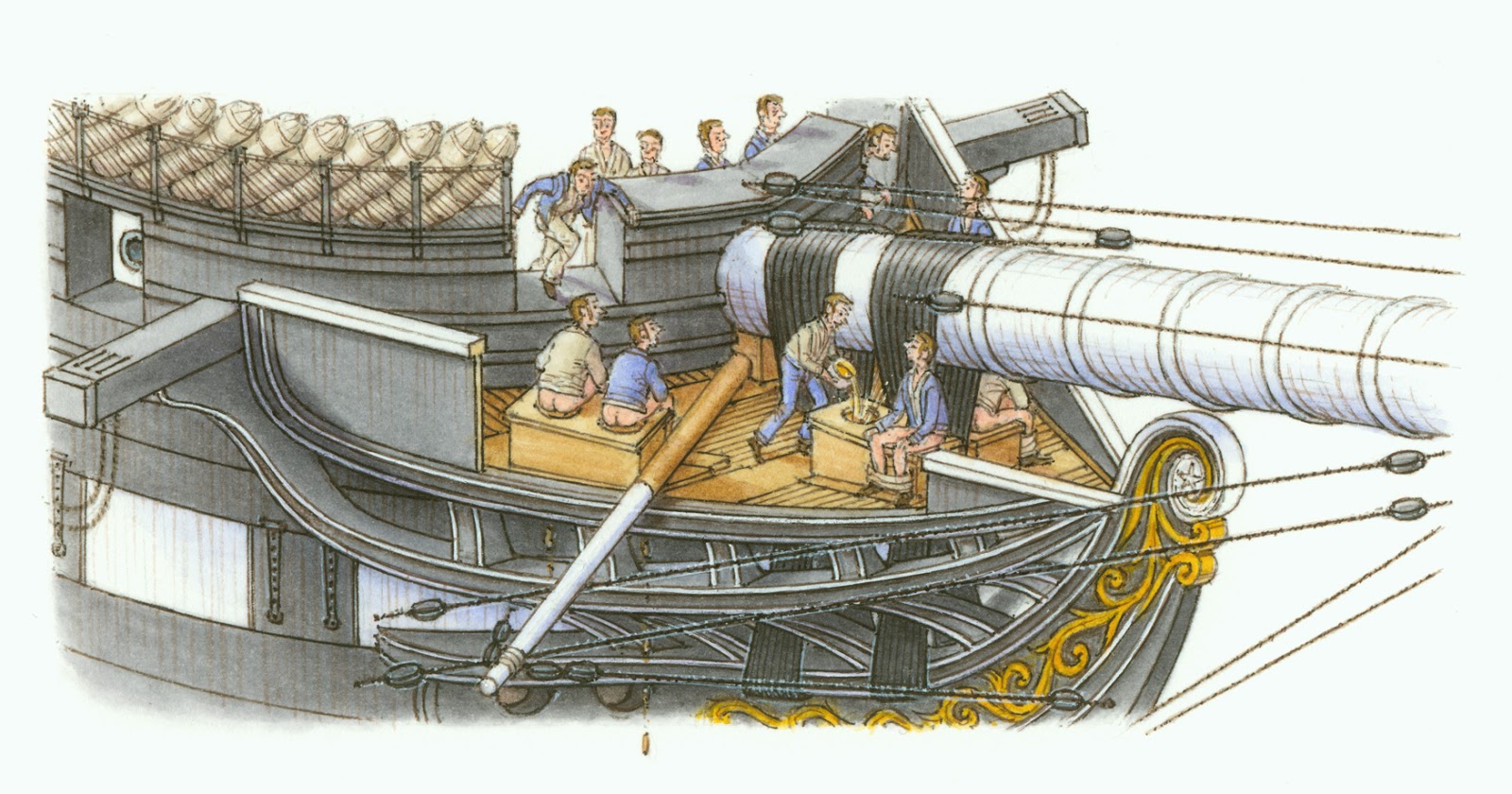

When nature called, USS Constitution’s sailors had few facilities at their disposal. For the common seamen and Marines, the primitive toilet facilities of the head beckoned. Consisting of four or six holes cut in a plank overhanging the water in the bow of the ship, the heads provided little in the way of privacy or comfort. In cold weather or rough seas, a trip forward must have been an unpleasant, if not downright dangerous, undertaking.

The ship’s officers and the sick confined to sick bay used the best facilities in the ship. The captain had the cushiest arrangements. His private privy was located in one of the quarter galleries, the lavishly decorated projections overhanging the ship’s stern quarters to port and starboard. Some British ships of the period had flushing water closets rigged in the quarter galleries, and it is possible Constitution did too.1

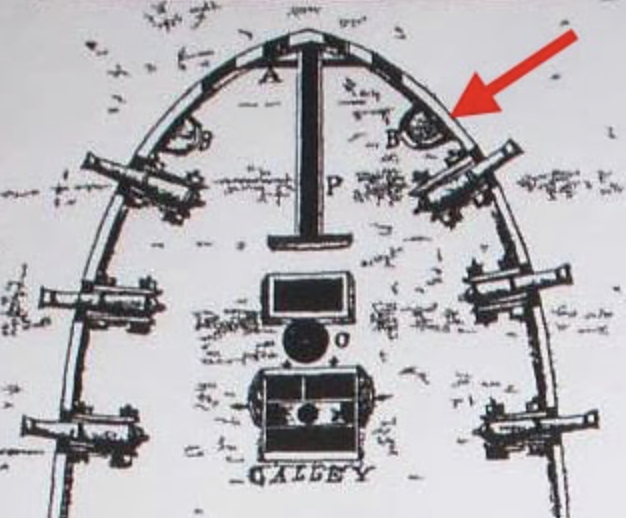

The wardroom officers likely kept chamber pots in their cabins as well, but they also had recourse to slightly better toilet facilities than the rest of the crew. Frigates typically carried two “round houses” forward on the gun deck. These structures, consisting of wooden half-cylindrical screens erected against the ship’s side, provided a sheltered place to do one’s business. Though more comfortable than the head, using them could still be dangerous, as suggested by an incident on board HMS Lapwing in 1798:

“The Purser went into the weather round House, about this time which is fixed in the Galley, on the Ships Bows. While he was on the Seat, a mass of wind was forced by a wave up the Galley of the round House. that its violence breaking against the naked Posterior of the Purser, it so lacerated his parts & Aunus, that he was oblidged to get medical assistance, as a quantity of wind had forced a passage into his Belly.”2

Before Constitution’s battle with HMS Levant and HMS Cyane in 1815, the ship’s crew removed the round houses to “afford room to work the forward deck guns in action.” According to Chaplain Assheton Humphreys, the removal of the “spice boxes,” as the crew called them, forced the officers “to make the chains [the narrow platforms on the side of the ship to which the shrouds were attached] the scene of their profane rites,” or stealthily slip into the quarter galleries.

The British officers, used to ships “abounding in every convenience that could be desirable for the comfort of a cruising vessel,” found the spectacle of officers doing in the open air what they usually did in private disgusting. Captain Gordon Thomas Falcon, late of HMS Cyane, remarked to Lieutenant Henry Ballard “in a tone truly contemptuous that ‘a British Officer would think it derogatory to be found in the chains in the obscene manner in which he perceived the Americans visited them.’ To this impertinent remark the following pertinent answer was made and it had the effect of silencing the gentleman upon such subjects for the future ‘Why, Sir, we know that these things are mere matter of opinion and our reputation not at all affected by it provided our discipline otherwise is such as will do ourselves credit and our country justice, and when her reputation is at stake we are particular in little else, provided our guns tell well, and you can be a competent judge of how far that end has been attained.’”3

The sailors in sick bay, too ill to clamber up to the head, had use of one of the roundhouses and also tin or pewter bedpans and “pewter urinals.”4

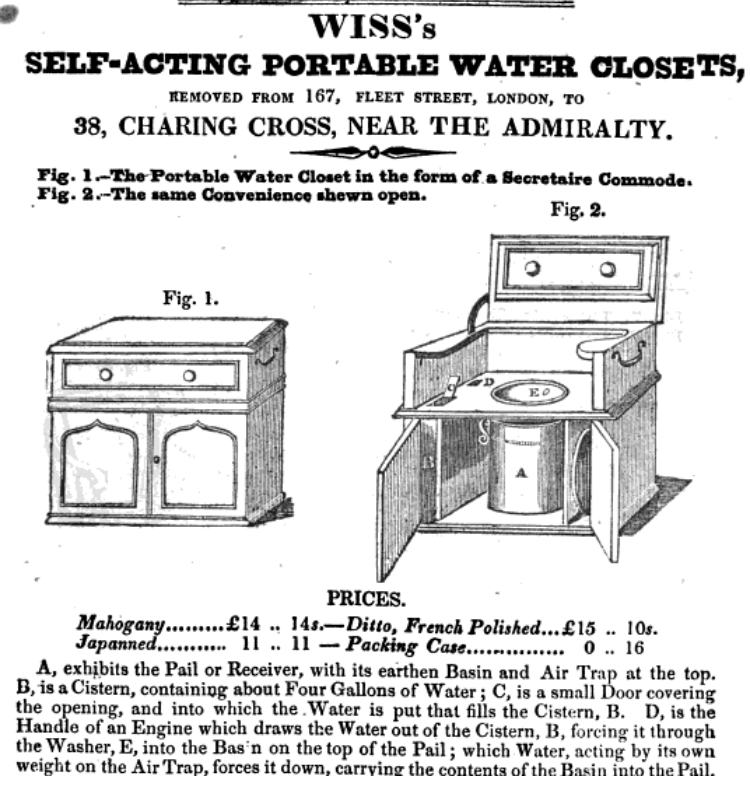

So stood the facilities on board Constitution at the end of the War of 1812. All of these remained virtually unchanged for the next 20 years, until the ship finally received the latest in sanitary technology. In the summer of 1834, the Navy Board of Commissioners agreed to Captain Jesse Duncan Elliott’s request to install “portable patent water closets” in Constitution’s sick bay. These were designed and marketed by the incredibly aptly named Henry Philpott, who would make them of “cherry, maple, or and other good hard wood.” Such comfort didn’t come cheaply, however; they cost $24.25 each.5

The 1832 Boston directory lists Philpot(t) as a “plumber” at 3 Court St., but we’ve yet to locate a description of his patent toilet. If it was like other early water closets, it probably featured a cistern or tank to hold water and some sort of receptacle for waste. In fact, it probably looked and functioned a lot like Mr. Wiss’s “self-acting portable water closets” advertised in 1831.6 Nevertheless, it would be years before the sailors of Constitution enjoyed this sort of luxury.

1 In 1813, T. and R. Howe of Boston charged the U.S. Navy for “casting pipe for Nessery [sic, necessary]” which may have referred to the quarter gallery privy. [T and R Howe receipt, May 14, 1813, in Fourth Auditor Settled Accounts, Alphabetical Series, RG 217, Box 39, National Archives and Records Administration.]

2 Aaron Thomas, “The Caribbean Journal of a Royal Navy Seaman,” University of Miami Libraries Special Collections Division

3 Tyrone G. Martin, ed., The USS Constitution’s Finest Fight, 1815: The Journal of Acting Chaplain Assheton Humphreys, US Navy, (Mount Pleasant, SC: Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 2000), 35-36.

4 Andrew Greene receipt, July 13, 1813, in Fourth Auditor Settled Accounts, Alphabetical Series, RG 217, Box 39, National Archives and Records Administration.

5] Isaac Chauncey to Jesse Duncan Elliott, July 19, 1834, in Boston Navy Yard, Letters and Circulars Received from Board of Navy Commissioners 1825-1842, RG 181, National Archives and Records Administration, Waltham, MA.

6 The Quarterly Literary Advertiser (London, Jan. 1831).

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.