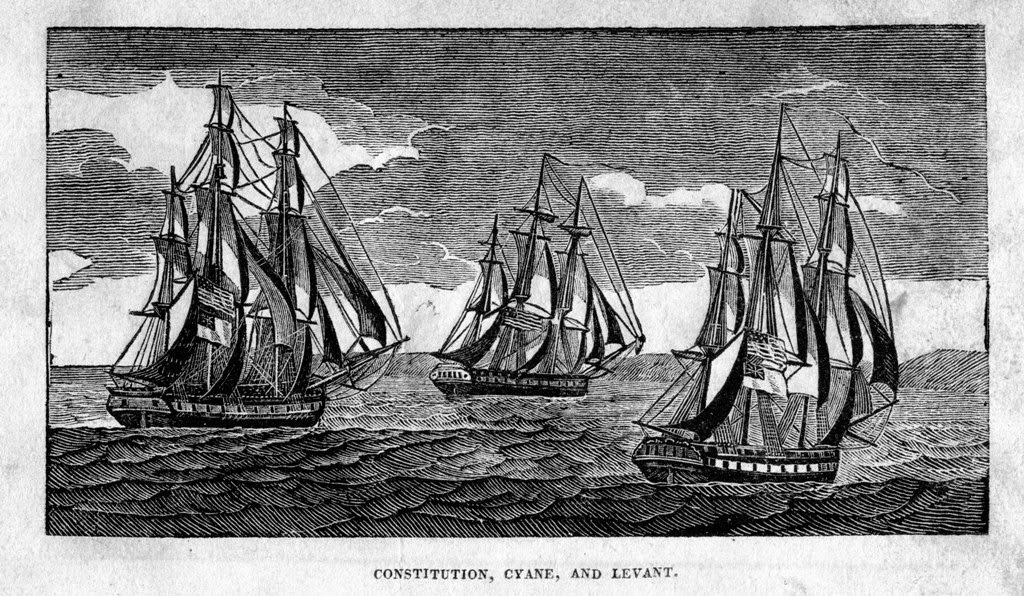

On February 20, 1815 the Constitution handily captured two British prizes. With shot holes stopped and rigging mended, Captain Charles Stewart had a choice. He could risk returning directly to the United States, where the likelihood of encountering a British blockading squadron was high, or he could sail to some neutral island, land the prisoners, and wait for news of the peace treaty he knew was coming. Though everyone on board anxiously wished to return home, Stewart chose the prudent option. The ship and her prizes steered for the island of Santiago, in the Cape Verde archipelago, and anchored at Porto Praya (modern Praia) on March 11. The islands were a possession of Portugal, and therefore a neutral port.

Constitution and Levant sailed well, but the Cyane began to fall behind. At 1:10 PM, Stewart signaled to Cyane (now under the command of Lt. Beekman Hoffman) to tack to the northwest, hoping to draw some of the pursuers away. But the British paid no attention, and kept following in the wake of Constitution and her smaller consort. By 3 pm, Constitution’s superior speed had given her a considerable lead, but the poor Levant began to find herself in danger. Midshipman Pardon Mawney Whipple narrates what happened next:

[T]he Capt apprehensive that should she be brought to action in company with the Constitution, it might endanger the latter ship, therefore found himself under the necessity of sacrificing the Levant to save her, the signal was made for her to tack, which was promptly obeyed & astonishing as it may appear to every brave man, the enemy squadron tacked in succession after the Levant & abandoned the Constitution, when it was reasonably supposed by all onboard, even the English officers [the prisoners], that had the most tryfling accident happened, she must have inevitably fallen into their hands – they (the Englishmen) raved like mad men when this circumstance took place.

The British squadron commander, Sir George Collier, could never adequately explain why he let Constitution escape. The decision haunted him, and he eventually committed suicide in 1817.

As Constitution sailed merrily over the horizon, the British turned their attentions to the Levant. The prize captain, Lt. Henry Ballard, knew he couldn’t outrun them in a long chase, and so decided to return to Porto Praya in hopes that the Portuguese governor would respect the Americans’ right to anchor in a neutral port. Unfortunately, the Portuguese authorities were unwilling or unable to prevent the British from attacking the American prize. In fact, the British prisoners who had been previously landed by Constitution’s crew left their place of confinement, went on shore to the fort guarding the harbor, drove the Portuguese soldiers from it, and opened fire on the Levant with the entire battery.

According to Marine Private Henry B. Joslin, part of the prize crew on Levant,

We ran into the Cove to avoid the shot and beached our ship, but it being very bold water, she did not stick, we let go an anchor under foot, and only veered enough [cable] to hold her, so we could not be in sight of the fort. Then the frigates came in one after another and gave us a broadside & stood out. [A] boat from Leander came alongside (as we had struck before the vessels had entered or fired into us, knowing we were entirely at their mercy) and enquired “what ship is that.” Lt Ballard answered “it is late H.B.M. ship Levant,” and also said, “you are a set of dam rascals for firing into a ship with her flag struck.”

Constitution was still filled with British prisoners, and with provisions and water running low, Capt. Stewart knew he had to offload them before returning to the United States. Standing across the Atlantic, the ship reached St. Louis de Maranham (São Luís, on Maranhão Island) on the coast of Brazil. After successfully landing all of the prisoners – a process that took nine days- the ship sailed for home. They touched briefly at San Juan, Porto Rico in April 28, and here learned the news that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed and ratified. Midshipman Whipple called it “the most unwelcome news that I ever received,” for gone were his chances of glory and promotion.

The ship and her weary crew at last made it to New York on May 15th. They found the Cyane waiting for them. Three days later, the men captured on the Levant arrived. According to Private Joslin, “as we passed her, we of the old crew gave three cheers for the old Constitution. Then Comr. Stewart hailed, asking what men were those & I want them all.”

And so Constitution’s War of 1812 adventures ended. The crew paid off or transferred to other ships, and the old frigate laid up in ordinary, it would be six years before she raised her anchor for another voyage.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.