Throughout the War of 1812, fortune smiled on USS Constitution. The ship handily bested its foes in battle, but Constitution was also incredibly adroit at evading capture by superior forces. At the very beginning of the war, the crew prevented the ship from falling victim to a large British squadron off New Jersey. April 3, 2014 marks the 200th anniversary of Constitution’s second miraculous escape. This time the ship was fortunate to have the town of Marblehead, Massachusetts under its lee.

After a thorough refit in Boston, Constitution slipped out to sea on the last day of December 1813 and headed for the West Indies. Between the middle of January and the end of March, the ship captured only four vessels, including a 13-gun Royal Navy schooner.

Before leaving Boston, Captain Charles Stewart installed some experimental iron provision tanks, but these had started to leak, spoiling much of the ship’s supply of beef. In addition, the ship’s stem sprung a leak, making about 30 inches of water in 10 hours. While chasing a Spanish schooner near Bermuda on March 19, the ship made a number of heavy pitches into steep seas and cracked the mainmast nearly its whole length. Added to the ship’s problems, some of the crew developed scurvy. In light of these issues, Stewart decided to return to the United States as soon as possible.

Constitution stayed well out to sea to avoid the British blockading squadron in Massachusetts Bay, and finally made landfall off Cape Ann on the evening of April 2, 1814. The crew ran aloft to shorten sail, and the ship hovered off the coast until daylight on April 3. Stewart first intended to sail for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but the wind shifted to the north east, making Boston a better choice. At 8:00 AM, the wind shifted round again to the north northwest and nearly died away. At about the same time, the masthead lookouts spied two square-rigged vessels standing toward Constitution with a fresh breeze from the east — a breeze that had not yet reached the Americans. Soon, the lookouts could tell that the ships were frigates, and the only frigates cruising in company in those waters had to be British.

In fact, they were HMS Tenedos and HMS Junon, two frigates rated to carry 38 guns, but actually armed with 46. Together, they were more than a match for Constitution.

Constitution’s unusual paint job initially perplexed the British crews. Junon‘s Captain Clotworthy Upton afterwards wrote to Vice Admiral Sir Edward Griffith Colpoys in Halifax, saying, “She was painted with a single Yellow Streak, black Stern, and her entire line so perfectly straight, that when her hull first rose above the Horizon, I could scarcely persuade myself she was more than a Corvette.” As they drew closer, however, he could see it was one of the large American frigates: “I know of no other Ship which would answer the description,” he wrote, “except President; that she is an American I have no doubt.”

The breeze no longer favored reaching Portsmouth, and if Constitution couldn’t weather Cape Ann and Thatcher Island, they’d be trapped in Ipswich Bay, with no safe haven under their lee.

At 9:15 AM, with a light breeze, Stewart ordered all sail set and steered to the south. The British ships continued to close quickly, still riding the easterly breeze toward shore. As they got closer, Constitution’s seamen began to lighten the ship. First they “started” the water by breaking down the water casks and pumping it overboard. The broken staves and barrel hoops went in after. Spare yards stowed amidships were next, followed by some beef and pork. With the ship settling too much by the stern, Stewart ordered 1,500 gallons of rum pumped over the side — a true tragedy for the crew!

Jettisoning the stores worked, because by 10:30 AM the officers could tell they were drawing away from the British. The wind that carried the enemy inshore finally reached Constitution, and the ship slowly drew away from its pursuers.

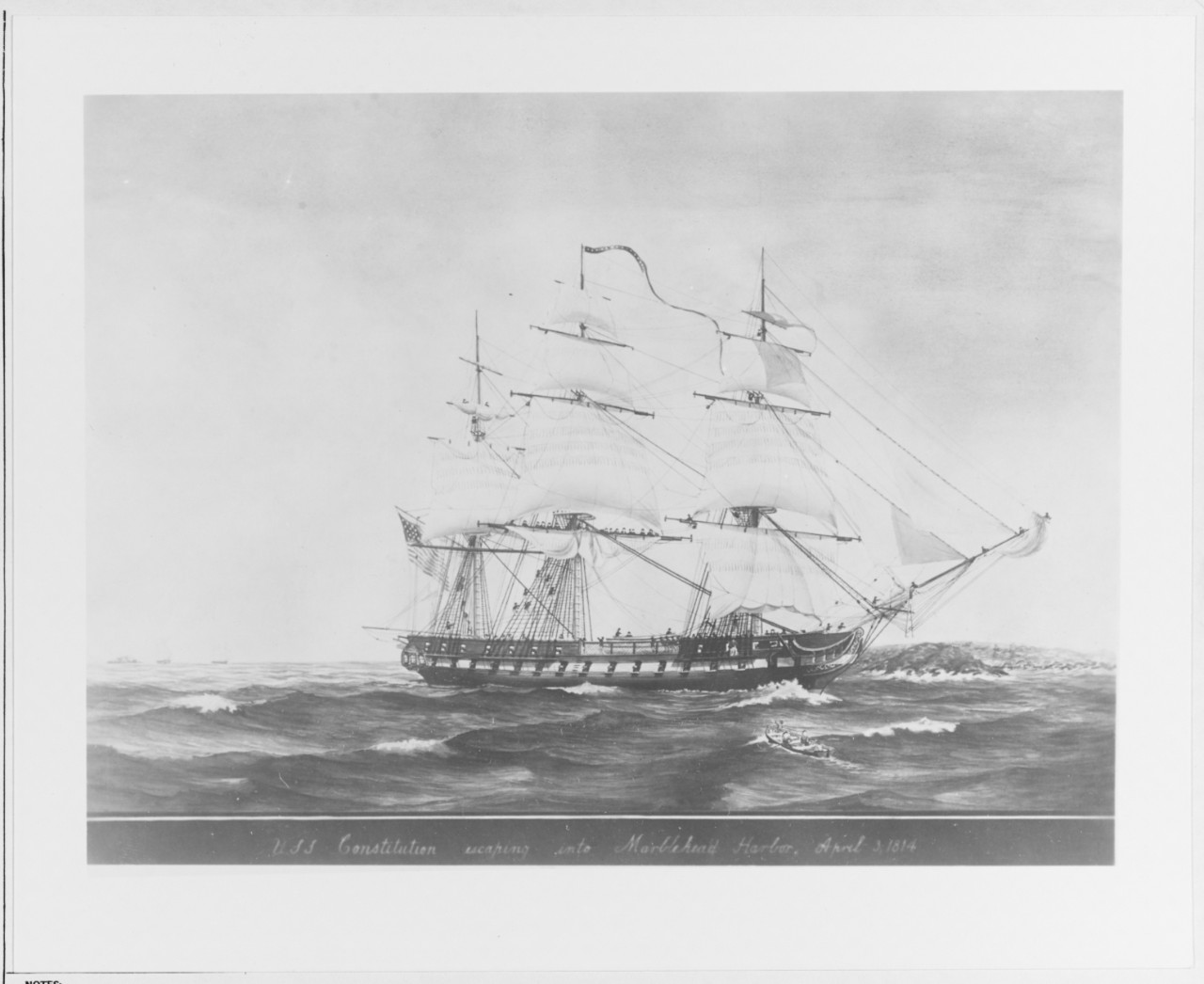

Unfortunately no one on board Constitution knew how to pilot a large ship into Salem Harbor. Sailing a fishing smack among the rocks and ledges was one thing, but bringing in a 1,900-ton warship was something else altogether. Captain Stewart knew he had a large number of Marblehead seamen on board, and the battery at the mouth of Marblehead Harbor would probably deter the British from following him in. He first asked Quartermaster Samuel Anderton to pilot the ship through the rocky channel, but Anderton thought Quartermaster Samuel Harris Green, who had sailed as a ship’s master out of the port, would be a more suitable choice. Green, laid up from a leg injury suffered weeks earlier, hobbled on deck and directed the helmsmen. Stewart and his crew now faced another dilemma. Where there more British ships off the approaches to Boston Harbor? If so, they’d be caught between the Tenedos and Junon and whatever waited for them to the south. So, instead of risking a southerly course, Stewart headed for Salem, where he knew he could anchor in safety near the batteries protecting the town.

At noontime, Constitution rounded Halfway Rock, and stood into Marblehead Harbor. Meanwhile, on shore, the whole countryside followed the chase. At first, there was great consternation in Marblehead, when citizens saw three frigates under full sail bearing down on the town. Many thought there were three British ships coming to attack them. Because the light wind came from astern, Constitution’s spanker — the aftermost gaff-rigged sail — blanketed her ensign. Stewart must have sensed this, because he ordered a sailor to shimmy out to the peak of the gaff to clear the flag. As soon as the people on shore saw the stars and stripes, they sent up a cheer, and the gunners at Fort Sewall, members of the 40th Regiment, U.S. Infantry under the command of Captain John Bailey, shifted their aim from Constitution to the British ships.

Despite the guns of Fort Sewall, Stewart feared Marblehead’s defenses didn’t offer enough protection to his ship. He thought the British might wait until nightfall to attack, and he wanted to put the ship in a more secure anchorage before they struck. Luckily, at 4:00 PM the wind shifted to the south east. Stewart seized the opportunity to sail around to Salem Harbor, where he’d be protected by the guns at Fort Pickering. By now, he had a proper Salem pilot on board, Joseph Perkins, and at 5:30 the ship came to an anchor across from Crowninshield Wharf.At 1:30 Constitution’s anchor splashed down in Marblehead Harbor. The two British ships weren’t willing to risk sailing into unknown waters or face shore batteries, so they gave up the chase and stood about six miles offshore, where they hove too, waiting and watching.

The local newspapers were happy to crow about the successful escape of their favorite frigate. The Salem Gazette recounted the efforts of the local populace, and concluded that in Salem Harbor “she is considered in a state of security… her crew is in fine condition [excluding those with scurvy, presumably], and her safe return is hailed with joy.” The Salem Register echoed these sentiments, saying, “she now triumphantly rides in safety to the great joy of our citizens, who felt so lively an interest in the welfare of this celebrated ship, and her gallant officers and crew.” Report of the ship’s arrival in Marblehead reached Boston the same day, and the Boston Gazette claimed that if news of her getting safe into Salem had not reached town by Monday morning, “a force from 10 to 12,000 men with a considerable train of artillery would have been in Marblehead, to defend their favorite Constitution.”

After a week and half, the coast was clear and the ship made a quick passage down to Boston. It would be another eight months before Constitution went to sea again. This time, she’d fight and capture two ships at once, and then narrowly escape from yet another British squadron.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.