In the early nineteenth century, the terms naval officer and gentleman were synonymous. Acting like a gentleman was one thing, but he had to also live like one. Snowy linen shirts, clean trousers, and polished boots were only one part of the equation. A man’s living quarters had to reflect his status as well.

A document sent to Commodore Edward Preble while outfitting Constitution in 1803 gives us a glimpse of the sort of surroundings a high-ranking naval officer enjoyed while engaged in active service.1

We can divide the items in the list into three categories; items for table service, items for food preparation, and furnishings.

An officer of Preble’s standing expected to entertain his own officers, politicians, and foreign dignitaries with style and hospitality. An elegant table setting did much to reinforce his own importance and did honor to the flag. Judging from the number of chairs and place settings supplied, the commodore could expect as many as a dozen guests at a time.

First and foremost, guests had to sit a clean table. Two pewter wash “basons” and two pitchers encouraged pre-meal hand washing. Two dozen table cloths and two dozen napkins presented a snowy array of linen to the visitor. Beneath the cloths were laid rectangles of green baize to protect the tables’ surface.

For serving tea and coffee, the cabin stewards had two tea kettles, a set of tea china (as well as a dozen “common cups & saucers”), a dozen sterling silver teaspoons and a half dozen silver plated.2

They passed condiments around using the half dozen “salts,” butter boats, and the set of castors.

When it came to preparing food for the captain, Cook James Brumade and the cabin steward had a kitchen’s worth of pots, pans and instruments at their disposal.3 Two iron pots (with pot hooks), a griddle, and three frying pans let them cook up just about anything the Commodore could desire. There were 12 stew and sauce pans, and even a “tin kitchen,” a shiny reflector for roasting meat. An iron ladle, a dozen skewers, a skimmer, and pair of “tormentors,” or large flesh forks, helped with turning and serving the dishes. A cheese toaster, á la Patrick O’Brian’s Killick and Jack Aubrey, provided a hot snack.

The cooks could bake a mean pie or cake in the iron Dutch oven. A dozen tin “patty pans” and two tin pudding pans gave them forms for doing it. Preble and his guest could never have their cakes or puddings without tea and coffee. Besides the assorted tin canisters for holding leaves and beans and sugar, the cabin outfit included a coffee mill. One “filtering Stone,” a porous piece of rock long used to remove impurities from drinking water, removed some of the bad odor from the ship’s water.

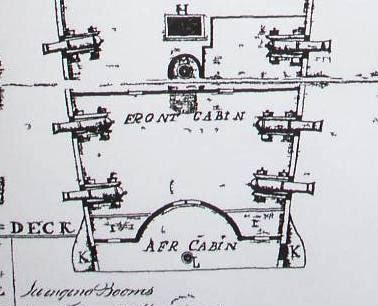

The captain’s two cabins might have lacked the interior finishes of an expensive house ashore, but at least the furnishings enlivened the Spartan surroundings. First of all, it was brilliantly lit. Besides the stern gallery windows that flooded the after cabin with dancing sunlight and the light that came in through the gun ports in the forward cabin, Preble’s space was filled with artificial lighting devices. Six candlesticks probably graced the dining table, but he could also fire up four “patent lamps” and one “globe lamp”, which very well may have been the new Argand oil lamps capable of producing as much light as nine wax candles each. Two pairs of snuffers and tongs kept the wicks burning well and made them easy to light by carrying a coal from the cabin stove.

If Preble wanted to block out the sunlight while he retired to his “cott,” he could draw a set of “stern curtains” across the windows. Visitors might be asked to sit on one of two “setters with squabs,” that is, settees or couches with cushions.4 A small carpet gave Preble something to sink his toes into, and if he wanted to check the set of his cravat or the arrangement of his comb over before venturing onto the quarterdeck, he had a looking glass at his disposal.

Some officers must have considered life at sea a hardship, at least as far as creature comforts were concerned. And yet, as this list of cabin furniture for Constitution demonstrates, they had most of the essential comforts of home at their disposal. Many a common sailor would have killed for similar quarters.

1 “List of Cabin furniture allowed the Frigate Constitution,” 5 July 1803, in Letters to Officers of Ships of War, M149, vol. 6, NARA.

2 The 1818 Rules, Regulations and Instructions for the Naval Service of the United States orders that “no articles of silver plate for the use of the cabin are to be furnished at the expense of the United States.”

3 We don’t know if Com. Preble had a man designated to cook for the cabin. The ship’s muster rolls of the period are silent on the matter.

4 The terms “setter” and “squab” appear to have been regional and common in the south. Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith, who ordered this list, was from Pennsylvania, but the wording might have been inserted by one of his clerks. For more on these terms, see: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2013/documentary-evidence-furniture-forms-terminology-charleston-south-carolina-ii/

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.