On February 17, 1815, President James Madison signed the Treaty of Ghent, officially putting an end to the War of 1812. But for Constitution, at sea 3,000 miles away, the war was not over yet. February 17 is the 200th anniversary of Constitution‘s last victory of the war. In fact, apart from a few shots fired in anger in later years, this was the last time the frigate engaged in active combat during its long career.

Having escaped from British blockaders off Boston on December 18, 1814, the ship and its veteran crew had spent the last two months cruising Atlantic sea lanes in search of prizes. While they’d made a few captures, they still had yet to fall in with a real prize — a British convoy bound to or from the West Indies and the Mediterranean.

Steering southwest from Portugal, by February 20 they were about 60 leagues (180 nautical miles) east northeast of the island of Madeira. The light northeast breeze failed to dissipate the slight haze hanging over the water, but at 1 PM the masthead lookout distinguished a large ship sailing to the southwest. A half an hour later he spotted another further to the westward. Anxious to discover their true character and to prevent their joining company, Constitution’s crew raced aloft to set every sail, and the chase was on.

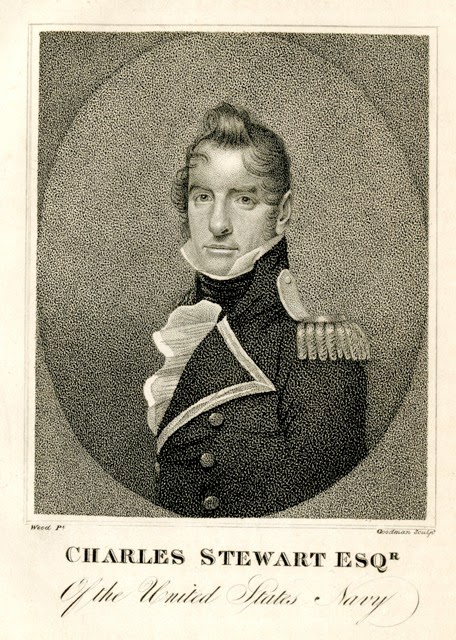

[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 1293.1.]

Captain Stewart sat astride the hammock nettings directing the action, seemingly immune to British shot.2 Constitution’s forward guns played upon the Levant, while the after most guns took aim at Cyane. In an attempt to close the range (to maximize the hitting power of his carronades), Cyane‘s Captain Falcon spilled the wind from his maintopsail, and allowed Constitution to forge ahead. He put the helm down and tried to edge up onto the American’s lee quarter. Perceiving the danger, Stewart fired a broadside into Levant, ordered Constitution’s mizzen topsail backed, and “closed with the sternmost ship under the cover of the smoke” — a demonstration of supremely fine ship handing!3 By 5 PM, the ships had closed, and Stewart ordered two guns fired to try the range. The shot fell short. The British vessels attempted to work to windward of the Americans, and thereby claim the coveted “weather gauge.” Constitution’s superior sailing foiled them, however, and they started the action to leeward of their opponent. At about 6 PM, the British shorted sail and formed a line astern with Levant leading, about half a cable’s length (360 feet) apart. At 6 PM, all the ships hoisted their ensigns (the British ships both wore red ensigns) and five minutes later Stewart ordered a single shot fired between the two ships as an invitation to commence the battle. Almost instantly, the broadsides of the three ships erupted in a torrent of smoke and fire.1

Constitution received little damaged in the engagement, and by 1 AM, the ship was ready to fight another battle. Cyane and Levant, however, suffered considerably. According to American Midshipman Pardon Mawney Whipple, “the decks of both vessels were literally covered with dead & wounded.” As part of the prize crew, he spent the next three days on board the Levant:

“[T]his being the first action I was ever in, you can imagine to yourself what were my feelings to hear the horrid groans of the wounded & dying, & the scene that presented itself the next morning at daylight … the quarter deck seemed to have the appearance of a slaughter house, the wheel having been carried away by a shot – killed & wounded all around it, the mizenmast for several feet was covered with brains & blood; pieces of bones, fingers, & large pieces of flesh were picked up from off the deck [.] T’was a long time before I could familiarize myself to these & if possible more horrible scenes that I witnessed.”6

Despite the two-to-one advantage of the British, it had hardly been a fair fight. Constitution’s heavier guns and heavy timbers were able to both deal out and absorb more punishment than its opponents. Still, it was a fine accomplishment, and both the U.S. Navy and the American press were quick to sing the praises of ship and crew. Constitution’s adventures were not over yet, however!

1 Charles Stewart to the Secretary of the Navy, May 15, 1815, Captain’s Letters to the Secretary of the Navy, RG 45, Microfilm 125, Reel 44, National Archives and Records Administration.

2 Henry B. Joslin, “Naval Asylum Biographies,” Navy Library, Washington, D.C.

3 USS Constitution Log, February 21, 1815, 24, Microfilm 1030, National Archives and Records Administration.

4 Joslin, “Naval Asylum.”

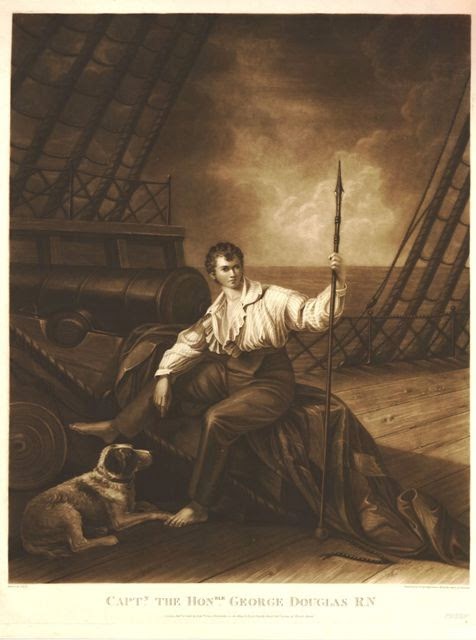

5 George Douglas to First Secretary of the Admiralty, February 22, 1815, ADM 1/170, National Archives, United Kingdom.

6 Pardon Mawney Whipple’s Letterbook, 1813-1821, USS Constitution Museum Collection.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.