“At 2.30 P.M. our wheel was shot entirely away…”

[“Extract from Commodore Bainbridge’s Journal Kept on board the U.S. Frigate Constitution“, The Naval War of 1812, A Documentary History, Volume 1, ed. William Dudley]

William Bainbridge, captain of USS Constitution for her War of 1812 battle against HMS Java, found himself in a very difficult situation only twenty minutes into the almost three and one-half hour engagement with the British frigate. One of Java‘s shot made a direct hit on Constitution‘s double wheel, immediately killing two of the four quartermasters who were steering – Mark Snow and John D. Allen. The two survivors were injured — Peter Woodbury’s left thumb was shot off and William Leonard was slightly wounded, according to the “Bainbridge Battle Bill” in Record Group 45 in the National Archives. Bainbridge, too, received injuries from shrapnel when the shot shattered the wheel and surrounding companionway railings, but he remained on deck for the rest of the battle.

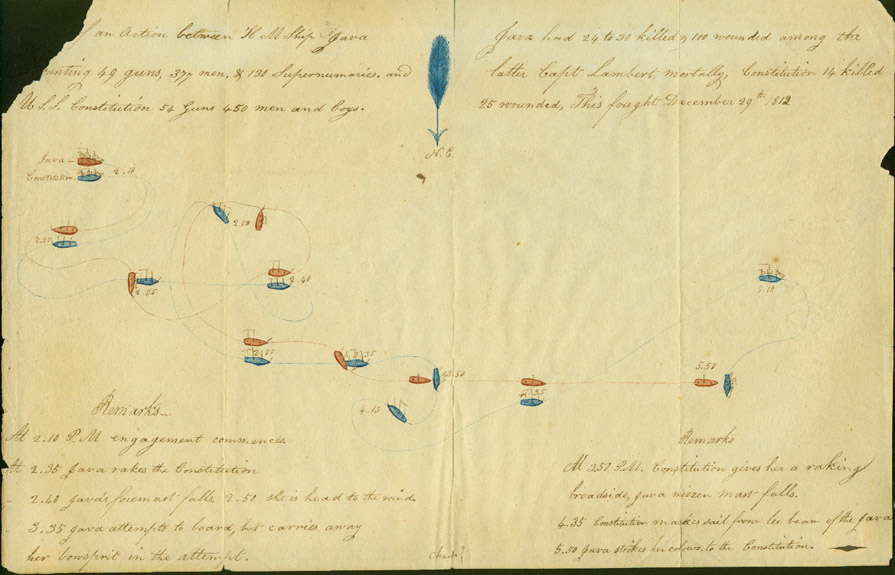

How was Constitution steered for the duration of the battle? Several of her crew were sent to the berth deck, two decks below the spar (upper) deck, where they maneuvered the ship using the iron tiller fitted into the rudder stock as part of the steering gear. Without being able see the battle, the crew handling the tiller were dependent upon a very serious game of “telephone” — where orders were issued, man-to-man, until they reached the tiller crew, who then executed the sailing command. The loss of the wheel appears not to have hampered Constitution‘s success against Java on December 29, 1812, as can be seen in the battle diagram below, drawn by the ship’s Sailing Master, Charles Waldo, after the engagement.

Let’s leave Captain Bainbridge and his crew with their victory over HMS Java and step back a bit further into USS Constitution‘s past to look at her wheel on the quarter deck.

There are no images or descriptions of Constitution‘s original wheel and steering arrangement when she was launched in 1797. However, the 1804 Watch & Quarter Bill for Constitution records only two men as necessary for manning the ship’s wheel. From this information, we can infer that the ship was originally fitted with a single wheel.

When Constitution returned from her 1803 – 1807 Mediterranean cruise — a multi-year deployment to Tripoli and waters around North Africa — the ship underwent repairs in New York between February 1808 and March 1809 that totaled $99,967.76 [A Most Fortunate Ship, Tyrone G. Martin, 128]. In 1809, Midshipman John M. Funck noted in his Watch & Quarter Bill that four men were needed at the ship’s wheel, indicating that Constitution was fitted with a double wheel during the 1808-1809 work in New York.

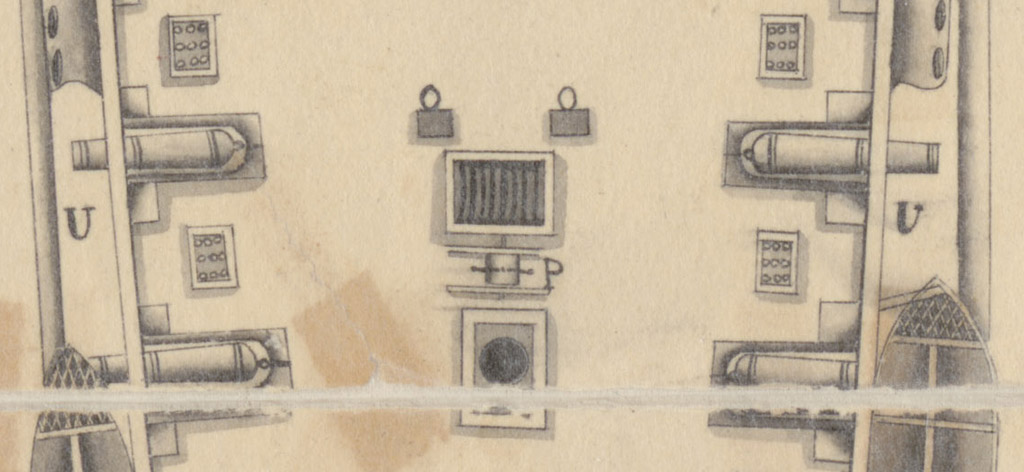

A plan of USS United States, drawn after the War of 1812, provides a sense of what Constitution‘s double wheel and surrounding ship structure and equipment may have looked like at that period.

During the War of 1812, when the battle against HMS Java was over, Captain Bainbridge received the surrender of his opponent’s ship from the first lieutenant, Henry Ducie Chads, as Captain Henry Lambert lay mortally wounded below. Java was too badly damaged to be saved, and was therefore destroyed. Before her magazine was lit, the wounded and prisoners of war were put on board Constitution and the dead were buried at sea. Afterwards, the Java prisoners were left at St. Salvador, Brazil, and it was there that Lambert died and was buried. Constitution sailed for home, arriving in Boston on February 15, 1813.

Despite her victory, Constitution had sustained a great deal of battle damage. Within days of returning to Boston, workers began making repairs and replacing worn and rotten parts of the ship. Java‘s wheel was not aboard Constitution, contrary to popular myth. The tally of monies spent by the U.S. Navy notes that on August 18, 1813, T. & R. Howe were paid $45.00 for “Making Stearing [sic] Wheel”. And, on September 10, John Fuller was paid 50 cents for “trucking Constitutions Wheel &c fr[om] Howes to [Constitution]”. [RG 217, 4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, Alphabetical Series, Box 38, National Archives]

Years later, in 1839, Constitution‘s log notes that a new wheel was received aboard the ship. It is not known for certain whether this 1839 wheel replaced the 1813 wheel or another wheel was installed between 1813 and 1839. Constitution underwent several refits and rebuilds from 1840 to 1871, a time when the ship sailed around the world (1844-1846) and then transitioned from front-line warship to training vessel. As of this writing, none of the extant records indicate that she received another new wheel.

Between 1872 and 1877, Constitution underwent a lengthy rebuild at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. There is a story that, during this period, Constitution‘s wheel was removed and placed aboard USS Potomac, which had been sold to a ship breaker from New York. Potomac didn’t have a wheel, and Constitution‘s wheel, according to the story, was appropriated so Potomac could be steered to the breaker’s yard. Unfortunately, this story cannot be verified at this time with the extant Navy documentation.

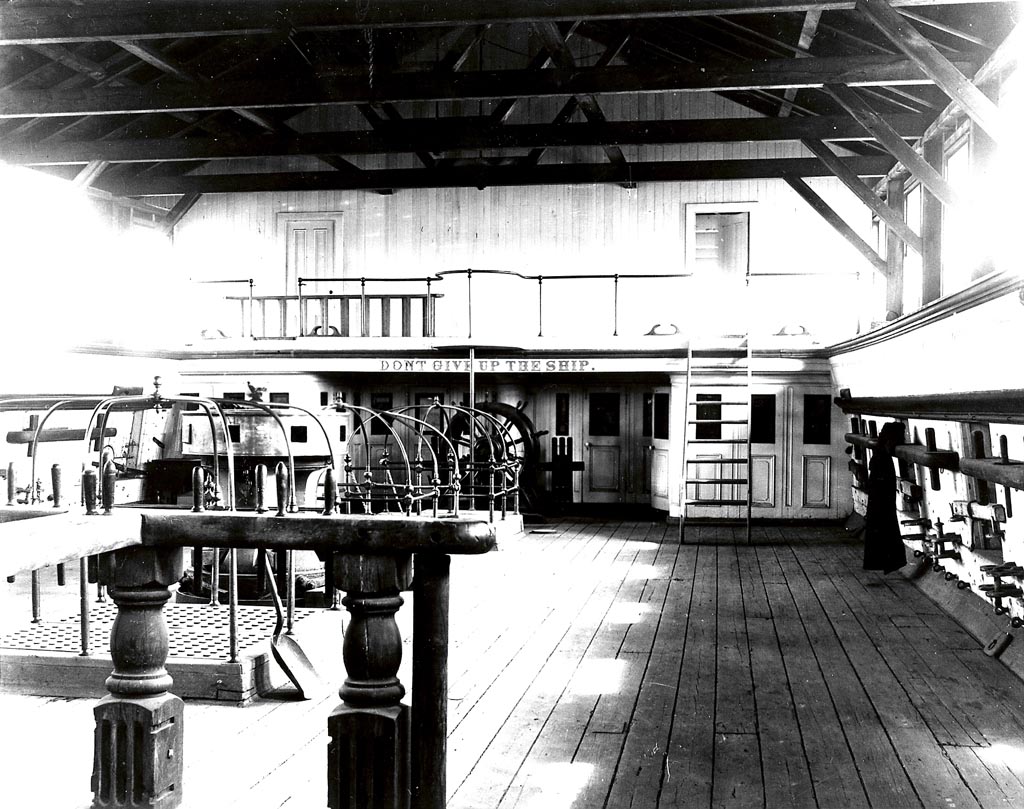

Constitution was obviously fitted with a wheel after the Philadelphia rebuild. It is not known whether it was her own wheel that was temporarily removed for the rebuilding (and not placed aboard Potomac, as per the unverifiable story), or a newly constructed wheel. However, this Philadelphia rebuild wheel appears in the first known photograph of any of Constitution‘s wheels. The image, shown below, is circa 1895, when “Old Ironsides” was turned into a receiving ship with a large barn-like structure built over her spar deck. Because of the double-height interior with the barn, an upper deck was built over the stern. This deck covered the wheel, which can be seen under Captain James Lawrence’s immortal words, “Don’t Give Up the Ship”.

“Old Ironsides” returned to Boston on September 20, 1897, one month before her 100th anniversary. The Philadelphia rebuild wheel was still aboard the ship, and was used to steer Constitution on her journey, under tow, from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard to the Charlestown Navy Yard. The wheel remained aboard the ship through her first official restoration, which took place between 1906 and 1907.

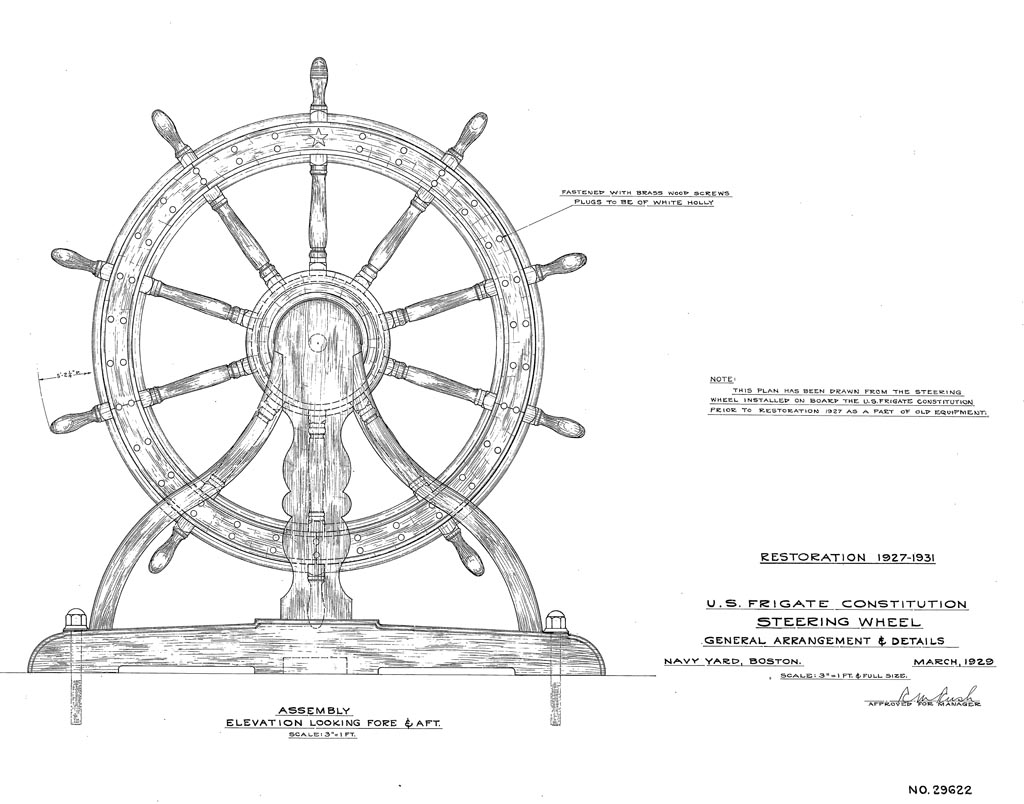

A new double wheel was manufactured for Constitution during her 1927 – 1931 restoration in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Hyde Windlass Company, in Bath, Maine, was sent a set of plans, titled “U.S. Frigate Constitution Steering Wheel”, drawn by naval draftsman Warren D. Liebman (shown below). Liebman based the design of the new wheel upon the Philadelphia rebuild wheel that was aboard Constitution before the 1927 restoration. The specifications called for the wheels and the supporting yokes to be made of cherry, and the drum, which connects the two wheels, to be made of maple.

The Hyde Windlass Company wheel was installed by the spring of 1931, as the ship received her final outfitting and rigging for her upcoming National Cruise. The newly appointed captain of the ship, Commander Louis J. Gulliver, posed at the wheel with Lieutenant John A. Lord, Supervisor of the 1927 restoration, for a May 19, 1931 photograph (shown below). Less than two months later, on July 1, 1931, Constitution was re-commissioned. She departed the next day, July 2, for a three-year, three-coast tour of the United States.

What became of the 1870s Philadelphia rebuild double steering wheel? One photo from the 1960s shows it displayed on Constitution‘s berth deck.

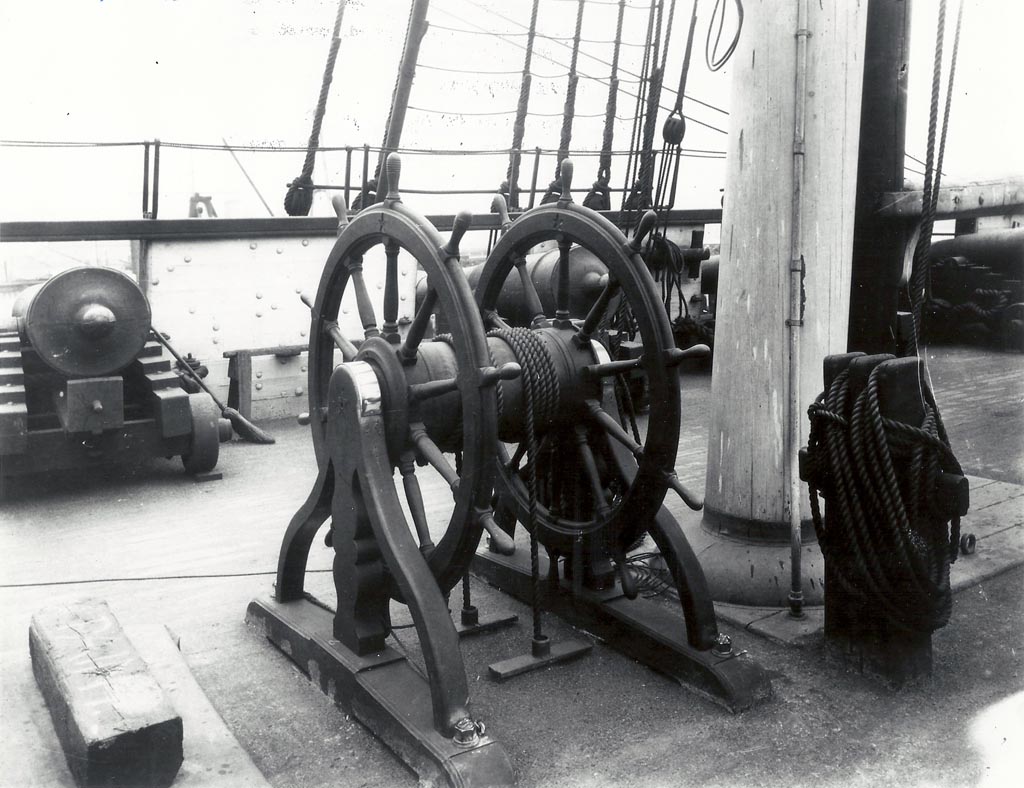

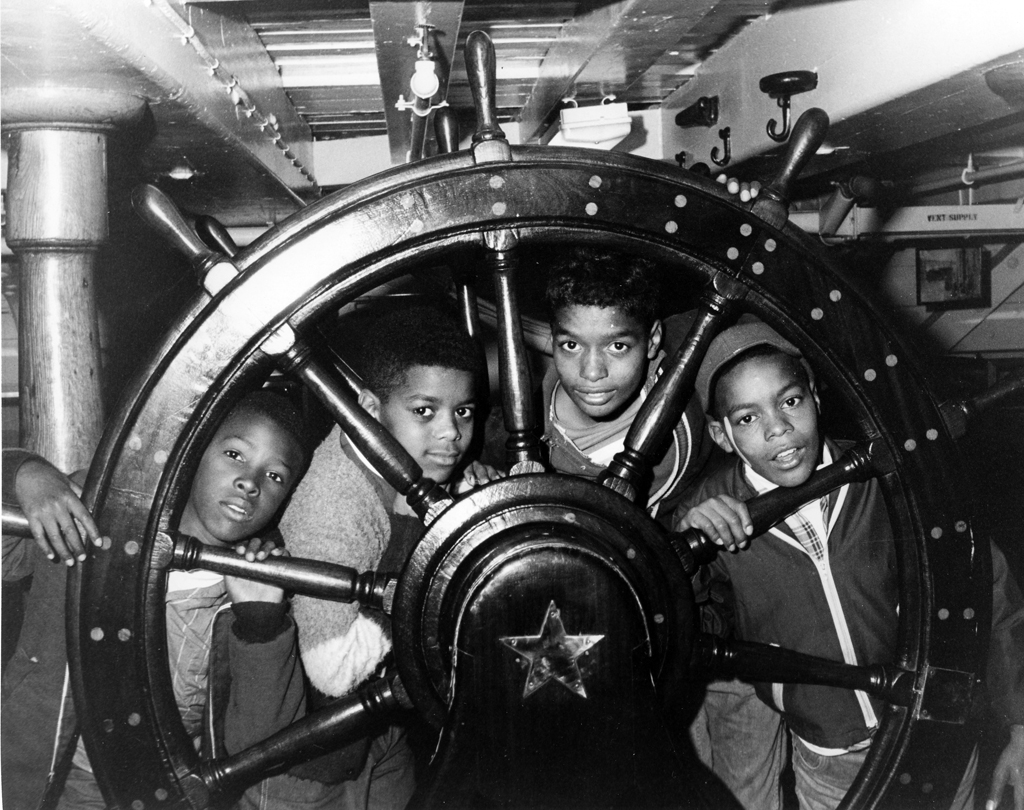

In 1978, the USS Constitution Maintenance & Repair division (precursor to the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston) removed the 1929 Hyde Windlass double wheel from the ship and loaned it to the recently opened USS Constitution Museum in the Charlestown Navy Yard. The wheel, which had seen millions of visitors to “Old Ironsides” during the ship’s 1930s National Cruise and later while on display in the Navy Yard, played host to many more thousands of visitors, especially children, as part of the “Life At Sea” exhibit at the USS Constitution Museum. During this time, the 1870s Philadelphia rebuild wheel was removed from the berth deck and placed in its former position on the quarter deck, once again connected to Constitution‘s steering gear (shown below).

In late 1987, the Philadelphia rebuild wheel, which had been aboard the ship for nearly ten years, was removed for refurbishment. According to Don Turner, production supervisor of USS Constitution‘s restorations, “As soon as repairs were initiated the seriousness of the decay throughout the piece was noted. The decision was made to continue repairs to the old helm & send [the] finished product to [the Navy] Museum at the Washington Navy Yard & build a new helm for installation aboard the ship.” [Documentation notes by Don Turner dated February 19, 1988, NHHC Detachment Boston Historian’s files]. A new wheel was constructed over the winter of 1987 to 1988. By the spring of 1988, the 1870s wheel had been repaired and sent to the National Museum of the United States Navy, where it can still be seen on display today.

The new wheel installed in 1988 is currently still in use on USS Constitution. Like the other wheels before it, the 1988 wheel has seen some historic moments, none more so than when “Old Ironsides” sailed for the first time in 116 years under her own power on July 21, 1997. This historic sail commemorated the ship’s 200th anniversary. On board for the event were many military and government dignitaries and a few celebrities, including retired CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, himself an accomplished sailor. For a brief moment, Cronkite took a trick at Constitution‘s wheel as the ship glided gracefully along under her battle sail configuration of three topsails, two jibs, and spanker.

Every autumn Constitution‘s wheel is removed and repaired over the winter by NHHC Detachment Boston ship restorers. The past two winters were no exception, even with the ship in dry dock. After receiving annual repairs and new coats of heavy spar varnish, the wheel is re-installed on Constitution‘s quarter deck each spring.

In 2017, the newly varnished double wheel and its supporting yoke were lifted on board Constitution on a brilliant April afternoon.

The freshly varnished and re-installed double wheel awaits its next adventure as “Old Ironsides'” first 21st century dry docking comes to an end on July 23, 2017 and the ship is refloated into Boston Harbor!

The activity that is the subject of this blog article has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Maritime Heritage Grant program, administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

The Author(s)

Margherita Desy, Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston

Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command

Margherita M. Desy is the Historian for USS Constitution at Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston.