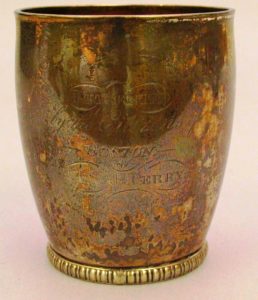

A tiny, tarnished cup hardly seems a fitting trophy for one of the Unites States Navy’s greatest victories, and yet like all artifacts, this piece of silver has a story to tell.

Standing scarcely three inches tall, the silver beaker may lack presence- that is, until one reads the expertly engraved inscriptions. It reads, “Presented by the Citizens of Boston to Com. O. H. Perry.” That’s Oliver Hazard Perry, who led an American squadron to victory over its British counterpart on September 10, 1813. Like Isaac Hull, Stephen Decatur, and William Bainbridge before him, Perry’s victory garnered him laurels- and a whole lot more.

News of the victory reached Boston on Sunday, September 26. The Columbian Centinel described the reaction:

The news of the fresh success of our gallant officers and seamen upon Lake Erie has cheered every American heart, whatever opinion an individual may entertain of the principles which originated the war. On Sunday and elegant salute was fired on board the Constitution after divine [service] in the forenoon, under the direction of Capt. Stewart, in honor of the victory. After the salute the men ascended the shrowds [sic] and gave three cheers, which were cordially returned by thousands of our citizens from the wharves and Copp’s hill. Our brave and experienced tars have averted our fears; and more than realized our hopes, in single combat with the most brave, experienced, and powerful nation on earth; but we still entertain fears for them when they should fight in squadrons or fleets. Com. Perry wears the first garland which the history of our nation will claim in this complicated system of engagement.1

The same edition of the newspaper carried a notice to those citizens of Boston “who are desirous of presenting…a SWORD, or some other appropriate token of respect, to Commodore PERRY,” that a committee would convene at the Exchange Coffee House that very day.2 The committee appointed Mr. John Coffin Jones chairman, and by October 4 the committee had obtained enough pledges to commission an elegant sword and pieces of silver tableware (universally called “plate” in the period) for the commodore. Moreover, if any funds were left over, they were to be transmitted to Perry, who would be instructed to distribute them to “all or any of the indigent widows, orphans or other distressed relatives of the brave Americans who fell in the contest.”3

For the pieces of plate, the committee turned to Boston silversmiths Jesse Churchill and Daniel Treadwell. In their shop at 88 Newbury St., they turned out beautifully executed flagons, bowls, communion cups, and a whole host of other silver wares. As the Boston Daily Advertiser modestly proclaimed, “their zeal and fidelity deserve commendation, and the elegance of the workmanship, it is believed, cannot be surpassed in America.”4

Perry visited Boston on May 1, 1814, where he was wined, dined, and paraded through the streets. No doubt the silversmiths hurried to finish the commission before he left town, but it wasn’t ready until May 17. The committee detached two young gentlemen to Newport, where they presented the hero with the plate “in behalf of the citizens.” Perry gratefully accepted the gift, and made an appropriately theatrical reply: “the flattering encomiums contained in the letter, and the elegant and splendid present, have excited the warmest sentiments of gratitude; and while recollection retains her empire over my mind, the kindness and liberality of the citizens of Boston will ever be properly appreciated by one who has so largely participated in their civilities.”5

The work certainly was fine, but compared to the silver presented to naval heroes by the citizens of Philadelphia and New York, these Boston pieces were positively austere. Was it Yankee thrift that did way with the dolphins and tridents, eagles in full relief, and the heads of Neptune? The centerpiece of the set, a wine cooler or ice pail, survives in the collection of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College. Rings or beckets grasped in eagles’ beaks project somewhat awkwardly from the side, but otherwise the decoration is reduced to a narrow egg and dart motif at the rim and foot.

The beaker or cup in our collection mirrors the cooler’s decorative scheme. This is one of four beakers known to survive. Much of the set was, sadly, stolen from Perry’s descendants decades ago.

1 Columbian Centinel, 29 Sept. 1813.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., 6 Oct. 1813.

4 Boston Daily Advertiser, 27 May 1814.

5 New England Palladium, 27 May 1814.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.