In 2015, the Wall Street Journal published an alarming report that American whiskey distillers were facing an imminent shortage of the white oak barrels critical for giving bourbon its distinctive taste.1 According to the article, the explosion of craft distilleries corresponded with a reduction in the American white oak harvest, as well as the closure of some stave mills, the manufactories that transform the raw timber into the narrow strips of wood that make up the sides of a barrel. Barrel production could simply not keep up with demand. Thankfully, industry insiders agree that while some of the smallest distilleries may have trouble getting their hands on new white oak barrels, the larger distilleries enjoy long-term contracts with cooperages and have not felt the pinch.

A barrel shortage would have seemed unthinkable a few generations ago. Until WWII, wooden barrels were the container of choice for a wide range of goods. When Constitution slid down the ways into Boston Harbor in 1797, barrels, along with crates and bales, were ubiquitous anywhere bulk goods were bought, sold, transported, or stored.

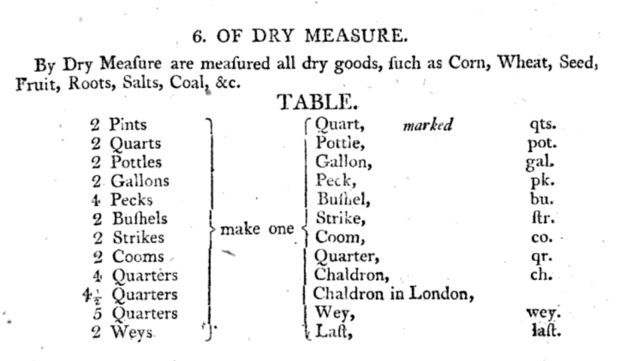

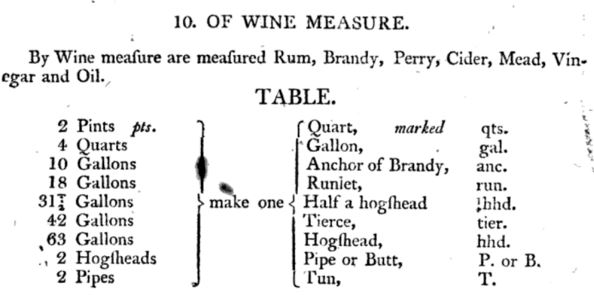

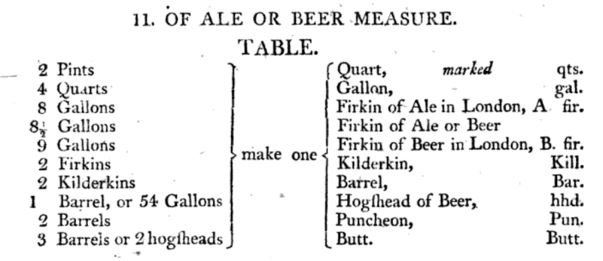

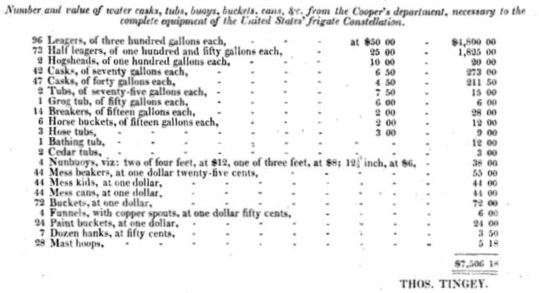

Even the meaning of the word “barrel” has been forgotten. Today, we use it to denote any wooden container with two flat heads and curved sides, but historically the word “cask” was a generic container. A “barrel” was a specific volume measurement. In fact, there was a whole range of specific containers made to hold different volumes of wet and dry goods, as the following tables demonstrate.

Making casks, a trade called “coppering,” was an important job in any seafaring town. Naval vessels usually carried a cooper as well, because without tight, well-made casks, the operational range of a vessel could be severely limited. If the brine oozed from the salt meat or the fresh water leaked into the bilge, a ship had no choice but to seek the nearest friendly port to reprovision. Naval coopers were rated as petty officers, received $18 per month for their troubles, and reported to the ship’s carpenter.

The following list of casks purchased for the frigate Constellation shows just how large a job this could be:

It should be noted that the coopers on board naval vessels rarely made a cask from scratch. The Navy purchased most of its casks ready made from civilian coopers. The ship’s coopers were tasked with keeping them in good repair, and also “shaking” or breaking down empty casks. As the crew consumed the ship’s provisions, the cooper carefully disassembled the the barrels, butts, hogsheads, and firkins, and bundled the pieces so they could be reassembled when needed.

We know the names of two coopers who served on Constitution during the War of 1812. John Northrop joined as a seaman in 1811, but was promoted to cooper in 1812. He saw action in the battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, and left the ship after her return to Boston in 1813. Boston-born cooper Alexander Lane joined Constitution’s crew in April 1813 and served through the rest of the war. After his discharge in June 1815, he worked at his trade in several different shops around Boston, most of them on one of the town’s busy wharves, and finally enlarged his business to include furniture making. He retired to East Boston and died in 1852 at the age of about 66.

1 The Wall Street Journal, 11 May 2015.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.