November 10, 2014 marks the 239th anniversary of the United States Marine Corps. Raised for Continental service at the Tun Tavern in Philadelphia in 1775, the Corps performed important services during the American Revolutionary War. Although disbanded in 1783, the Marine Corps was reestablished by an Act of Congress on July 11, 1798. Since then, the Marines have, to quote their well-loved hymn, fought their country’s battles in the air, on land, and sea.

In honor of the Marine Corp birthday, the USS Constituiton Museum hosts an annual Bush Breakfast, a tribute to First Lieutenant William Sharp Bush, who died in combat on Constitution’s quarterdeck during the ship’s battle with HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812.

Born in July 1786 in Wilmington, Delaware, William Sharp Bush came from a family devoted to national service. His father and three uncles fought in the American Revolutionary War. He inherited their legacy of ambition, courage, and love of country. In 1808, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Although he attempted to resigned his commission in 1810, his fellow officer pleaded for him to rethink his decision “in Language, truly flattering to…[his] Character & Feelings.” He joined Constitution‘s crew on June 11, 1812, taking command of the ship’s Marine guard. Just a week later, the United States declared war on Great Britain. On August 19, 1812, Constitution engaged HMS Guerriere about 200 miles east of Halifax, Nova Scotia. At the height of the battle, while Bush prepared to lead his men onto the deck of the enemy frigate, a British musket ball struck him in the cheek. He was the first U.S. Marine Corps officer to die in combat during the War of 1812.

For years, Bush seemed a slightly enigmatic figure. His portrait, probably painted in 1811 by Jacob Eichholtz, reveals nothing. Standing stiffly at attention, hair neatly powdered, uniform immaculate, the young Marine looks every bit the officer and the gentleman. But who was the man in the portrait, the one who inspired so much affection while he lived, and so much regret when he died?

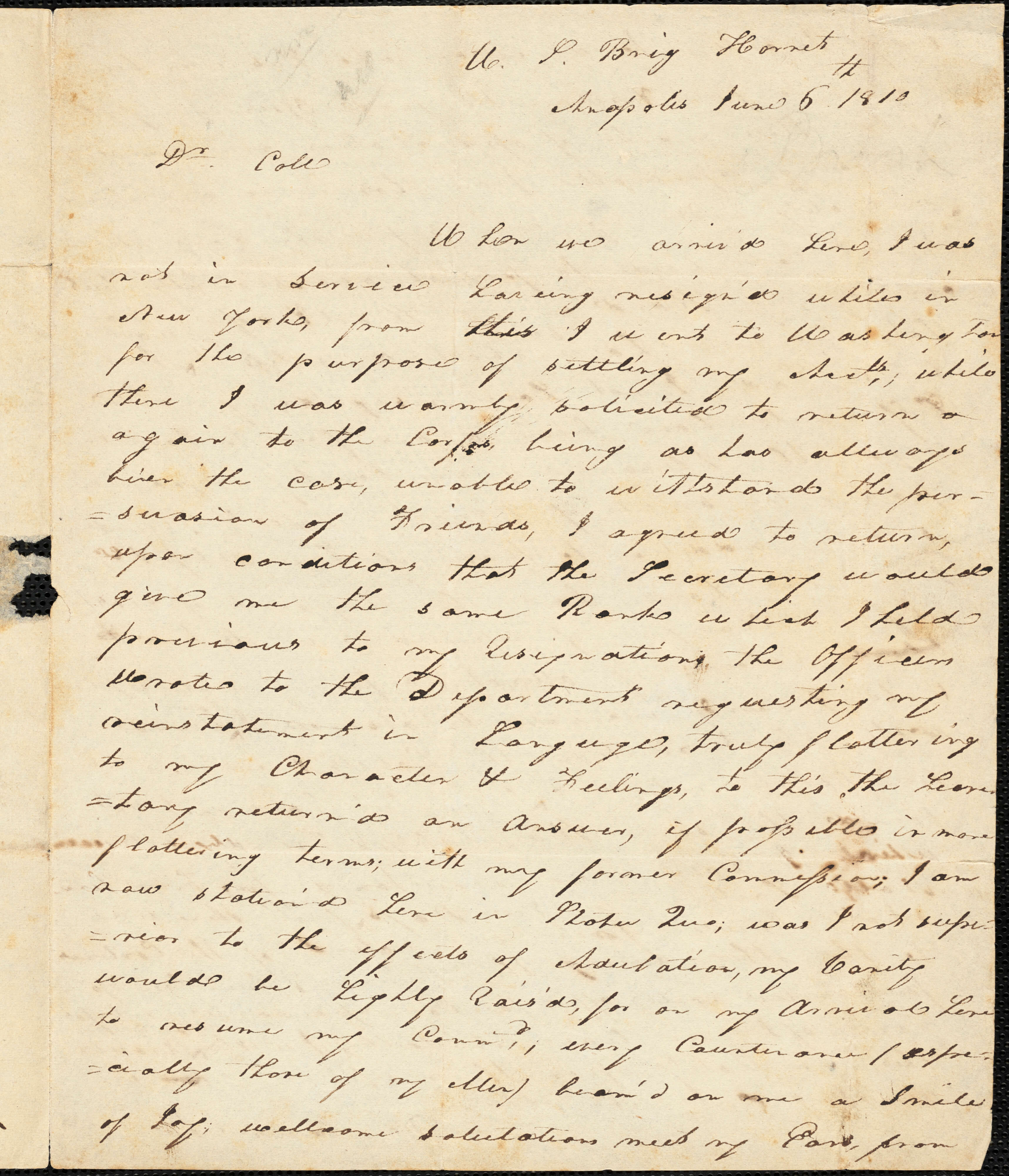

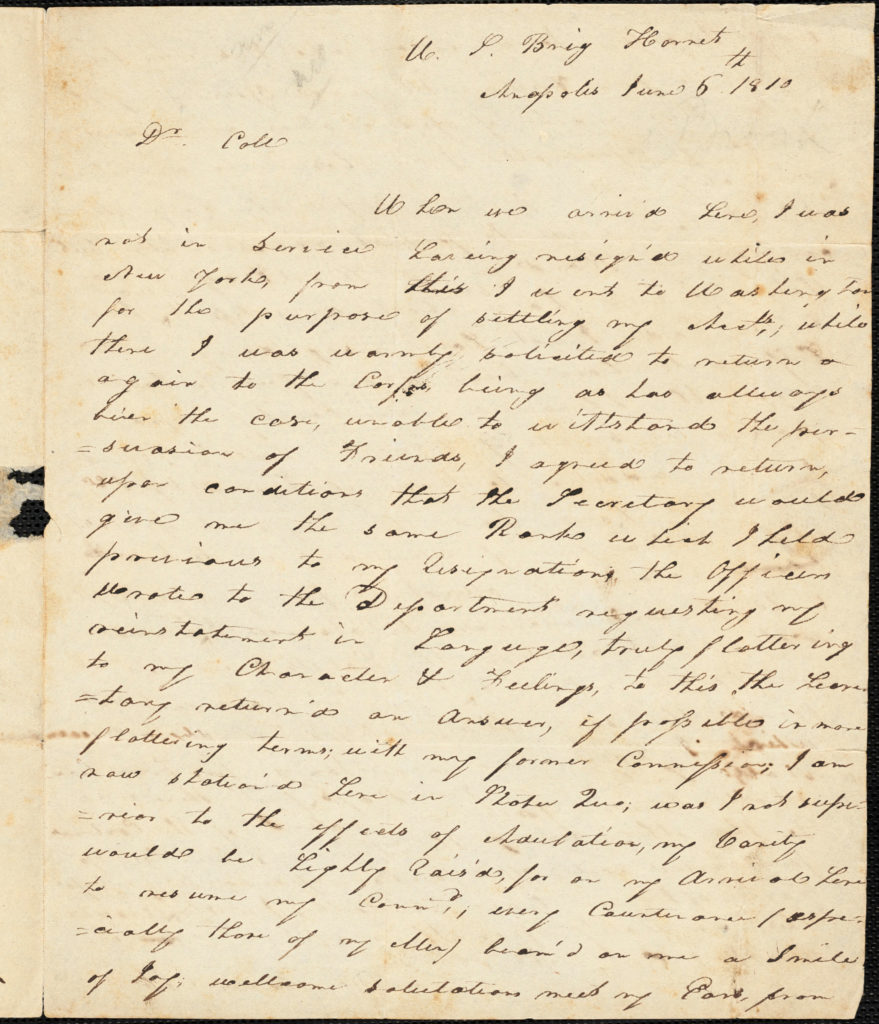

Thanks to the generous donation by Annette and William Doolittle of a pair of letters in Bush’s own hand, we now gain a deeper insight into the officer’s character.

Written in 1810 and 1811 to his friend Captain Jabez Caldwell, the letters overflow with Bush’s personality. He is generous and modest, friendly and humorous. He speaks of his wish to resign his commission, but that he was “warmly solicited to return again to the Corps” and so bowed to the “persuasion of Friends.” When he returned to his command, “every Countenance (especially those of my Men) beam’d on me a Smile of Joy.” Nevertheless, he pines for a return to his Maryland home, because in all the places he has travelled, he has “not yet found the same Hospitality & Friendly intercourse which I have been accustom’d to.”

The second letter encourages Caldwell to visit him at his new quarters in Philadelphia. As an enticement, he describes the delightful situation of the Navy Yard, with its fresh breezes and shady balconies. If Caldwell and his friends come up, “we’ll Drink, Sing & drive dull care away.” And then there are the ladies. Single and 25 years old, he still searches for a suitable wife. Though he has not yet met any of the “Virtuous fair” in the vicinity, he confides that he has his eye on both a “richly Laden Frigate” and an inscrutable “little Island Creek Girl” of their mutual acquaintance.

The letters remind us that even though two centuries separate us, human values and desires have hardly changed. A portrait is both symbolic and representational; it shows the sitter as he was seen and wished to be seen. A letter to a friend is personal, and reveals that duty, friendship, honor, and hope coexist in us all, even in a man who died in combat in August of 1812.

Images and transcriptions of both letters can be found on the USS Constitution Museum’s website.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.