Building 22 in the Charlestown Navy Yard, the red brick and Quincy granite building formerly called the engine house or the pump house, contained the steam engines, boiler room, pumps, and wells for the discharging of water from the Navy Yard’s first naval dry dock, Dry Dock 1.

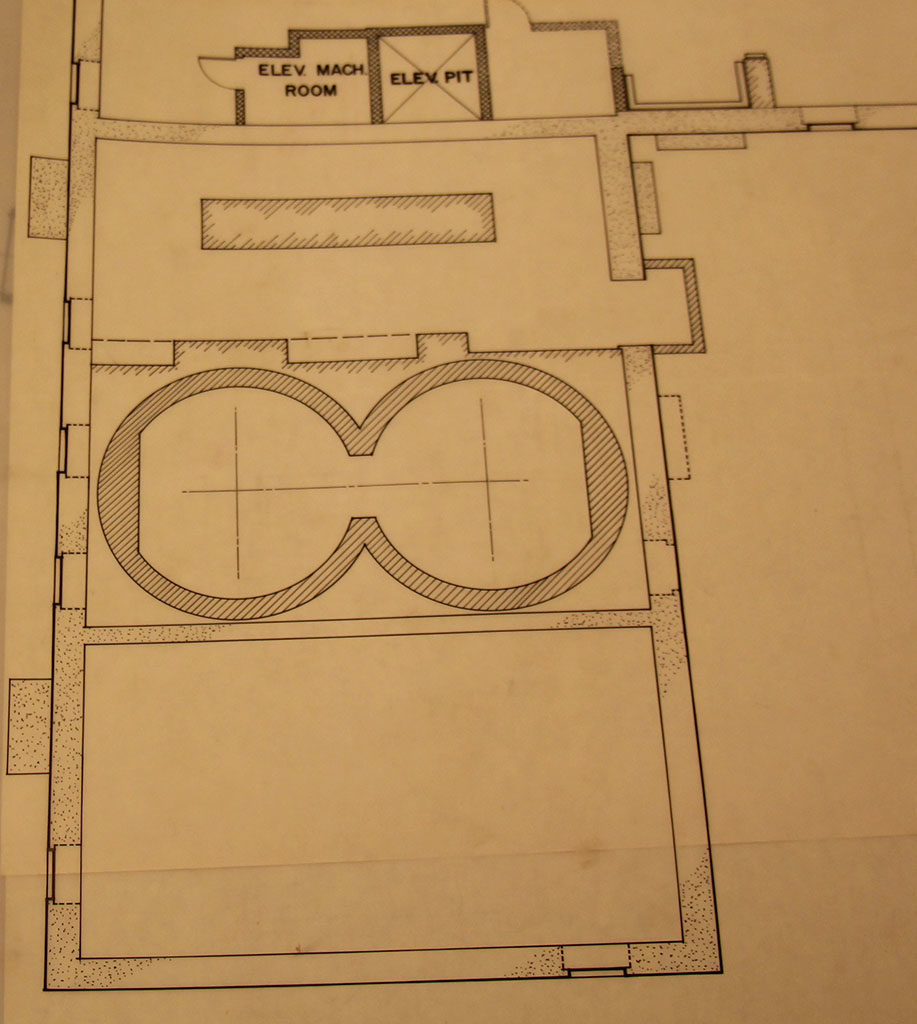

Dry Dock 1 originally held approximately 3.6 million gallons of water and the first pumps were reported to be able to drain the dock in only six hours. The “two great wells,” as described in the 1835 article “Dry Dock at Charlestown,” in the basement of Building 22 were “fourteen and a half feet in diameter, made of brick laid in cement, having the bottom concave like a reversed dome, with a curvature of two feet, the lowest of which is thirty-seven feet below the coping.”1

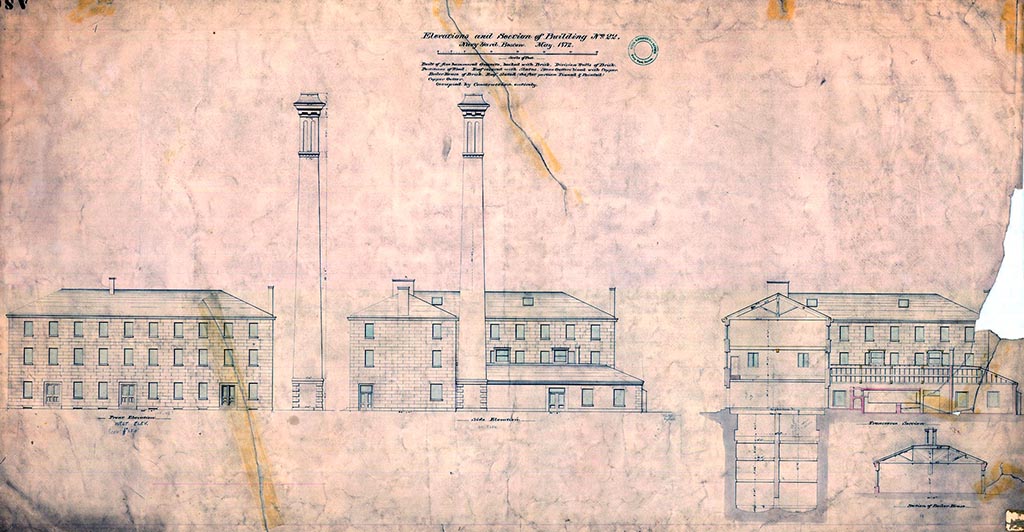

The wells and their depth can clearly be seen in the May 1872 “Elevations and Sections of Building 22.”

Building 22, being an industrial building with many uses – including a block-making shop, a larger boiler house in the attached wing (see the center image in the May 1872 plan showing the one-story boiler house), grind shop, etc. – needed to be as fire proof as possible. The building, although frequently referred to as a “granite” building, is, in fact, a brick building that is faced with dressed granite. Brick is fire proof, whereas granite is not. Although the interior structure is largely constructed with wooden beams, joists, and flooring, there are iron supporting columns and fire doors separating the sections of the building (see photo below). The fire doors are made of sheet iron plates, held together with iron studs, supported on heavy iron hinges that help the doors to swing with relative ease even today. Unlike modern fire doors, which are fire rated according to time and temperature of the blaze, the iron doors in Building 22 would not have presented much of a fire barrier. Note that the door in the photograph does not fit snugly in its opening. Also, most important, iron under intense heat buckles, thereby allowing the fire to pass from one section of the building to another. The intention of the doors was laudable, but not practical.

By the mid-19th century, the Building 22 complex was completed when a one-story brick building was built off the north and east sides of the structure. This relatively small building eventually became the boiler to supply power to the Yard. In 1994, it became the USS Constitution Museum’s theatre.

Another structure, Building 28, was built on the opposite side of 5th Street (actually a short alley between Buildings 22 and 28) in 1849. Originally a one-story brick building, it was used as coal storage for Building 22’s dry dock engines and boilers. This newer building was expanded and altered throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century. In 1995, it was annexed to the USS Constitution Museum, as part of the Museum’s expansion project.

By the 20th century, Building 22 was no longer the engine house for Dry Dock 1. With the opening of Dry Dock 2 (located behind Building 28) in 1906, the de-watering pumps for both dry docks were located in the newly constructed circular pump house on Pier 4. The “engine house” purpose to Building 22 was no longer.

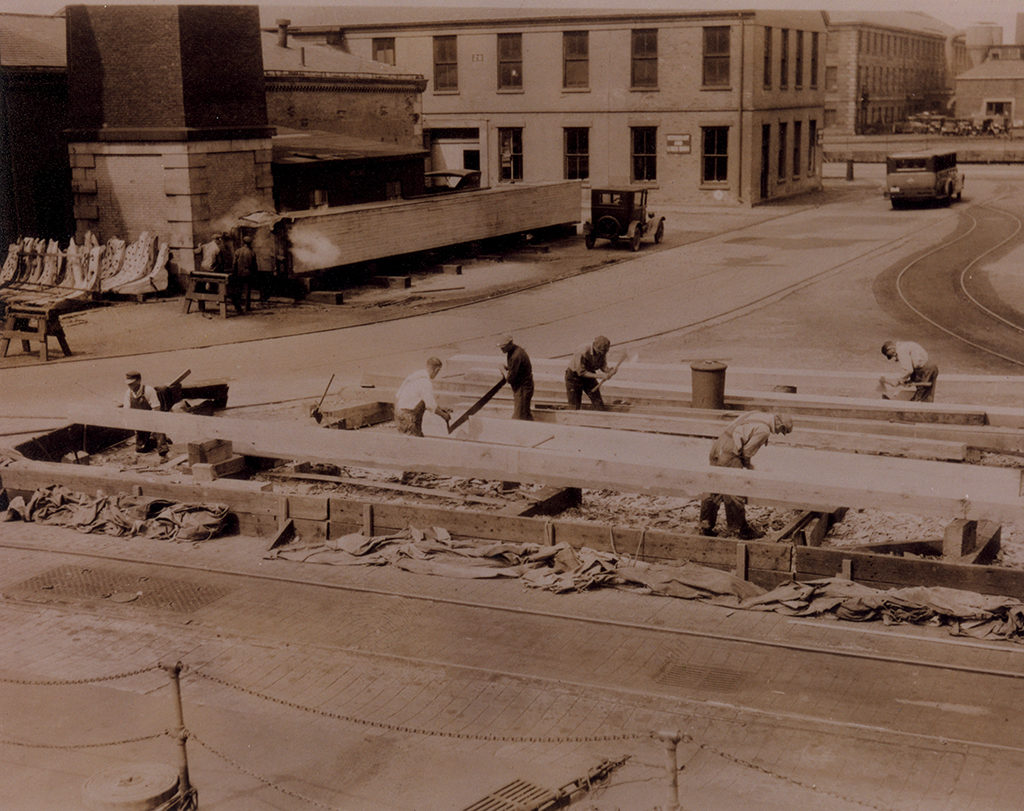

USS Constitution entered Dry Dock 1 on June 16, 1927, for the most significant re-build and restoration up to that point in its long career.

The four-year, nearly $1 million project was supervised by Lieutenant John A. Lord of Bath, Maine. Lord and his staff, including draughtsmen Charles S. Adams, Warren D. Liebmann, and J.C. Gamble, had an office in Building 22. Their office, with its proximity to Dry Dock 1 was a great advantage to them and their work on USS Constitution.

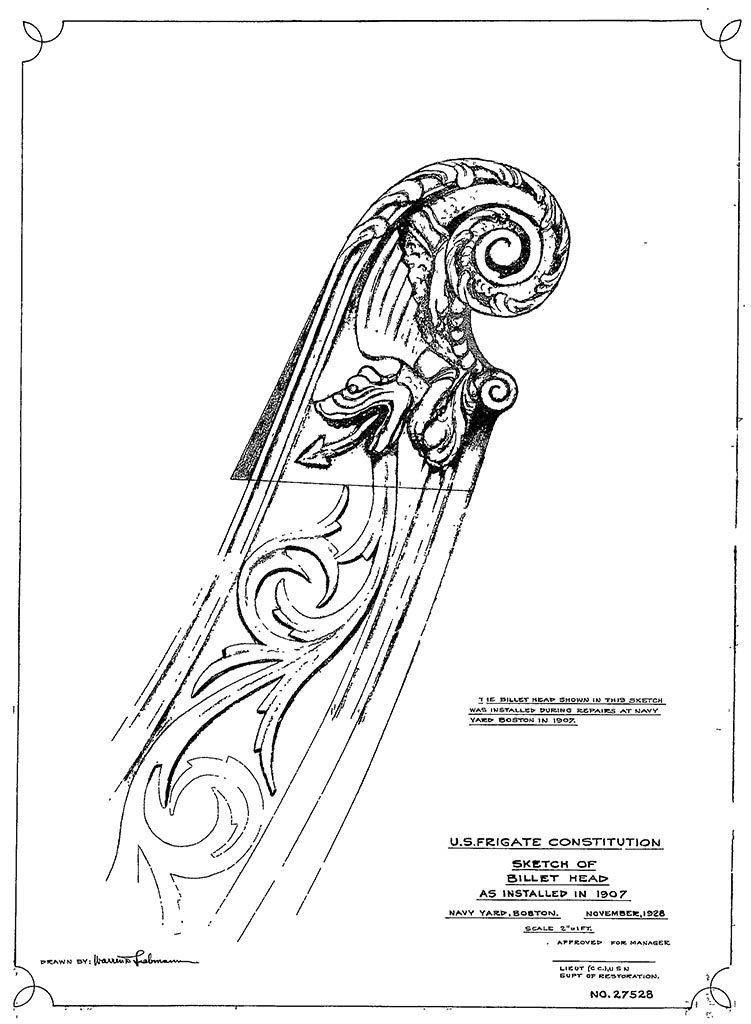

From their Building 22 office, Lord and the draughtsmen re-drew Constitution to a level of detail never seen before. By the time the 1927-1931 restoration was completed, over 300 separate plans had been meticulously hand-drawn. Most of the plans were utilitarian in their execution, such as the sails, while others were of “Old Ironsides” souvenirs which were sold to raise much needed restoration funds. Still other plans documented the ship and were near fine art renderings, like the drawing of the 1906 restoration “dragon” billethead.

In 1974, the Charlestown (or Boston) Navy Yard closed after 174 years of service to the United States Navy. Even before the closure, discussions had been underway for the National Park Service to step in as the new steward for approximately thirty acres of the 150-acre Navy Yard site. As early as 1973, Building 22 had been identified as the best location for the newly incorporated USS Constitution Museum. In January, 1975, the Museum entered into an agreement with the National Park Service and the Navy to occupy the building and convert it into a museum facility.2

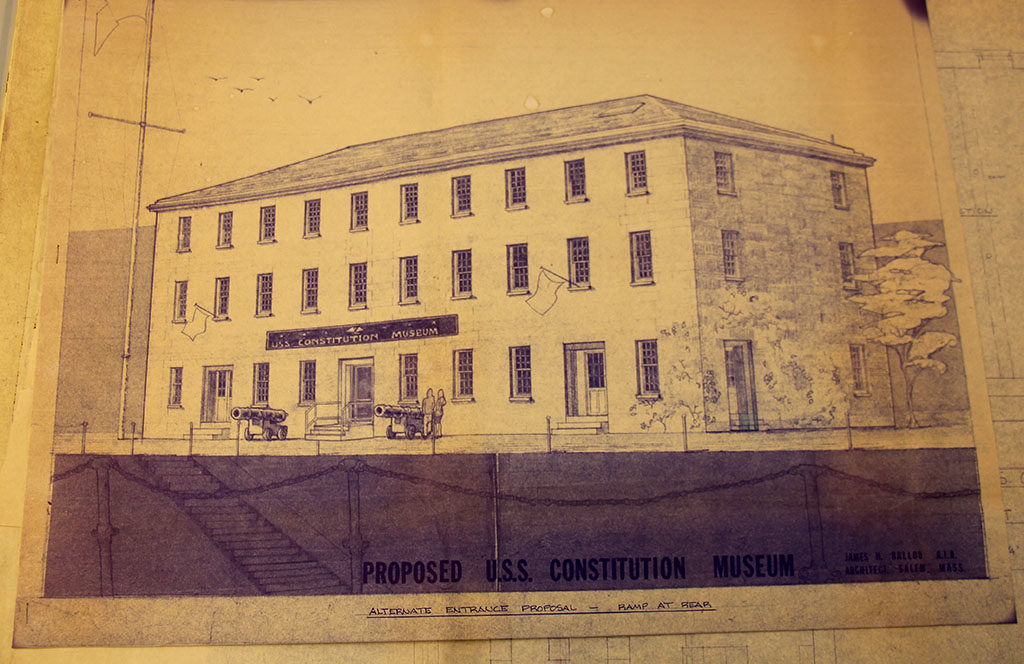

James H. Ballou, an architect from Salem, Massachusetts, was hired to turn the 143-year-old industrial building into a vibrant naval museum. The USS Constitution Museum archives has a number of plans executed by Ballou and two are featured below to show the past and the future of Building 22.

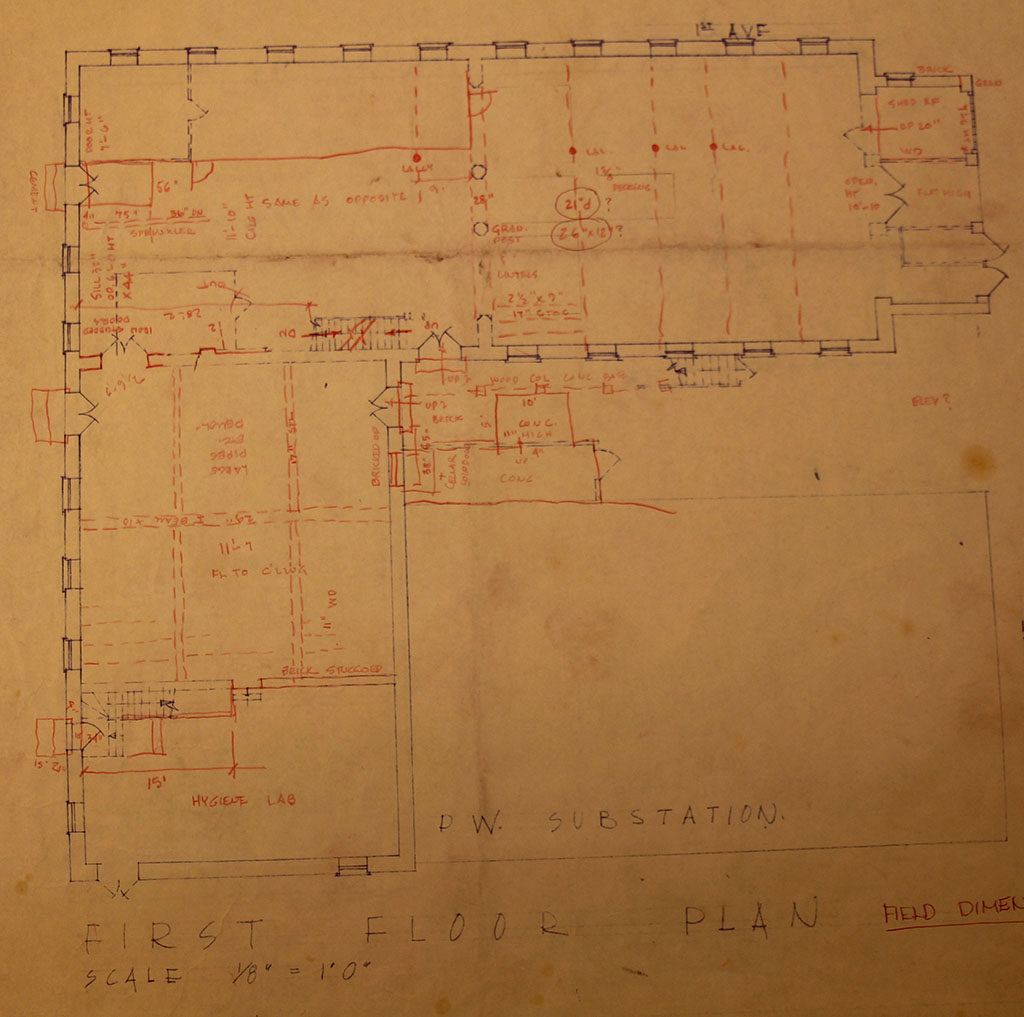

The “Field Dimensions” plan is one of Ballou’s first renderings of Building 22. This roughly detailed plan gives us, today, a sense of what the building looked like inside in 1975. All three sets of front doors were operational, including the one that led to Lt. Lord’s office in 1927 (today this door is an emergency exit). A staircase that led to the upper floors is the approximate location of the elevator. A set of loading dock doors, noted as “bricked up,” were opened and enlarged to become the entrance portal to the 1994 glass corridor connecting Buildings 22 and 28.

Even as late as 1975, remnants of the “engine house’s” original purpose were still evident in the building. Ballou noted the location and archaeological evidence of the “two great wells” in the basement.

The history of Building 22, Dry Dock 1’s “engine house” didn’t stop when the Museum began the renovations in 1975. Part II of “An Engine House Becomes a Museum” showcases the USS Constitution Museum’s history in this iconic building of the Charlestown Navy Yard.

1 American Magazine of Useful Ideas, Vol. 1, Boston, 1835.

2 Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Stephen P. Carlson, Volume 2, 461.

_____

The activity that is the subject of this blog article has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Maritime Heritage Grant program, administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

The Author(s)

Margherita Desy, Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston

Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command

Margherita M. Desy is the Historian for USS Constitution at Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston.

Phaedra Scott

Content Developer, USS Constitution Museum

Phaedra Scott was the Content Developer at the USS Constitution Museum from 2016 to 2017.