When Ruby-Ann Litinsky applied for a press pass to join USS Constitution’s turnaround cruise in Boston Harbor, she must have known she would be denied.

After all, she is a woman. And in 1971, when Litinsky filed her request, women were not allowed on “Old Ironsides” when it left the dock for its turnaround cruises. Constitution‘s officers and crew were men, the guests were men, and the invited reporters were men.

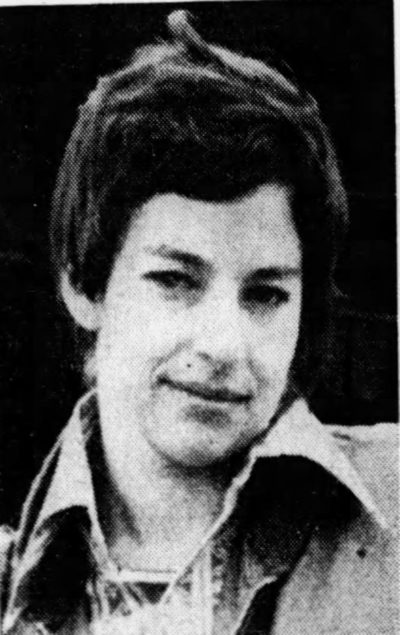

At the time, 31-year-old Litinsky was a reporter for the Peabody Times, a local newspaper in a suburb north of Boston. After being refused a press pass as a woman, Litinsky decided to pursue an alternate means of joining the cruise on Constitution. On June 23, the day of the turnaround, she disguised herself as a man and made her way to the ship to join the sail. Rather than attempting to acquire a press pass as a man, she figured she could simply sneak on board disguised as one. She was accompanied by Peabody Times photographer Alain Jehlen.

That Litinsky was rebuffed for being female, and that she reasonably thought she could sneak aboard disguised as a man anyway, are reflections of the era in which this story unfolded. In 1971, the women’s liberation movement was reaching its peak in the United States, and women were demanding inclusion in a huge swath of American society that remained exclusively male by force of both law and tradition. Up until that point, it appears there was no challenge to the navy’s assertion that Constitution‘s underways were male-only events. Previous years’ press coverage made no reference to the absence of women. The sole exception is a one-line reminder at the end of a 1969 women’s column in the Boston Globe about people in town for a cruise: “It’s men only, girls.”1

At the same time, security surrounding the ship and the turnaround event in 1971 was minimal by today’s standards. The threat of terrorism had yet to become a major concern at sites like USS Constitution. Although the Charlestown Navy Yard, where Constitution is docked, was still an active shipyard, access to the ship was largely unfettered.

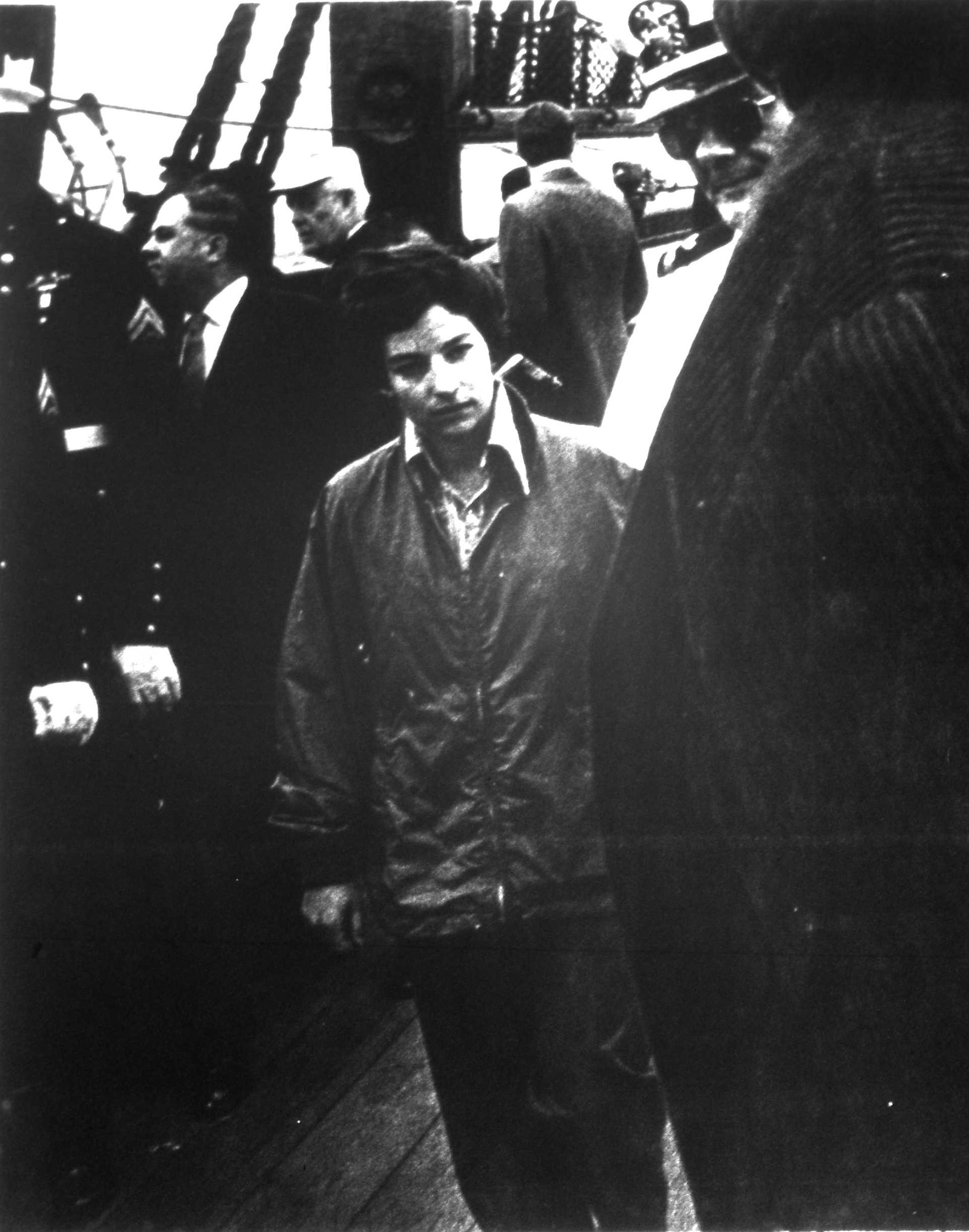

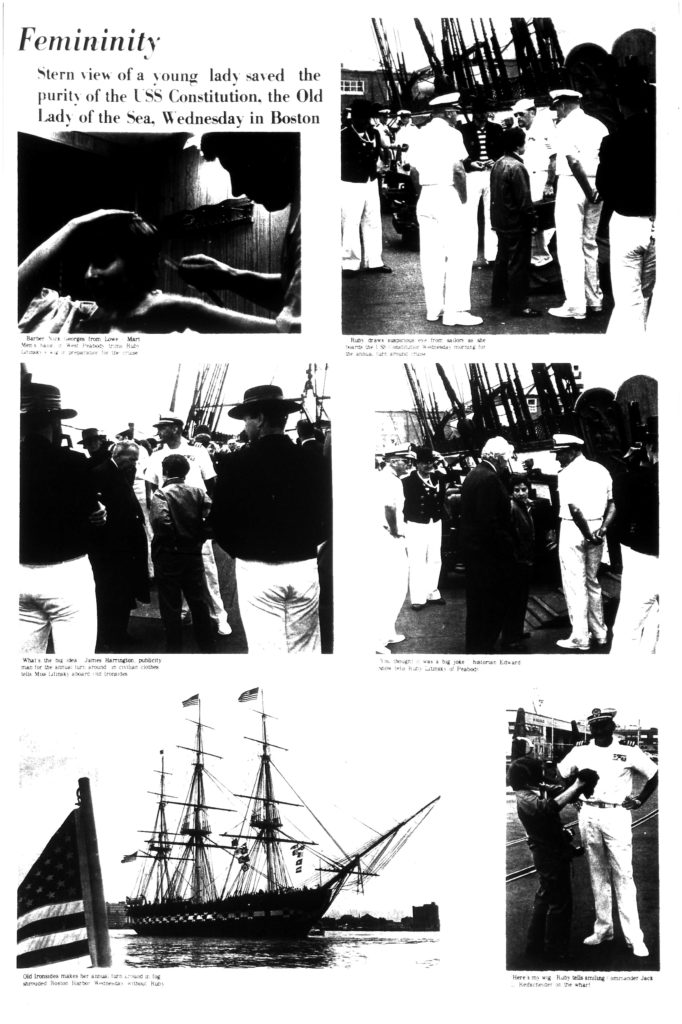

In her story, published in the Peabody Times the day after the turnaround, Litinsky wrote that she was attempting to become the first woman to join the cruise.2 She bought a wig and had it trimmed by a barber to resemble a typical men’s hairstyle. Dressed in trousers, a collared shirt, and windbreaker jacket, she went to the Charlestown Navy Yard to board the ship. At five feet tall, her stature did not make it easy to blend into a crowd of mostly taller men, but she still managed to make it past the two Marine guards on the gangway and onto the ship.

It was there that the ship’s captain, Commander Jack L. Reifschneider, noticed Litinsky and eventually stopped her.

“When I saw you coming up the gangplank, your walk looked funny. Then I looked at your facial features. And when I watched you walking away, from the back, I could tell you were all girl,” Litinsky quoted Reifschneider as telling her.3

According to Litinsky, Reifschneider kept repeating to her that women were not allowed because “we don’t have facilities for them.”

“I won’t need facilities for a two-hour trip,” Litinsky replied.

The navy press officer, Jim Harrington, told her that in order “to save us all embarrassment” and “prevent any incidents,” she would have to leave the ship. She reluctantly did and relocated to a Coast Guard boat that was serving as a supplemental press boat for the turnaround.

Litinsky’s front page story, with the headline “Stern side view saves Old Ironsides,” recounted her failed effort to stay aboard. A full page of Jehlen’s photographs showed a barber trimming her male wig (top left), the aftermath of her being caught (top right and center), and Litinsky showing her wig to an amused-looking Commander Reifschneider (bottom right).

The Boston Globe also published an article with photos of her effort, and that story was picked up by newspapers across the nation. Many of the headlines referenced the popular notion that sailors thought a woman on board was bad luck, or highlighted the navy’s insistence on adhering to tradition. The Globe’s own headline was “Stern view saves Ironsides’ purity.”4

As part of her coverage in the Peabody Times, Litinsky contacted the office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, about lifting the ban on women. A spokesman told her the admiral “will look into” it.

The next summer, without any special announcement or official notice, the navy began allowing women on turnaround cruises. On June 14, 1972, at least three dozen women were aboard for a turnaround cruise, including several young girls who were part of invited school groups from around the country.5

This change may have been influenced by Litinsky’s publicity the previous year, or was maybe in response to broader pressure from the women’s liberation movement. At the time, however, Rear Admiral Joseph C. Wylie, commandant of the First Naval District in the Charlestown Navy Yard, insisted the women’s liberation movement had not influenced the decision. He told The Boston Globe merely that, “The Navy’s always modern…. The Navy is always keeping up with the times.”6

Nearly 15 years later, the first female sailor joined the ranks of USS Constitution’s crew. In November 1986, Yeoman Second Class Rosemarie Lanam stepped aboard. Ten years after that, in 1996, Lieutenant Commander Claire V. Bloom joined the ship as Executive Officer, becoming the first female officer assigned to Constitution.

In 2020, 20 female sailors are serving as part of USS Constitution’s 80-member crew. In January 2020, 24 years after Lieutenant Commander Bloom, Lieutenant Christina Carson joined the ship as operations officer, becoming the second female commissioned officer to serve on Constitution.

Ruby-Ann Litinsky Madden died at age 81 on June 3, 2022 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

[1] Marjorie Sherman, “Navy Leaguers honor new chief,” Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), June 26, 1969.

[2] Ruby Litinsky, “Stern side view saves Old Ironsides,” Peabody Times (Peabody, Massachusetts), June 24, 1971.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lucinda Smith, “Stern view saves Old Ironsides’ purity,” Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), June 24, 1971.

[5] Peter Cowan, “Now women man Old Ironsides,” Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts), June 15, 1972.

[6] Ibid.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.