandoned ship. The Task Group commander ordered Outerbridge to sink Ward with gunfire. At 11:30 AM on December 7, 1944, three years after the ship’s valiant defense of the approaches to Pearl Harbor, Ward sank in Ormoc Bay off Leyte.14

1 Naval History and Heritage Command, “USS Ward, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack.” Accessed December 13, 2012. https://www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/pearl/ph97.htm.

2 Ibid.

3 U.S. Congress. Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack. Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack: Report of the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack.79th Cong. Laguna Hills, CA: Aegean Park Press, 1994 (Orig. pub. 1946), 139.

4 Ibid.

5 “Commander Destroyer Division EIGHTY, Report for Pearl Harbor Attack.” Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed March 3, 2013. https://www.history.navy.mil/docs/wwii/pearl/ph9.htm. Outerbridge did receive the Navy Cross for his actions that morning.

6 It should also be noted that USS Patterson, named in Captain Patteron’s honor, was also in Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941. Patterson’s Commanding Officer claims in his after action report to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander in Chief, US Fleet, that Patterson’s number 2 gun shot down one Japanese plane during the attack “based on the absence of any burst nearby at this instant and the belief that the sudden and complete disintegration of this plane could not have been cause by a hit from any small caliber gun. Patterson got underway at 9:00 am. Naval History and Heritage Command. “Patterson.” Dictionary of Naval Fighting Ships. Accessed January 29, 2013. https://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/p3/patterson-ii.htm.

7 USS Constitution Watch and Quarter Bill, 1825, Daniel Todd Patterson Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress.

8 Ibid.

9 Naval History and Heritage Command. “Ward.” Dictionary of Naval Fighting Ships. Accessed December 13, 2012. https://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/w3/ward.htm.

10 The rank of Executive Officer for the Naval Academy was renamed Commandant of Midshipmen. Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

The Author(s)

Brian Miskell

Administrative Coordinator, USS Constitution Museum

Brian Miskell is the Administrative Coordinator at the USS Constitution Museum.