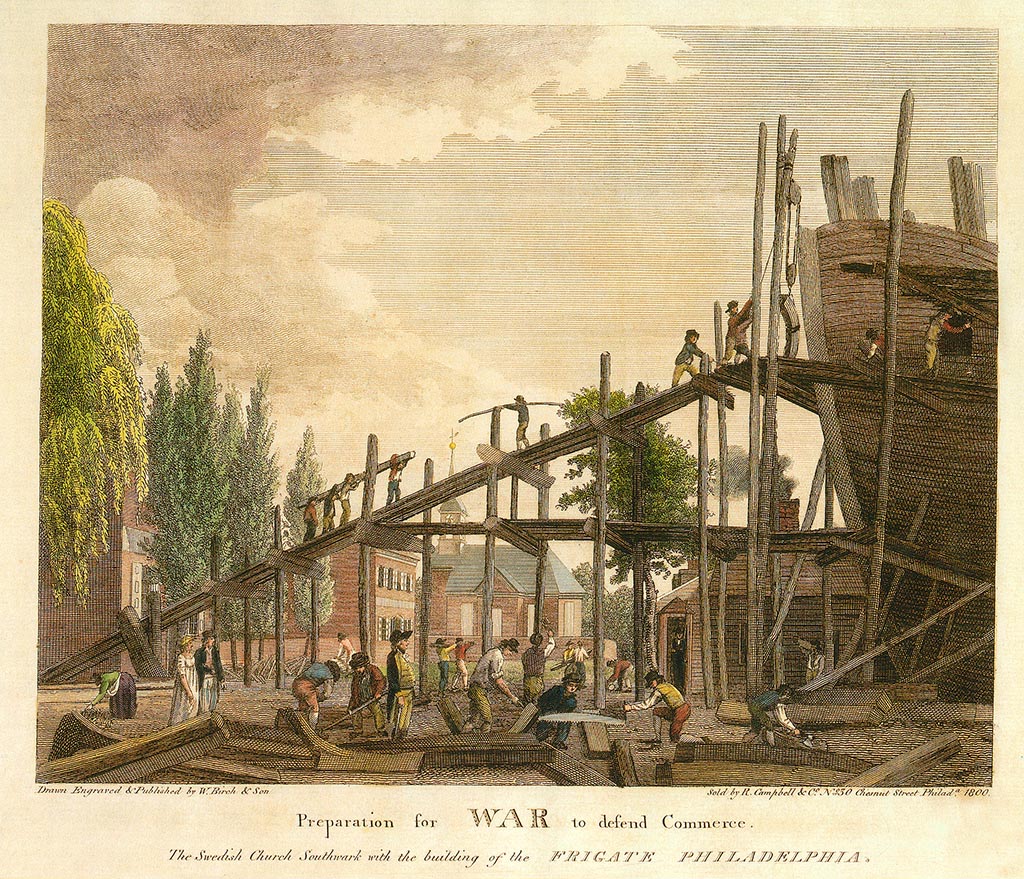

The decision in 1794 to build six frigates for a new United States Navy led to a huge procurement program for the nascent federal government. Sourcing live oak trees–a strong, durable, and rot-resistant timber–for the framing of the new frigates posed a particularly expensive and difficult task that became fraught with complications and setbacks. Live oak timber only existed along the coast in the southern states, where it was difficult to access and harvest. But the success of live oak timber in the construction of those early ships prompted the Navy to make it a central component of numerous other Navy ships for the growing fleet. Thanks to a grant from Mass Humanities, the USS Constitution Museum has conducted original research into this story, focusing on the history of enslaved people in live oak harvesting for USS Constitution and other early U.S. Navy ships.

St. Simons Island, Georgia, was at a turning point when the Navy’s live oak harvesting began in 1794. In the two years prior, several large tracts of wooded land on the island had been bought by plantation owners who planned to grow sea island cotton and other commodities. They were eager to see the land cleared of heavy timber, but it was grueling work. A dense underbrush of saw palmettos and other bushes and trees had to be cleared first, and the weight and hardness of the live oak wood itself, along with the awkward shape of the trees’ branches, made cutting difficult. The cutting also required precision if the awkwardly shaped branches and trunks were to be preserved for specific purposes in shipbuilding.

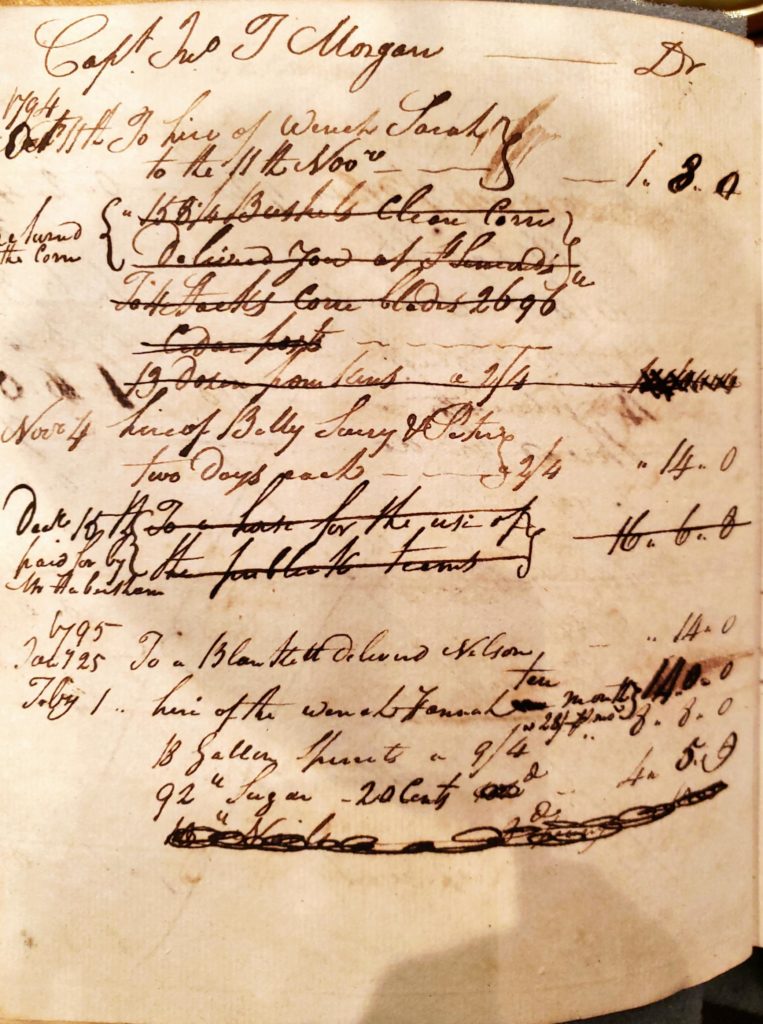

Commissioner of Revenue Tench Coxe, who was in charge of procurement for the U.S. Navy in the 1790s, sent Connecticut shipwright John Morgan to St. Simons Island in August 1794 to supervise a team of New England woodcutters in harvesting live oak. Morgan, who arrived at the worst time of the year, got little accomplished in the first months and failed to update Coxe with news of his difficulties. Having received no news from Morgan, Coxe sent Navy captain John Barry to the island in the fall to check on the progress.

Once Barry arrived, he began to look for enslaved laborers to assist with the work. Initially, Secretary of War Henry Knox noted that “some people,” likely shipwright and frigate designer Joshua Humphreys, had cautioned against using enslaved labor because the job would not be done correctly and would cost the government additional money.1 But with virtually no progress made since August, Barry sought local help. The New England woodcutters were responsible for designating which trees to cut and how, and enslaved people were tasked with the arduous work of clearing the underbrush and moving cut timbers. Barry later reported that Morgan had hired out six enslaved men from plantation owner James Spalding. Barry himself hired out 10 more from plantation owner John Couper.

Despite hiring difficulties, the eventual success of live oak in USS Constitution and other initial ships, as well as the immediate need for additional ships, prompted the government to invest in purchasing or setting aside other stands of live oaks. In 1800, the United States purchased the 5,600-acre Blackbeard Island, which is located just to the north of St. Simons Island. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Navy gained access to stands of live oak along the coast in the Gulf of Mexico. Live oak harvesting continued in these areas for decades, and enslaved labor continued to contribute to the work. Blackbeard Island is still owned by the federal government and is now the Blackbeard Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Both in the areas purchased by the government and on other privately contracted lands, the Navy turned increasingly to local labor, including both southern White woodcutters and enslaved Black laborers. In 1799, Phineas Miller of Cumberland Island, Georgia, was hired to provide live oak framing for six new 74-gun ships of the line. This incredible demand grossly outpaced what Miller was prepared to deliver, and he scrambled for additional labor in the form of paid ship’s carpenters and enslaved laborers. In newspaper ads in the spring of 1800, Miller sought to hire out “A whole gang of Negroes,” which he expected would include families with women employed in the cotton fields and men sent to assist with timber harvesting.3 The journal of James Keen, a Navy timber supervisor sent to Blackbeard Island in 1817, includes a list of all the workers on site, including 21 enslaved men, one enslaved woman, and her child. All of these people were provided by enslaver Thomas Newell of Savannah, whose grandfather had been one of the merchants facilitating the finances between the Navy and property owners in the 1790s.4

Today, much of the area of St. Simons Island where live oak was once harvested is preserved by the St. Simons Land Trust, which maintains the property as both a recreational and ecological preserve. Archaeological excavations of the earliest cotton plantation houses and slave quarters, as well as much earlier indigenous people’s shell middens are conducted there in cooperation with the Coastal Georgia Historical Society.

To learn more, watch this fascinating conversation with Justene Hill Edwards, Associate Professor in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, and Ryan Quintana, Associate Professor of History at Wellesley College:

1 “To Alexander Hamilton from Henry Knox, 21 April 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives & Records Administration.

2 Richard Leake plantation journal and business records, MS 485, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia.

3 Columbian Museum & Savannah Advertiser, April 4, 1800.

4 Virginia Steele Wood, “James Keen’s Journal of a Passage from Philadelphia to Blackbeard Island, Georgia, for Live Oak Timber, 1817-1818,” The American Neptune, 35 no. 4 (1975): 227-247.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.