There is no doubt that a sailor on board a ship like Constitution lived a hard life. His daily duties put his life and limbs in jeopardy. Constantly exposed to variable weather, to heat and cold, his good health was often sacrificed for the good of the ship and his shipmates.

Luckily, the U.S. Navy made provision in its laws and customs to take care of sick and hurt sailors. The accommodations for the sick on board a sailing warship might seem crude, if not downright cruel, to us today, but access to free medical care administered by a trained doctor was a perk few laboring men on shore could have enjoyed.

Mild indisposition was not enough to excuse a sailor from duty, but severe sickness, disease, and injuries often earned him a stay in the ship’s infirmary. Called the “sick bay,” or “sick berth,” the ship’s hospital was a place where the sick could be nursed back to health, isolated from the rest of the crew. Herman Melville, in his novel White Jacket, describes the sick bay on board the fictional frigate Neversink:

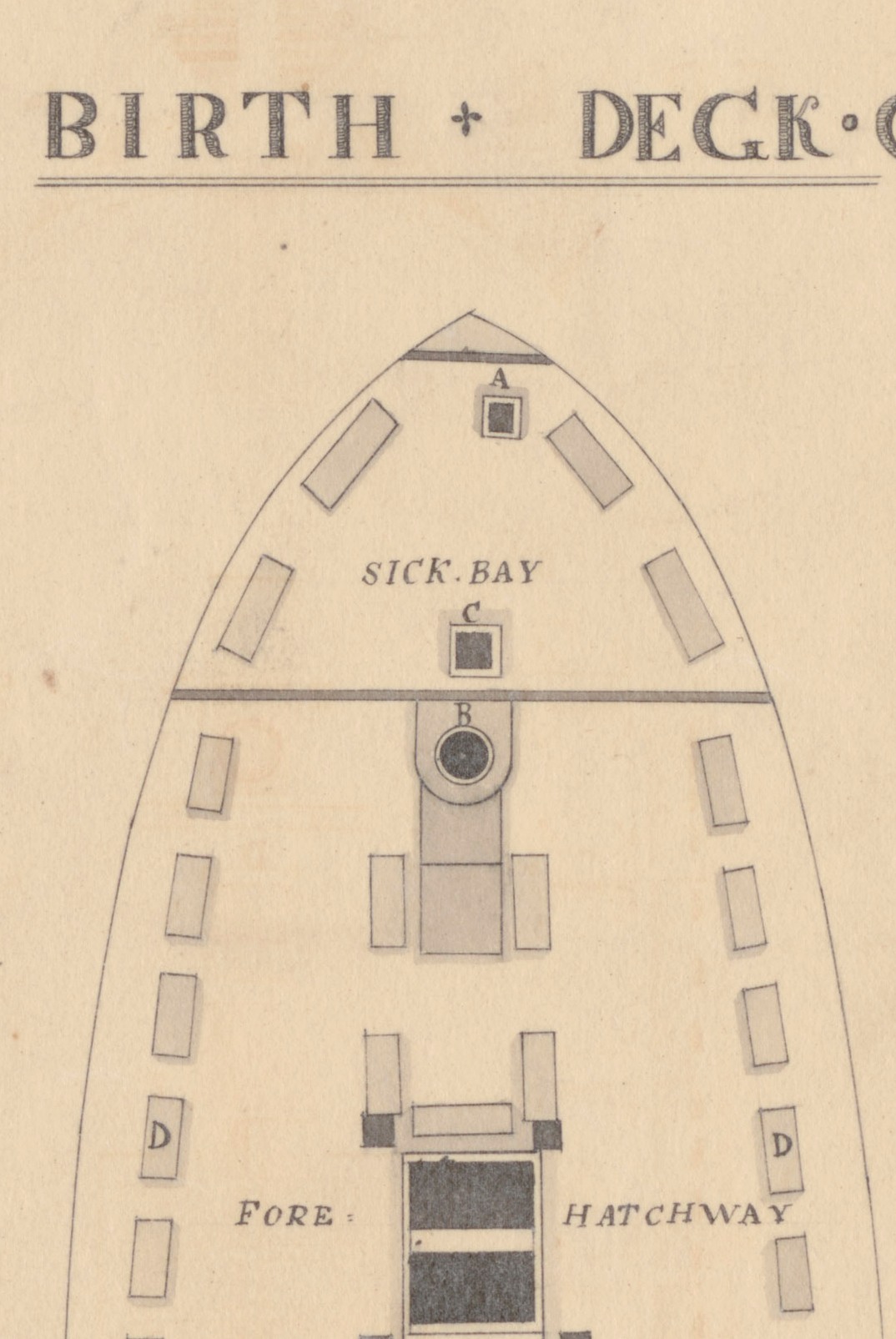

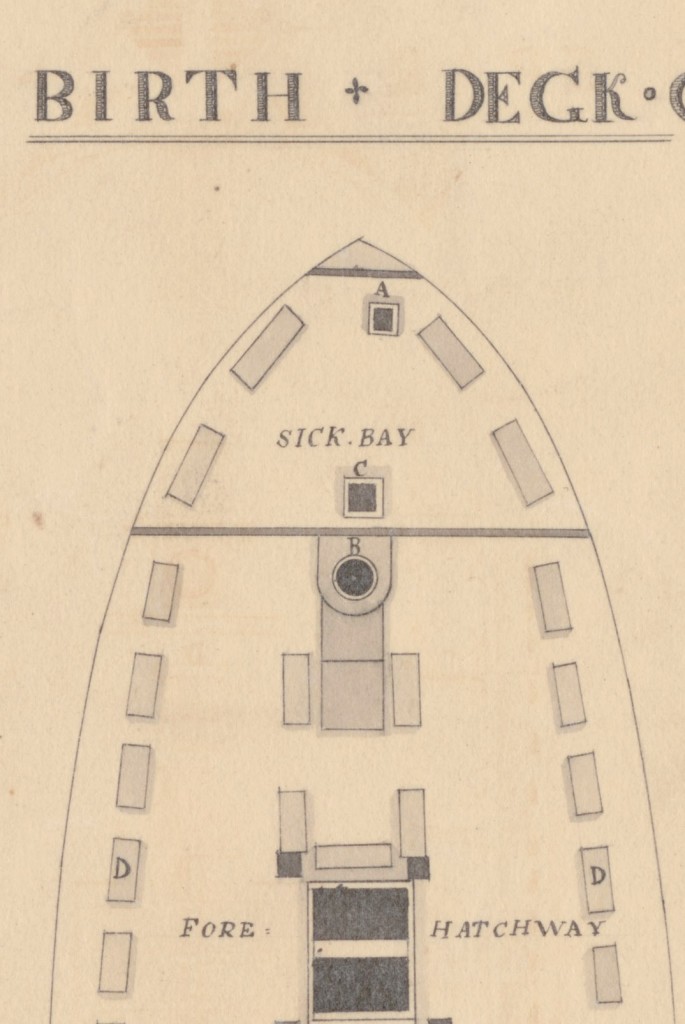

“The sick-bay is that part of a man-of-war where the invalid seamen are placed; in many respects it answers to a public hospital ashore. As with most frigates, the sick-bay of the Neversink was on the berth-deck—the third deck from above. It was in the extreme forward part of that deck, embracing the triangular area in the bows of the ship. It was, therefore, a subterranean vault, into which scarce a ray of heaven’s glad light ever penetrated, even at noon.”1

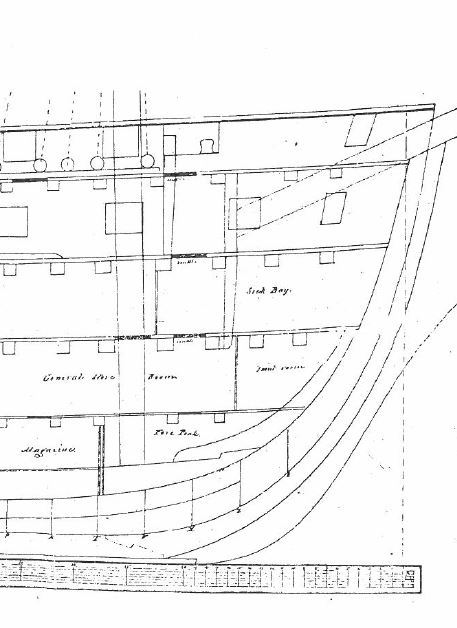

Melville drew on his experiences sailing on board the USS United States in the 1840s. This is an important detail, because by that date, the location of the sick bay had been firmly established. Crammed into the bow of the ship on the berth deck, the sick bay was removed from the hustle and bustle of the gun deck and the periodic tumult that came to the berth deck when the watches changed. And yet, as we dig deeper into the details of life on board American warships at the beginning of the 19th century, it seems the location of the sick bay, and its usefulness as a place of recuperation for the sick, was in flux.

The first indication that the sick bay was perhaps not always placed in the bow comes from naval doctor William P.C. Barton in 1814. Barton was deeply concerned about the quality of the air that patients were exposed to. He wrote:

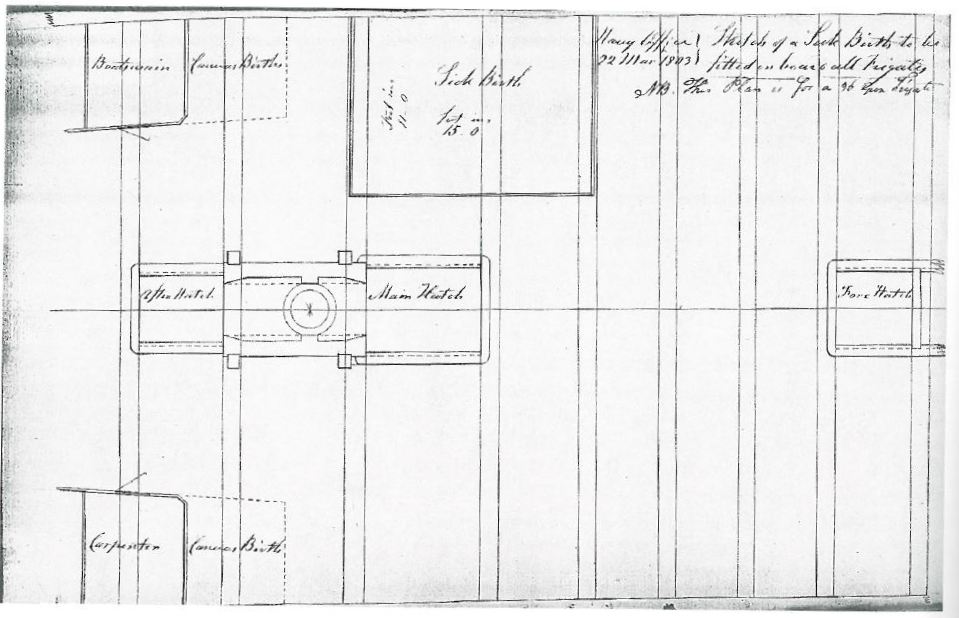

“The sick-bay in double-decked vessels, is usually placed amidships, and is separated from the other part of the berth-deck only by means of a tarpaulin, or canvass curtain, and sometimes not even by these.

From the situation of the bay, then, it is necessarily exposed to the damp air of the cable-tier, as well as the cold air of the mid-hatch above it, which is generally open, at its after end; and to the unpleasant smell of the fore-hold, where the beef, pork, &c. are kept; as well as the cold air that blows down the fore hatch, at its forward end. The screens or curtains of which I have spoken, are but ineffective barriers to these unhealthful currents. Added to this, the berth-deck, according to the existing usage of the navy, is frequently, if not daily, wetted. Can any place, then, be conceived of, better calculated to injure the patients and distress the surgeon, then such a sick-bay?”2

Barton was not merely a complainer, but was also a reformer. He offered this suggestion:

“I see no reason why the sick-bay should not be constructed farther aft, or chock forward: that is to say, between the steerage and root of the main-mast, or forward of the fore-mast. It should, too, be encompassed or partitioned off by moveable bulk-heads, lined with baize, and should be ventilated by tubes from the gun or main-decks. It should be furnished with small and well-slung cots, in such number as it will conveniently contain. In the summer season, perhaps, it would be more conducive to health and comfort, to have the sick-bay amid-ships, where it now usually is placed; but I have seen too much of the inconvenience and danger of placing sick men in this place in the winter season, not to think it highly necessary that some change should be made.”3

The concern for fresh air was foremost in the minds of naval doctors, because according to the medical theory of the day, bad air caused and contributed to a wide range of illnesses. A note in Constitution’s logbook on December 29, 1814 makes this connection explicitly: “Got the sick off the birth deck and birthed them under the half deck for the benefit of the air.”4

“I will now descend a story lower: we come to the Birth deck so called, because originally used for swinging the men’s hammocks during the night, though the main deck is now also employed for that purpose. . . . The birth deck however, properly so called extends only a little abaft the mainmast: in its centre is the sick bay, a room with bulkheads of open work and forming our hospital, now well filled, for a large number of our men sick. This deck is supplied with air by a range of air ports twelve inches by eight, a few feet above the water mark; they are closed at sea.”6

Despite these scattered references, we can’t be sure of the location of Constitution’s sick bay in her early days. The earliest plan to show the ship’s sick bay is dated December 1847, and by that point it encompassed the area forward of the fore mast on the berth deck. Hopefully further research will help us discover the reality of yet one more detail of daily life on Constitution.

1 Herman Melville, White Jacket, or The World in a Man-of-War (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1970), 325-326.

2 William P. C. Barton. A Treatise Containing a Plan for the Internal Organization and Government of Marine Hospitals in the United States: Together with a Scheme for Amending and Systematizing the Medical Department of the Navy (Philadelphia: Edward Parker & Philip H. Nicklin, 1814), 237-38.

3 Ibid.

4 The “half deck” is the portion of the gun deck just before the captain’s cabin.

5 Robert Gardiner, Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 101-102. In British ships-of-the-line, sick bays were typically located forward on the main gun deck, under the forecastle. See Dr. John Gray to William P.C. Barton, April 19, 1811, in Barton’s Treatise, 151.

6 George Jones, Sketches of Naval Life, with Notices of Men, Manners and Scenery, on the Shores of the Mediterranean, in a Series of Letters from the Brandywine and Constitution Frigates, 2 vols. (New Haven: Hezekiah Howe, 1829), 4-5.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.