Every year on the fourth Thursday of November, home cooks across the nation fire up their ovens and stoves to prepare a Thanksgiving feast. The ease with which we now boil, roast, braise, fry, sear, and grill our dinners would have seemed nothing short of miraculous to our forebears. With the push of a button or the turn of a dial, we can conjure instantaneous, even heat that remains steady for as long as we need it to. We forget how far kitchen technology has advanced in the course of a few short generations. Even a century ago, though iron cooking ranges had become commonplace, home cooks prepared meals using methods that had changed little in generations. In a way, they had more in common with cavemen than with today’s chefs, surrounded by the latest stainless steel wizardry.

Though it seems incongruous, sailors of the War of 1812 benefited from the latest in cooking technology. To our eyes, the iron stoves with which a navy ship’s cook and his mates prepared daily meals for 450 men seem hopelessly primitive, and yet the sea-going fire hearths of the early 19th century represented an important technological improvement over their predecessors. Until about the middle of the 18th century, most ships’ cooking facilities consisted of ponderous brick structures and copper kettles placed either in the hold or forward on the main deck. As the ship’s structure moved, or “worked” at sea, the bricks inevitably loosened, allowing smoke and even sparks to escape. In addition, the great weight of the bricks put huge strain on a ship’s timbers.

The Industrial Revolution changed all that. By the 1750s, the British Royal Navy began to install iron fire hearths in its ship. The rectangular wrought iron boxes featured kettles for boiling, and open hearths with grates and spits for roasting and grilling. They weighed far less than their brick predecessors and consumed less fuel- an important consideration for a long voyage.1

When the US War Department began to outfit the nation’s new frigates in the 1790s, they naturally ordered the galley stoves from England.2 We don’t have any good description of what Constitution’s first stove looked like, but it may have been similar to the one carried by USS Maryland between 1799 and 1801: “It is made of wrought iron bars each about 3 ½ inches wide, with 2 copper boilers, divided only by a Copper partition.” The boilers, like today’s high end copper pots, were tinned on the inside.3 One on board Constellation in December 1800 came complete with a “smoke jack” and two chains “for spitts.”4 As the hot air rose, a turbine-like device in the stove’s chimney spun, driving a shaft attached by chains to a roasting spit.

In August 1803, as Constitution fitted out for a cruise against the Barbary corsairs, Boston merchant John Bryant provided “one Iron Camboose 27 Inches with Furniture complete delivered on board the Constitution frigate $100.”5 Apart from the height, we know little about the form of this stove. It might have had inferior “coppers” like the one provided to Lt. Richard Somer’s schooner Nautilus:

This day I receiv’d the Camboose on board, & am much pleased with the plan- but do not approve of the Coppers being Cast Iron- They are very ruff – and if not able to stand the fire, or by accident get split, can never be repair’d. I have experienc’d the loss of one on board the United States Commodore Barry, for six Months – It being of Cast Iron would not beare the force of the fire. Commd had them made of wrought Iron- wich las’d untill laid up.6

Officer’s frequently complained of the poor quality and unsuitability of cast iron camboose “coppers”. The two provided to the Portsmouth and the Merrimack in 1798 were condemned after a short time in service. According to Boston Navy Agent Stephen Higginson, “the Boilers and the Hearths were both with what are called fire cracks, which by use have so much opened as to become incapable of use.”7

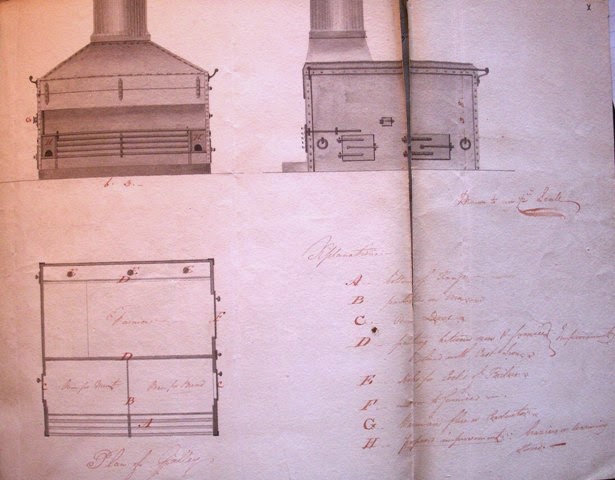

The Constitution camboose of 1803 seems far too small to have provided cooking space for the entire crew, however. A drawing of a stove in store at the Boston Navy Yard in March 1827 gives the measurements as 6 feet 3 inches wide and 3 feet 8 inches tall. In addition, a local manufacturer proposed to make one for a frigate for $2,300- a far cry from the mere $100 spent in 1803!8

By the War of 1812, the Navy seemed to have been able to produce stoves for its own use, though judging from a number of plaintive letters to the Secretary of the Navy from various officers, the supply could not meet the demand. After the war, domestic production increased. In 1820the Washington Navy Yard employed 34 chain cable and camboose smiths led by the eccentric blacksmith Benjamin King.

Of course the camboose was only one part of the galley equipage. In Sept 1813, Boston coppersmith Nathaniel Alley brought down to the harbor from his shop on Union St. the following items for Constitution’s galley: “2 Coppr & 1 Iron Covers for Galley,” “a 16 qrt Coppr Teakettle,” “3 Coppr Saus [sic] Pans with Covers,” “a large Iron ladle & tormentor [a large fork],” and “a large Coppr Cistern for the funnel from the Galley to pass through [an important item that, when filled with water, would prevent the hot funnel from setting the deck on fire].” Apart from a few assorted iron skillets or pans purchased from various merchants, these were the only tools at the cook’s disposal. And yet, considering the level of culinary finesse required to boil beef, pork, peas, and rice, they were wholly adequate to the task.

The purser, or rather the purser’s steward, was also provided with a range of tools to issue out the provisions to the crew. Andrew Green supplied several sets of scales, iron and tin weights, a set of tin gill measures, a “flour shovell,” and a copper hand pump for pumping spirits (or water) from a cask.9

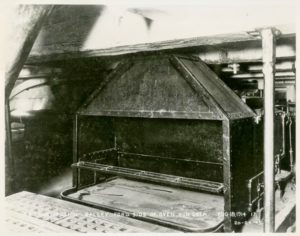

Incidentally, the stove on Constitution today may be the oldest piece of ship’s furniture visible to visitors. It might date to the 1870s, or as late as the 1890s. It appears in photos of the gun deck from 1907, 1914, and 1925. During the 1927-1931 restoration, this stove was turned 180 degrees and fitted with a modern “Shipmate” stove manufactured by the Stamford Foundry Company of Stamford, Connecticut. On this coal-fired range, the ship’s cook prepared meals during the National Cruise.

1 For more on early fire hearths, see Brian Lavery, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 195-199. Contemporaries used the terms fire hearth, camboose, or stove interchangeably to describe these items.

2 Circular to Navy Agents, 5 Jul 1794 M74, Tench Coxe Letters Concerning Military and Naval Procurement, 1794 1796.

3 John Davis of Abel to Thomas Tingey, 8 Feb. 1814, Captain’s Letters to the Secretary of the Navy, RG 45, Vol. 1, NARA. We are indebted to Margherita Desy for sharing this letter.

4 Alexander Murray accounts, 4th Auditor Settled Accounts, Alphabetical Series, RG 127, Box 1914, NARA.

5 Navy Agent Samuel Brown Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

6 To Secretary of the Navy from Lieutenant Richard Somers, U S Navy,Baltimore, June 2nd 1803, in Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers vol. II (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1940), 433.

7 Extract of a letter from Stephen Higginson, 3 Jan. 1799, in Miscellaneous Letters Sent by the Secretary of the Navy, M209, Roll 1, 474, NARA.

8 W. Whall and Son to Board of Navy Commissioners, 5 Mar. 1827, RG 45 E-327 Reports, Returns, and Estimates Received from Navy Agents, Sept 1814- Apr. 1834, NARA.

9 Voucher to Andrew Green, Dec. 11, 1813, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, box 38, NARA.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.