In October 2017, the USS Constitution Museum hosted a reunion of Constitution crew who had participated in sailing the ship to Marblehead, Massachusetts, for its 200th anniversary in 1997. That event 20 years ago was the last time Constitution left Boston harbor. The voyage followed a four-year restoration that had strengthened the hull enough to allow consideration of sailing the ship, something that had not been done since the 1880s.

Getting underway under sail on such a huge, demanding vessel was a daunting undertaking for the 1997 crew and their commanding officer, Commander Michael Beck. The ship needed to be capable of withstanding the force of the sails pulling on the rigging and hull, and the crew had to be increased in number and properly trained to manage those forces. These were tasks that Constitution’s 19th-century sailing masters were well acquainted with and equally attentive to. Like all sailing ships, Constitution’s numerous different sails allowed the ship to operate in rapidly changing and often dangerous weather conditions. But setting, striking, and adjusting those sails demanded a choreography of crew work from hundreds of sailors for whom these tasks became second nature with daily practice.The Watch Quarter and Station Bill was the key to that choreography. Created by one of the officers, the bill assigned every member of the crew to specific teams and tasks in specific situations. Similar station bills are still required today of both navy and commercial ships.

First Lieutenant Peter Turner’s Watch Quarter and Station bill from 1839 provides a window into what it takes to actively sail a ship with such a large rig, and helps explain why it was considered such a substantive undertaking in 1997. Comparing Turner’s bill to the Watch Quarter and Station bill created for the 1997 sail highlights the challenges the modern crew faced. Turner had 450 sailors to distribute to different sail-handling tasks. While the 1997 crew was going to set far fewer sails under much more controlled conditions, they had only about 120 crew to do it, and none of them had the experience or skills that were common to Constitution’s 19th-century crew.

“We didn’t know how to sail a ship like this,” CDR Michael Beck recalled in an oral history recorded during the recent reunion. “We were tour guides.”

Beck said he recognized that the ship’s success as an active warship had depended on captains who “were not only competent but they trained the crew to a level of professionalism that outgunned and defeated every foe.”

To train his crew in the necessary tasks, Beck enlisted the support of the United States Coast Guard (USCG)’s sail training ship Eagle and the privately-run tall ship Bounty. To ensure that the crew could complete their tasks effectively underway, Beck and his senior officers organized the crew into teams similar to those of the 19th century, only much smaller.

During Constitution’s active sailing career, the crew was largely divided into two watches, designated “Starboard” and “Larboard.” The watches took turns operating the ship around the clock when it was under sail. In any situation in which more than the working watch were required, all hands could be called. A number of crew members who performed specific roles on board — such as carpenter, cook, and surgeon — were exempted from standing a watch (and thus known as “Idlers”), but could also be called in time of need. In battle, the entire crew were called to quarters and a different system of assignments were implemented.

For basic sailing operations, each watch was sub-divided into six teams or stations, with each team generally responsible for handling sails and tasks around a specific area of the ship. The Marines on board could also be assigned to sailing tasks, and the warrant officers were also broken up by watch.

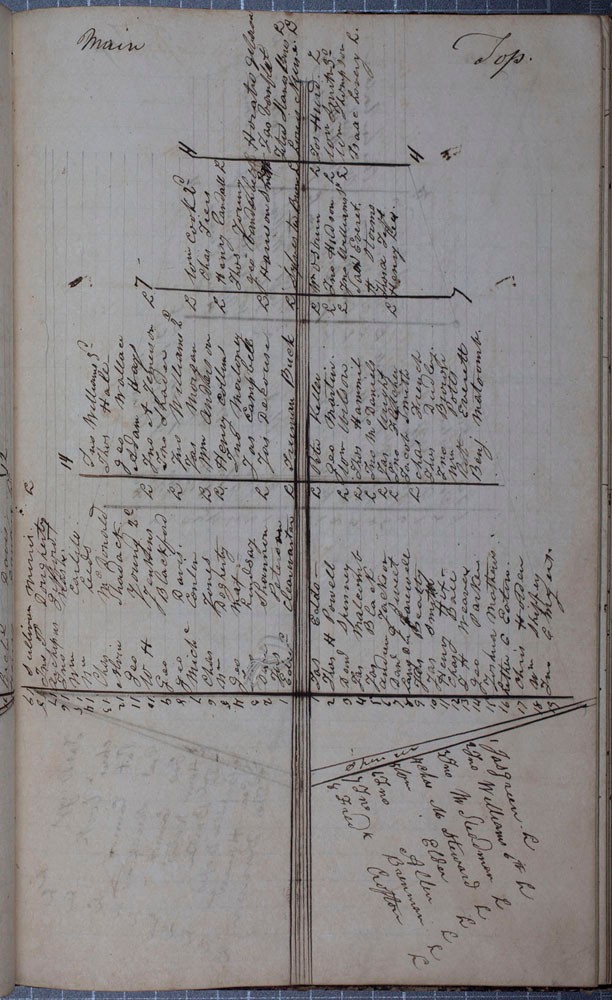

Like others before and after him, Turner produced lists of which crew were assigned to which watches and stations, but also provided diagrams of the masts to show where each of the topmen would be stationed for loosing or furling sails. Many of those crew would usually shift back to the deck to assist in hauling on lines during the more laborious tasks, such as setting sail or tacking the ship.

The sheer numbers of crew assigned to each station and to specific tasks at each station demonstrates just how much physical labor was required to safely harness enough wind to make the ship move effectively. For example, as many as 40 crew were assigned just to manning the main topsail yard.

|

1839 Crew Station assignments |

# on Starb’d watch |

# on Larb’d watch |

1997 Crew Station assignments |

# |

| Fore topmen | 29 | 29 | Foremast | 31 |

| Main topmen | 30 | 30 | Mainmast | 37 |

| Mizzen topmen | 25 | 25 | Mizzenmast | 31 |

| Afterguard | 63 | 63 | Helm | 2 |

| Idlers | 16 | 16 | Deck Officers | 3 |

| Marines | 20 | 20 | Jibsails | 18 |

| Boatswains Mates | 2 | 2(3) | ||

| Quartermasters | 3 | 4 | ||

| Quarter gunners | 6 | 6 |

The small number of crew and their relative inexperience made the process of setting sails far slower than would have been considered feasible or safe in Turner’s time and circumstances. Turner’s station bill includes diagrams of not only which crew were assigned to work in the rigging, but which yards and sides of the yards they were assigned to. He also provided detailed directions on each team’s order of tasks, both in the rigging and on deck. Once the topmen unfurled sails, most would quickly return to the deck to assist with hauling on the lines that actually set the sails. During a cruise, these tasks were honed with practice every day and night, as the ship adjusted its sail plan to the ever-changing weather conditions and contacts with other ships.

The 1997 crew followed a similar pattern of crew assignments. But, with only one square sail being set on each mast, far fewer lines had to be handled at once. With the extensive safety measures dictating the conditions during the planned sail, Beck’s crew could also be reasonably sure they wouldn’t have to rush to respond to an unexpected squall or enemy contact – luxuries Turner’s crew didn’t have.

Beck and his Command Master Chief Joe Wilson divided the navy crew into three teams by mast. According to the Watch Quarter Station Bill from the 1997 sail, there were 37 crew assigned to the mainmast, 31 assigned to the foremast, and 31 to the mizzen. The 18 midshipmen who had joined from the Naval Academy were largely assigned to manning the two headsails set on the bowsprit. The NHHC crew were distributed throughout the rig and the deck. The crew setting and furling the topsails started from scratch learning to climb the rigging and furl and unfurl sails – tasks that topmen on Turner’s crew would have already been familiar with.

To do that, Beck’s crew practiced climbing Constitution while it was docked in Charlestown. To get the experience of regularly climbing underway, they joined the USCG bark Eagle on a multi-day voyage from Mayport, Florida, to New London, Connecticut, in the fall of 1996. To learn the steps of making sail evolutions, the crew joined the tall ship Bounty for day sails in Boston Harbor and for a passages from New York to Fall River, Massachusetts, and Fall River to Boston. During the Bounty sails, the crew were able to participate in maneuvering the ship relative to the wind, learning what it meant to tack, wear, and steer by the wind. For Constitution‘s young crew of navy sailors, many of whom had never been to sea before on any type of ship, much less a square-rigged sailing ship, the training experiences pushed them to hone new skills.

After the Eagle voyage, CDR Beck asked the crew to write down what they had learned from the voyage. Beck donated the resulting essays to the USS Constitution Museum in 2017. They provide an insight into the exhilaration of sailing a square-rigged vessel.

“Climbing the yards in port took little to no effort,” wrote James J. Mueller. “But underway in the rain with a 10 degree list was nerve-wracking at first, but almost insanely fun after getting used to it. I most enjoyed being on the helm because it was up to me to keep us on course.”

Though Mueller and his fellow sailors had only a taste of the skills that their 19th-century predecessors developed over long careers under sail, Turner and his crew would certainly have appreciated that recognition of the challenges of sailing a ship like “Old Ironsides.”

_____

The activity that is the subject of this blog article has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Maritime Heritage Grant program, administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.