The deeper one digs into the origins of the frigate Constitution, the more one is struck by a glaring absence in the record of her early days. The documentary record of her design and birth is fairly complete, for many of the letters between the War Department, her designer, and her builder still exist. But what we lack are visual representations of the ship when she was new. The now famous portrait of the ship executed by Michele Felice Corne about 1803 is the earliest known depiction of Constitution, and yet this reflects her appearance after substantial alterations.

It is remarkable, and not a little maddening, that no sketches, drawings, engravings, or paintings of the ship in her earliest form have survived. In a town filled with amateur and professional artists, someone must have delineated the graceful form of what the Boston press called, “one of the finest vessels that ever floated.” It may be that such a work still exists out there in the world, mislabeled, or unrecognized for what it is, waiting to be rediscovered.

In the meantime, our searches have uncovered two interesting and early images of the frigate United States. Built by Joshua Humphreys in his Philadelphia shipyard, the United States was, like Constitution, designed as a 44-gun frigate. During her construction her form was somewhat altered by the addition of a “round house” or poop cabin that gave her stern a lofty profile and, as it turned out, severely hampered her sailing ability. This additional structure was probably removed or significantly altered during the ship’s 1805-1806 refit.

Historians and modelers (those students of the particular), have long argued about and guessed at what this structure looked like, and how it was integrated into the ship’s overall form. Two engravings, published about three years apart, and seemingly hiding in plain sight, might finally provide some answers.

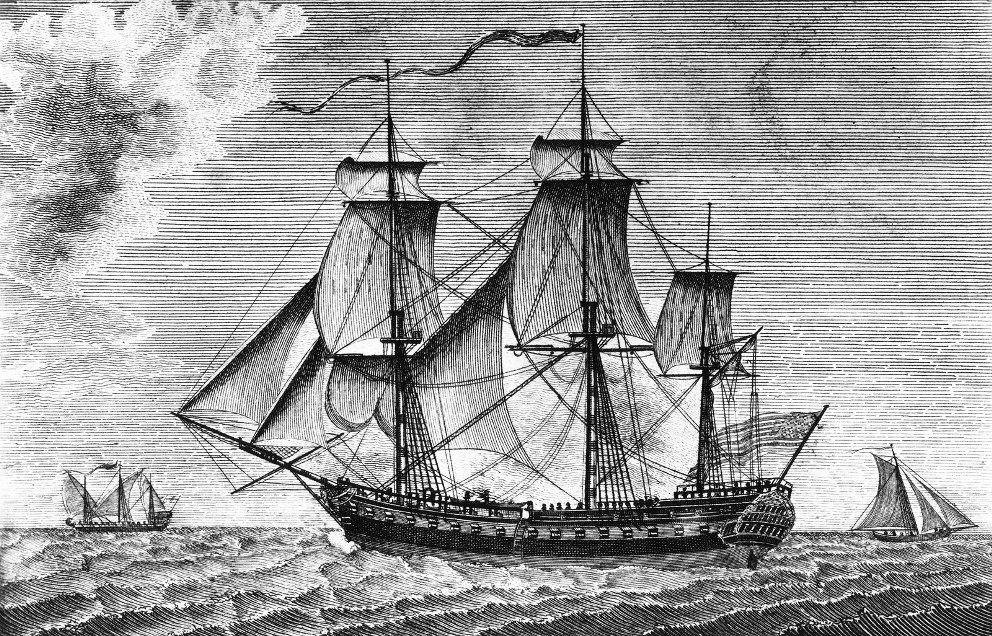

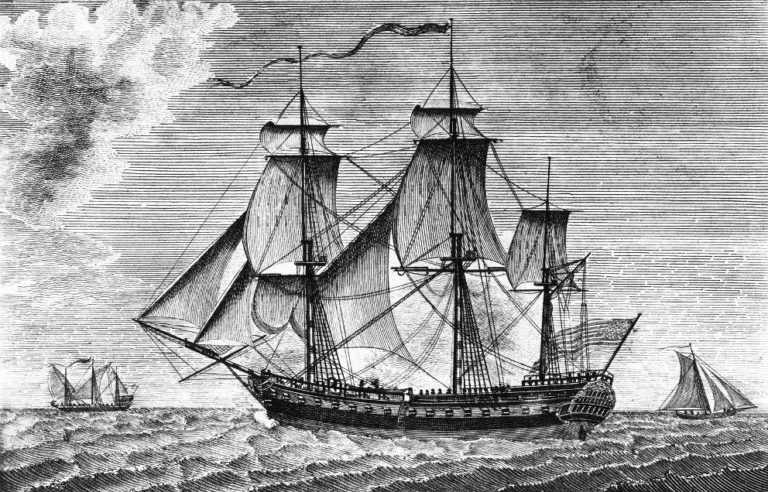

In July 1797, the short-lived American Universal Magazine published a new engraving by Thomas Clarke titled “Frigate United States.” This was two months after the ship’s launch, so presumably the Philadelphia-based artist had the opportunity to see the completed ship. Interestingly, the masting as depicted in the engraving mirrors the print of a frigate published in the appendix of Capt. Thomas Truxton’s 1794 work titled Remarks, Instructions, and Examples Relating to the Latitude & Longitude, and carries nothing higher than topgallants on the main and fore masts, and only a topsail on the mizzen. Most interesting of all is the depiction of the stern. We can just make out a gallery of two levels separated by a balustrade. A large, almost semi-circular and heavily-carved sternboard unifies the two levels. The quarterdeck bulwarks are planked up, and the poop is surrounded by a high rail. A loose-footed spanker makes room for an ensign staff.

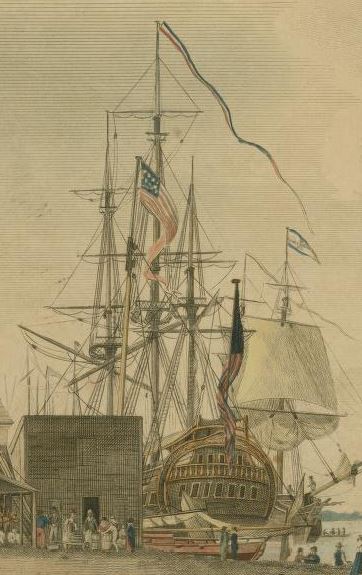

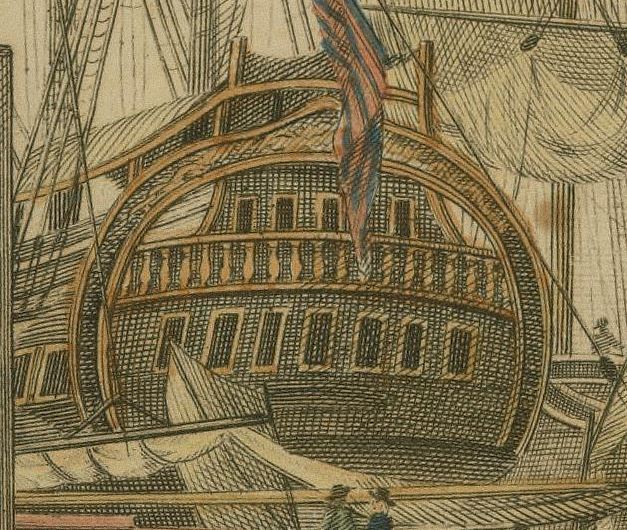

In 1800 William Birch published his The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America; as it Appeared in the Year 1800, Consisting of Twenty Eight Plates. One of the plates is a view of the Arch Street Ferry. In the background, a large ship lies moored to the wharf, looming over the surrounding buildings. This vessel bears a striking similarity to the frigate depicted three years earlier by Thomas Clarke. She carries the same rig and ensign staff. Here, however, we get a much better look at the ship’s stern. We can see the two levels of the stern gallery and the turned balustrade. The sides of the roundhouse exhibit some extreme tumblehome and terminate in posts that support the poop railing. Most remarkable of all is the deeply carved sternboard that seems to almost float free of the structure.

Is this the US frigate United States? We can’t say with absolute certainty, but the fact that both engravings feature a ship with the same overall form is a strong indication that it is. In his other plates, Birch depicted many of the buildings occupied by the Federal Government. Why not depict the Philadelphia-built ship that was the very embodiment of Federalism?

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.