In 1806, on the Unkechaug land of Poospatuck on Long Island, New York, Dorothea Smith married William Cooper, one of the Unkechaug chiefs. Like many in the small, tight-knit community, William worked for one of the white families who owned farms nearby, the Robert family. Dorothea, who went by Dolly, was working at the same homestead when they married. Dolly’s birthdate is unknown, but she may have been between 14 and 20 years old at the time.

Their marriage was cut short just six years later when William, then serving as an ordinary seaman and a sponger for the no. 9 carronade on USS Constitution, succumbed to his injuries in the battle with HMS Java. For Dolly, losing her husband and becoming a young widow made an already difficult life even harder. The couple had two young daughters, Charlotte and Frances, and Dolly was struggling to survive on her salary as a household servant.

At the time of his death, William had been away on merchant and navy ships for at least two years. He had fled to sea after falling in debt to one of his employers, a landowner named General John Smith. William was a victim of a lay system in which employers deducted the cost of food and goods from the income they paid to laborers. This abusive system often left the most vulnerable workers hopelessly in debt to their employers. While at sea on a merchant ship, William was pressed into the British Royal Navy. The British ship, HMS Defence, later sank off the coast of Denmark, and news of William’s demise in that wreck reached Dolly back home. William, it turns out, had escaped from the British ship prior to its sinking. He boarded another U.S. Navy ship in Europe before eventually joining USS Constitution’s crew at Boston. It was then that William wrote to Dolly with the news that he was alive and would eventually return home. Just a couple months later, William became one of the nine Americans killed aboard Constitution on December 29, 1812.

Now faced with the certainty that her husband would never return, Dolly began an arduous effort to claim the benefits due her as the widow of a U.S. Navy sailor killed in battle. William had earned a portion of the prize money for Constitution‘s victories over HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, but Dolly initially saw little of those earnings. When John Smith, William’s former employer on Long Island, learned of William’s death, he filed a claim in the local court for outstanding debts. As a result, William’s prize money and back wages were paid to John Smith instead of Dolly. After keeping the portion he claimed was owed him, John Smith sent the remaining money to Dolly and her two children.

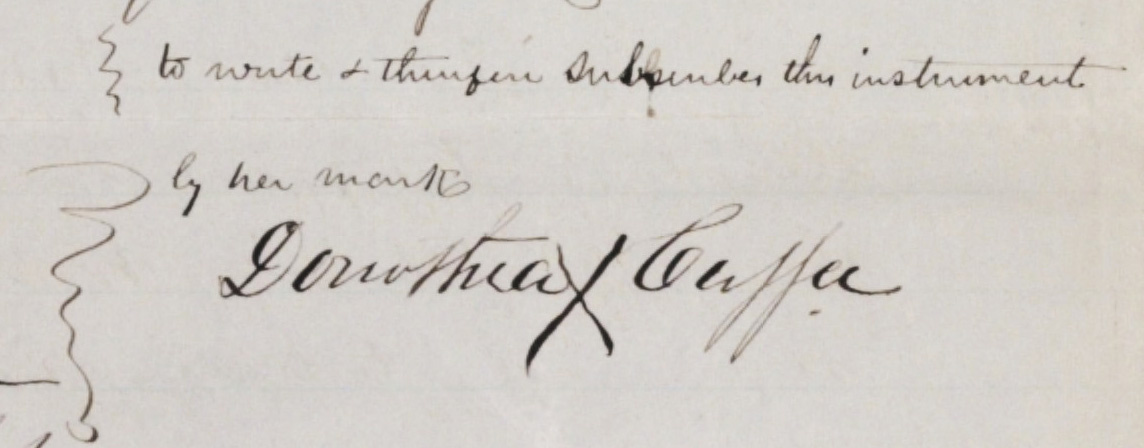

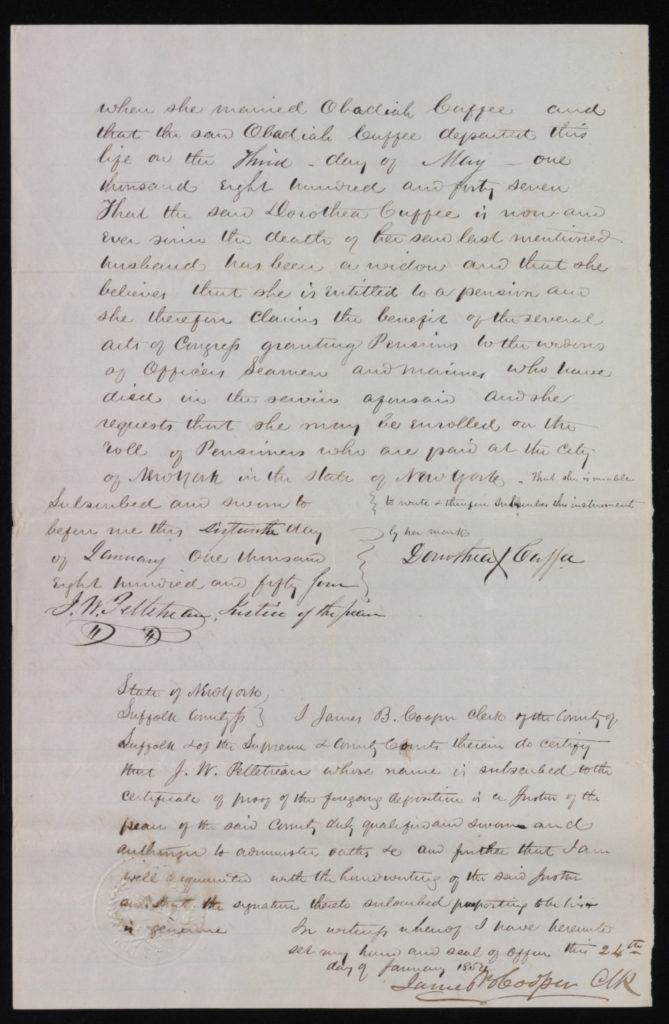

In addition to what remained of the prize money and back wages, Dolly was due a navy pension for William’s service. She turned to Daniel Robert Jr., a son of the Robert family for whom she and William had worked, and whom Dolly had helped raise. Daniel appealed to the U.S. Navy on Dolly’s behalf to secure the pension she was owed. It was a tenuous application. Dolly had no written certificate to prove she and William were married, and she was illiterate. Robert himself testified to her marriage. After numerous appeals, the Naval Pension Office finally issued Dolly a certificate in 1819 for $6 per month, payable twice a year and good for ten years from the date of William’s death. By the time the certificate expired in 1822, Daniel recorded Dolly’s total receipt as $716. On Dolly’s behalf, he requested and was granted a five-year extension under new pension legislation in 1825.

She also became a respected matriarch of the Unkechaug community, marrying two more times to Unkechaug men, both of whom she outlived. Sometime around October 1826, Dolly married Adam Brewster, who worked on a farm near Poospatuck owned by Josiah Smith. In 1828, Dolly and Adam had a son, Nelson. According to local records uncovered by Strong, the Brewsters did relatively well for a little while, but in 1829 Adam drowned while fishing on the Great South Bay.

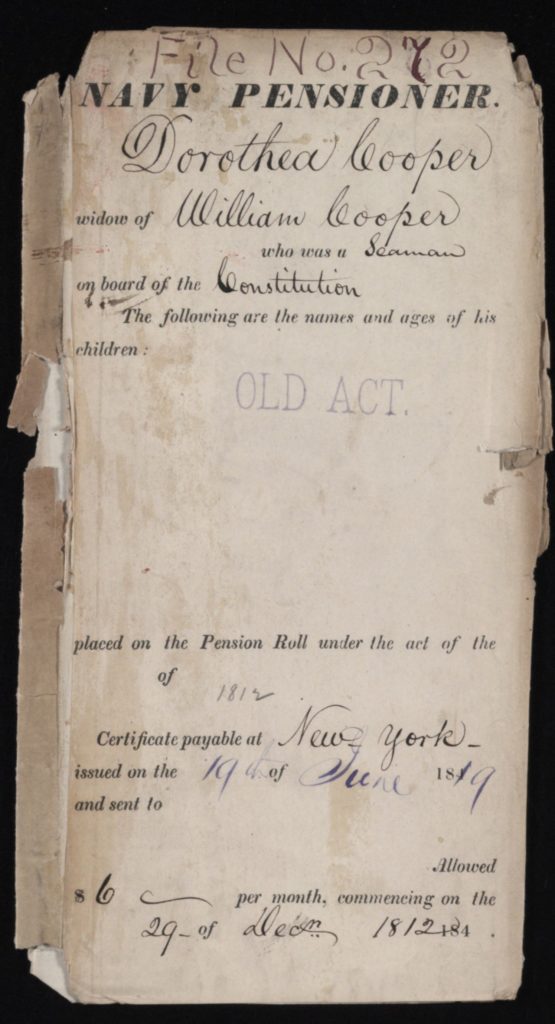

Six years later, in 1835, Dolly married 68-year-old Obidiah Cuffee. Obidiah, a recent widower, had several adult children of his own. He had spent most of his life working for the Floyd family, another large landowner near Poospatuck. In an 1886 memoir titled Sunny Memories of Mastic, Sarah Floyd Turner, a member of the Floyd family, described Obidiah and Dolly’s wedding as an elaborate affair that was attended by Unkechaugs from throughout eastern Long Island. According to Turner’s memoir, the Cuffees lived at Poospatuck until Obidiah’s death in 1847.

By 1854, Dolly was in her 60s and beginning to struggle both physically and financially. She lived at various times with her son, Nelson, or her daughter, Frances. With the help of a representative, she appealed again to the Naval Pension Office, claiming the money she had previously received in the 1810s and 1820s was “County money prize money and arrears of pay due her said husband [William Cooper] at his death.” She asked for the pension money, which she claimed she had not received, under the Acts of Congress passed in 1814, 1819, and 1824. She was awarded an increased pension that continued until her death.

* * *

This article has been made possible by a Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (#SHARP) grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.