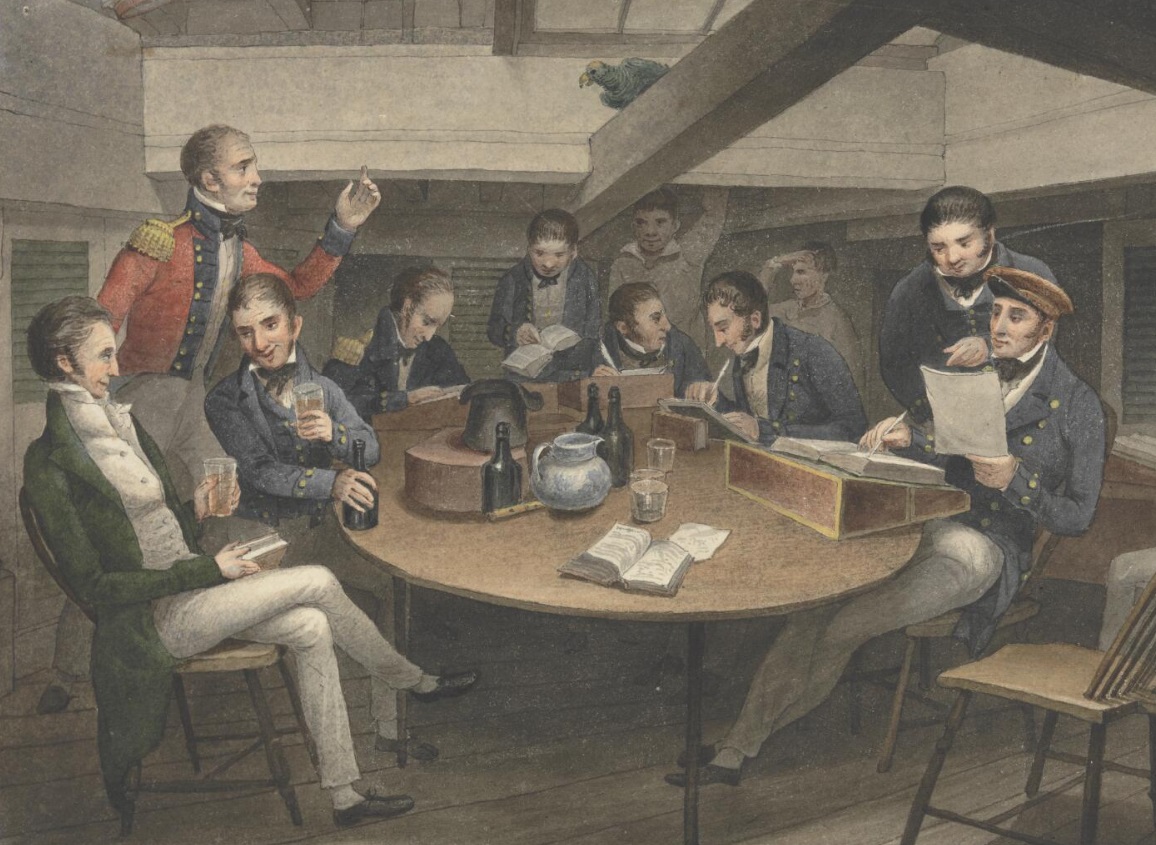

When one imagines the rough and ready interior of a sailing man-of-war prepared to sail on a cruise against an enemy fleet, it is a scene replete with iron cannons, rope and tar, bronze-faced sailors, and other implements of war. All of these things were rugged or deadly, and rightly so. Amid such scenes as this, probably the last thing to come to mind is glassware for the dinner table! And yet, as many surviving US Navy purchase receipts attest, the luxuries of the table rose high on the list of officers’ necessities.

In their view, a man had to live like a gentleman to act like one and be treated like one, so domestic trappings mattered. Just as American captains outfitted their cabins with upholstered sofas, mahogany tables, and fringed silk curtains, their dining tables were covered with appropriately fashionable glasses.

In October 1812, as Constitution was repaired and outfitted for her next cruise, Boston glassware dealer Daniel Hastings made a delivery to the ship. Nestled safely in crates filled with straw were three dozen half-pint cut glass tumblers and an equal number of wine glasses. In May 1813, just before her fatal encounter with HMS Shannon, the frigate Chesapeake received “2 Doz[en] Finger’d Tumblers” (they cost $12) and the same number of wine glasses, as well as a pair of ringed quart decanters.1

“The Constellation’s cabin contained four apartments;— the forward cabin, which was the dining room, the after cabin, a circular apartment which served for a parlour, and two state-rooms. The only furniture of the forward cabin was a large mahogany side-board, whose top was perforated with holes for tumblers and wine-glasses, a set of plain curly-maple chairs, and two cherry tables.” 2

1 Voucher to Daniel Hastings, Oct. 20, 1812 and May 22, 1813, Amos Binney Settled Accounts, 4th Auditor of the Treasury Alphabetical Series, RG 217, Box 39, NARA.

2 Enoch Cobb Wines, Two Years and a Half in the Navy; or, Journal of a Cruise in the Mediterranean and Levant, on Board the Frigate Constellation in the Years 1829, 1830, and 1831 (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1832), 23.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.