Ah, water. Another one of the luxuries of modern living we take for granted. In most of the western world we turn on the tap and out flows clean, fresh water. We use it for cooking, bathing, and drinking. And we waste a shocking amount of it watering our flower beds and lawns, and washing our cars, sidewalks and a hundred other things that could be cleaned just as well with non-potable water.

Scarcity increases a commodity’s value, and when you’re without water, it becomes very valuable very quickly. Sailors in the early navy learned this as soon as the land slipped below the horizon.

Even though Barnaby Slush could claim, “liquor is the very cement that keeps the mariner’s body and soul together,” water was far more important to his well being at sea. “Seamen,” as one doctor commented, “in consequence of their salt diet, drink a great quantity of water, unless on an allowance.”1 David Porter, in command of USS Essex during a long sea voyage, understood the importance of fresh water when surrounded by an ocean of salt:

As to our water, none could be sweeter or purer; it had not undergone the slightest change. And the only fact I think it necessary to state in support of this assertion is, that a live mullet, nearly three quarters of an inch in length, was this day pumped from a cask filled with the water in the river Delaware: had this water undergone any corruption, the fish could not certainly have existed in it. This little fish I have put in a bottle of its native water, with a view of preserving it alive. From its size, I should suppose it to have been produced from the spawn while in the cask. The water taken in at St. Catharines [on the coast of Brazil], was found to be equally good; and my own experience now enables me to assure all navigators, that the only precaution necessary to have good water at sea is, to provide casks made of well seasoned staves, have them cleansed, and filled with pure water. Should it be necessary at any time (for the trim or safety of the ship, which is sometimes the case) to fill them with salt water, particular care must be taken that they be filled and well soaked, and cleansed with fresh water before they are filled with the water intended for use. These particulars, as I have before observed, have never been neglected by me since I had the command of a vessel; and consequently no one on board has ever suffered from the use of bad water. This is an object that well merits the attention of every commander, when the chief comfort and the health of his crew are so much dependent thereon. For who has experienced, at sea, a greater enjoyment than a draught of pure water? Or who can say that the ship-fever and scurvy do not originate, frequently, in the stinking and disgusting water which seamen are too often driven to the necessity of drinking at sea, even when their stomachs revolt at it?2

If seamen had no qualms about drinking water in which fish had spawned, how truly vile was the average cask of water after being stowed for several months?

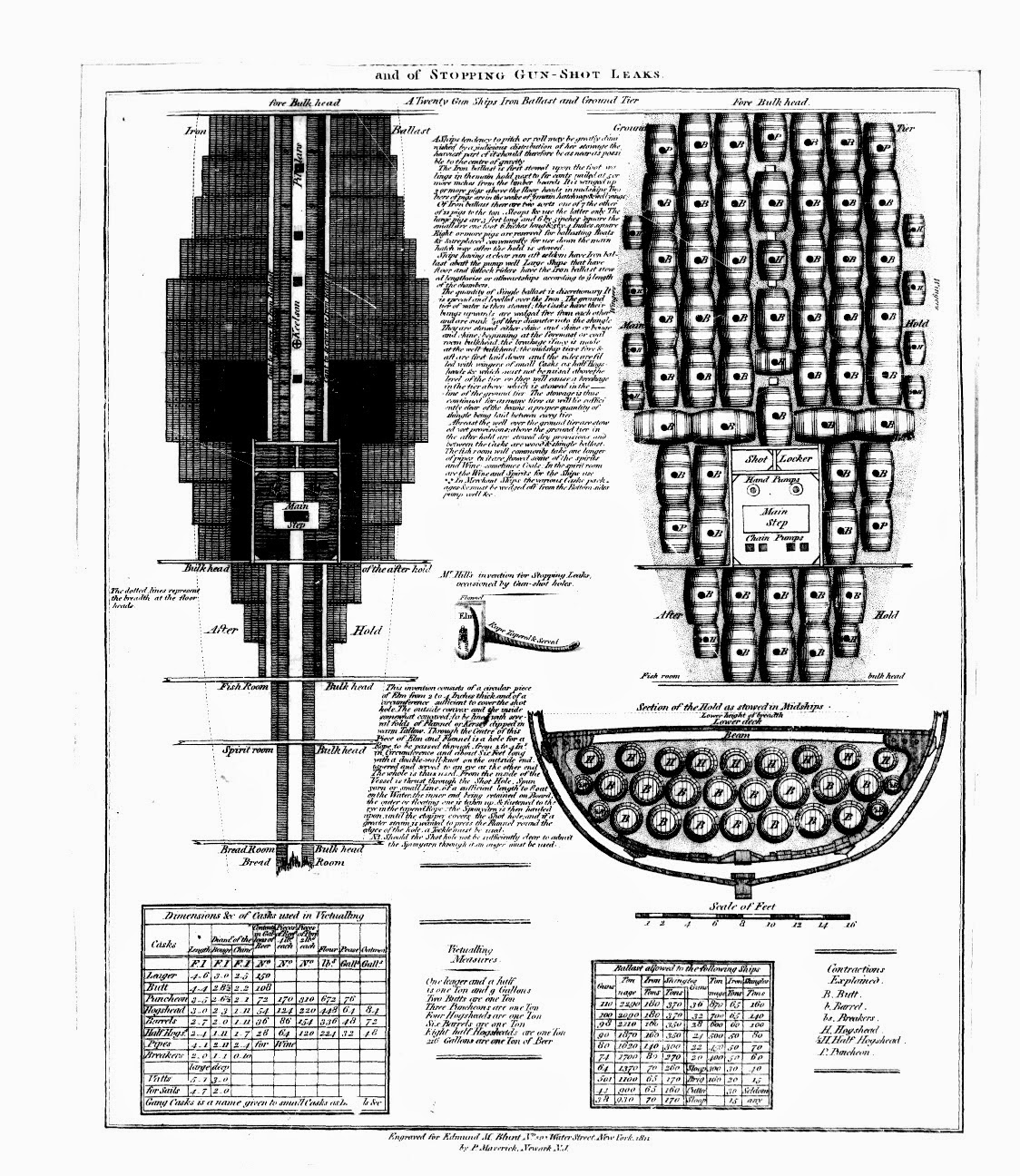

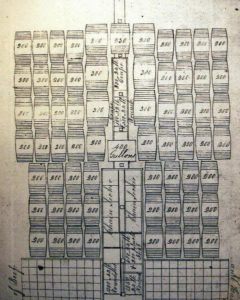

The arid regions of the world to which American vessels ventured often could not provide enough water to replenish the supply. Crews made every attempt to gather passing showers with rain awnings, but they had trouble restocking this vital resource without filling water casks at a proper spring or pool. According to Navy regulations, “one half gallon of water at least shall be allowed every man [per day] in foreign voyages, and such further quantity as shall be thought necessary on the home station, but on particular occasions the captain may shorten this allowance.”3 This edict referred only to the water allowed for drinking, which on a frigate with a crew of 450 meant that the crew consumed at least 225 gallons of water per day. This figure, however, does not include the water expended for cooking, which might require as much as 150 gallons per day. When Constitution sailed from Boston in December1813, she had on board approximately 47,000 gallons.4 According to the testimony of Lt. Henry Ballard, the crew was allotted “250 Gallons, except on pea & rice days when it was 280 till the first of February after which grog water being allowed 310 gallons except on pea & rice days; when it was 340.”5

A water shortage could mean hardship for a crew, especially since it was vital for preparing and cooking salt meat. Marine Fifer Thomas Byron remembered the situation on board Constitution when the water ran low:

Now I will state our sufferings on the night we crossed the equinoctial line, that night all hands came near dying for want of water. A number were dipping up with tin pots the water that had fallen from a small shower into the boats on deck and mixed with the salt water that had flew [sic] over the side into it also old tobacco chews which the men had thrown into the boats and they had to drink it. About daylight it began to rain as it generally does in crossing the line and we were very glad but was not allowed to catch a drop for our messes untill [sic] it was all over, but had to get up casks and spread sails over the deck and fill them and strike them down into the hole [sic]. This was the way we had to live. Every shower the men would run with their pots and cans and stop the scupper holes up to catch the water that fell on deck, dirty as it was they had to use it and sometimes it was so tarry that they could hardly swallow it others running & catching a little here and there upon the painted hamms [sic: hammock cloths] or some other place which would be so painty that it was almost impossible to use it, this was hard for us and I will now account to my readers for it in the first place we dare not venture into a port in the day time so that the enemy could blockade us and having but six months provisions and water on board and daily taking prisoners to help drive it up. We had to put up with two thirds rations of provisions and three pints of water for twenty four hours, this was the cause of the great suffering on board as the men could not eat the salt grub without water and this caused Captain Steward [sic] to search out a by place [sic] to get water, so we run off to Juan Fernandez the place where Robinson Crusoe was cast away…6

However sailors obtained fresh water, it was always a consumed gratefully. We landlubbers don’t know how good we have it.

1 Edward Cutbush, Observations on the Means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors, (Philadelphia, Thomas Dobson: 1808), 119

2 David Porter, Journal of a Cruise Made to the Pacific Ocean, reprint edition (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: The Gregg Press, 1970), 75-76.

3 Naval Regulations Issued by Command of the President of the United States of America, January 25, 1802 (reprint ed., Annapolis, Md., Naval Institute Pres, 1970), 26.

4 Court of Inquiry Record, Captain Charles Stewart, May 1814, RG45, M239, Roll 7, DNA

5 It was common practice for the men to be allowed to drink at will from the scuttlebutt. On Constitution, the scuttlebutt was located on the spar deck, beside the mainmast. See reference to this in the Trial of Quarter Gunner Thomas McCumber, 5 July 1811 (101), M273, Records of General Courts-Martial and Courts of Inquiry, 1799-1867, National Archives.

6 Thomas Byron, “The Narrative of the Cruises of the U.S. Frigate Constitution,” USS Constitution Museum.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.