April 2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride, when he raced across the countryside to warn of British troops on the march to attack at the start of the American Revolution. While Revere is forever etched in American history for his role in the nation’s fight for independence, his contributions extend more than 20 years beyond the Revolutionary War to the construction of one of America’s first naval frigates, USS Constitution.

A pioneering metallurgist, Revere supplied copper bolts and, later, copper sheathing for the hull of Constitution at a time when there was virtually no means of producing copper in the United States. In the process, Revere not only became a pioneer of the copper industry in America, but came to exemplify the changing nature of how industry worked, innovated, and grew.

An Evolving Revolutionary

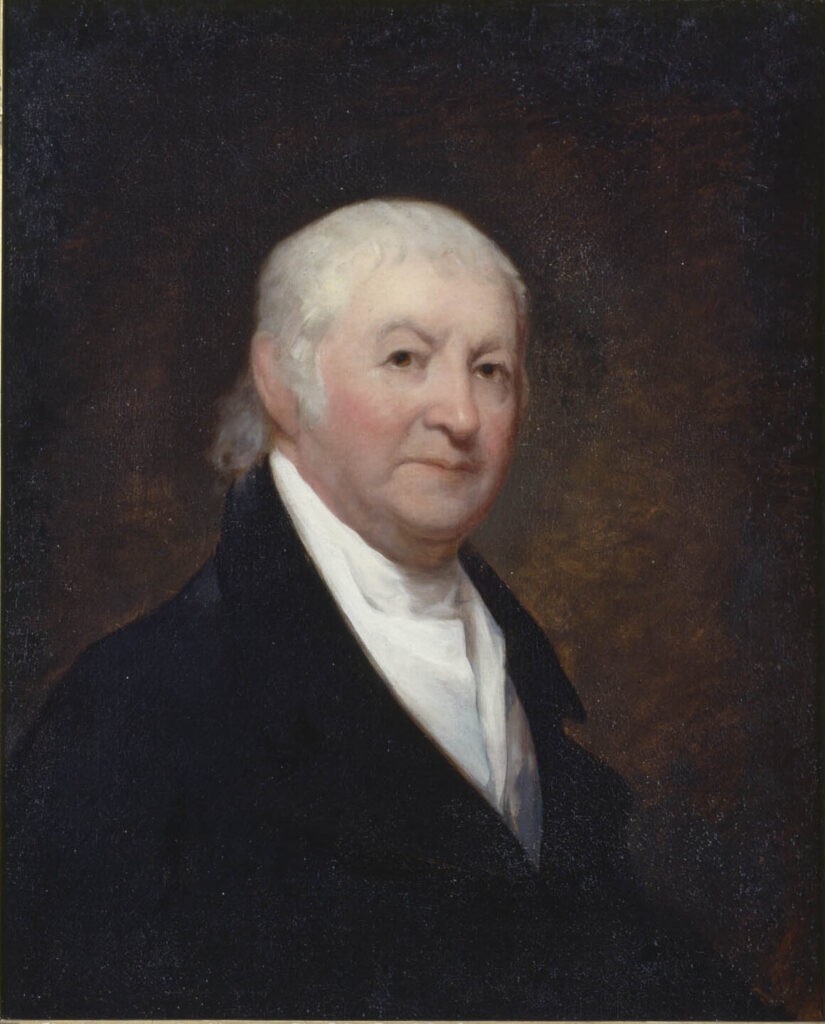

In 1775, Revere was a successful silversmith who had learned the trade from his father as a traditional apprentice, becoming an artisan who crafted unique silver pieces for a discerning clientele. He became active in the revolutionary cause early on and frequently leveraged his business and skills to support the movement. He produced an engraving of the Boston Massacre that helped spread news of the event, created printing plates for some of the first Continental currency, and expanded his business into the production of gunpowder for the Continental Army. In addition to his famous ride, he had also participated in the Boston Tea Party.

By the time of USS Constitution’s construction in the 1790s, Revere’s business and focus had changed radically. Following the Revolution, Revere began shifting his business model away from individually crafted silver pieces. Instead, he adopted a manufacturing-centered approach that allowed him to produce larger quantities of the same goods in a factory-like setting. This included a silver-plating mill that rolled out thin sheets of silver for use in a variety of objects. This process served as a precursor to Revere’s experience with rolling mills, the technology later used to roll sheets of copper for the bottom sheathing of USS Constitution.

Revere expanded from silver to iron when demands rose for domestically produced ironwork. As he began to mass produce durable iron tools, his business took on more of a modern factory model, with wage-earning workers replacing artisans and apprentices.

At this time, Revere also began to explore copper production, a move that would pose an entirely new set of challenges in a country where copper production was virtually non-existent.

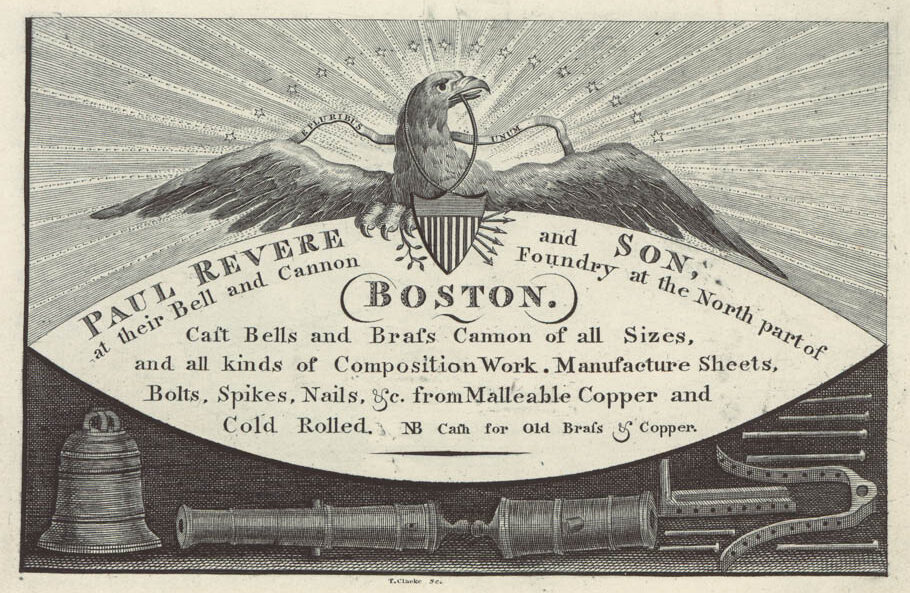

The use of copper in myriad applications and alloys goes back more than 6,000 years. Copper’s properties make it both uniquely valuable and notoriously difficult to work with. Handled incorrectly, it can become brittle and crack easily under strain. But with the right processes, it can be shaped into a variety of durable products that maintain its strength and hardness. Figuring out the best ways to work with copper to create different desired products is one of its sophisticated challenges. Mixed with tin, it creates bronze; with zinc, it creates brass – both hard alloys that improve on copper’s benefits without the drawbacks of pure copper. The results are extensive uses ranging from extremely fine tools and machinery to massive military cannons and church bells.

In addition to the difficulties associated with shaping it, copper requires a much higher degree of purification from the ground than other metals. While copper can be found in deposits by itself in ore, it is more often merged with other metals into minerals. Smelting, the process of extracting copper from the ore, requires heating and chemical processing to separate the other components.

For a long time, most of the copper found in the North American colonies was bound in sulfides that were particularly complex and difficult to smelt. Mining for this was not considered productive because the knowledge and facilities for smelting it did not exist in North America, and it was not worth shipping the ore back to England for smelting because more easily extractable forms of copper were in abundance there.

Copper deposits bound up in oxides left from prehistoric lava flows in Connecticut and New Jersey offered a much better source that was more easily smelted. Starting in the 1710s, mines throughout the region began producing copper, but due to the difficulties of working with it, and the higher demand for iron, there remained relatively little copper production in America, particularly compared to iron.

As a result, the copper used for products in the United States was almost exclusively derived from imported raw copper, usually from England.

Revere’s Industry Expands to Ships

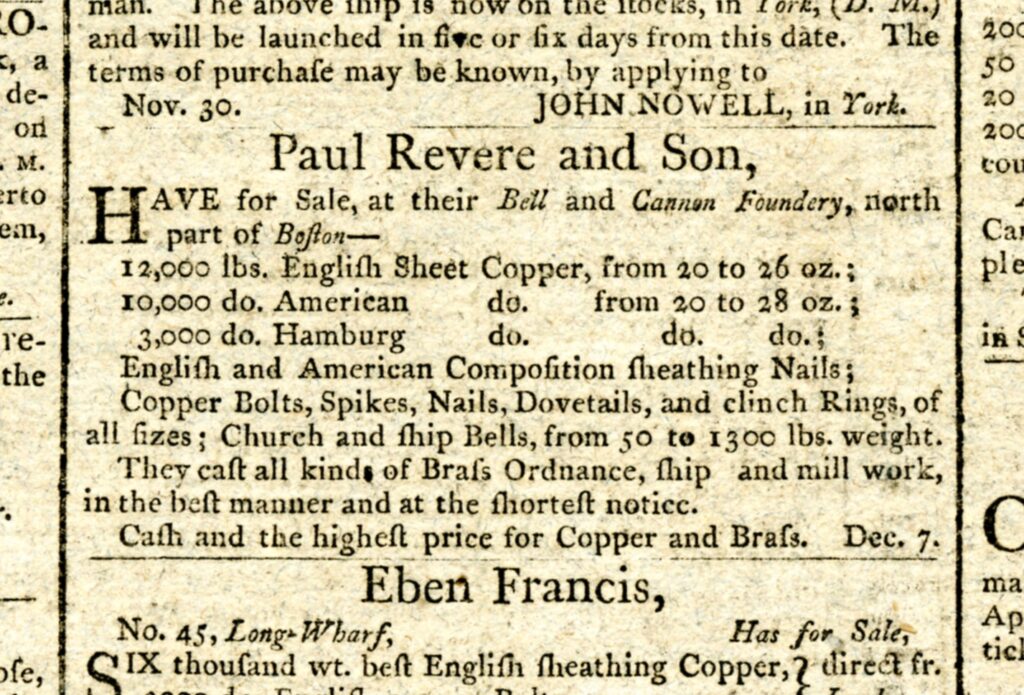

By the beginning of the 1790s, Revere’s business had expanded into copper. His extensive experience, first with silver, then iron, served him well as he tried to learn the nuances of working different types of copper, brass, and bronze into a variety of manufactured products. Initially, he made bells and cannons, but began working with bolts after the federal government decided to establish a standing navy in 1794.

Because it does not corrode in the same way as iron when exposed to seawater and salt spray, copper and its alloys were, and still are, important in manufacturing fittings and equipment for ships, ranging from precision navigational instruments to large bolts connecting timbers.

By the time of Constitution’s initial construction, Revere felt he could create the massive quantity of bolts needed, even if it required redrawing and reshaping English copper bolts to the sizes required for American frigates. A ship’s timbers are constantly subject to stress and strain from the motion through the winds and waves, and the bolts and spikes holding those timbers together require specific characteristics. Manufacturing the bolts and spikes requires a deep understanding of how the metal’s composition changes during the shaping process, as well as the ability to precisely control factors such as temperature.

For Revere, learning this process was key to producing bolts and spikes that met the Navy’s expectations. He began producing bolts for local shipyards and established his product reputation. In October 1795, he completed his first Navy contract for 15 tons of bolts. By the time Constitution set sail in 1798, Revere had provided more than 8,000 pounds of bolts, spikes, and staples to that ship alone.1

One huge copper element in USS Constitution’s initial construction that Revere did not supply was the copper sheathing used to cover the bottom of the ship’s hull. Creating the thin sheets was another metallurgical challenge that no one in America had yet achieved at the time of Constitution’s construction.

Covering or coating the bottom of wooden ship hulls is critical to preventing harmful marine growth. Barnacles and seaweeds attached to the hull create drag as the ship moves through the water, dramatically slowing it down and eventually damaging the wood. A greater threat to the hull’s integrity is Teredo Navalis, commonly known as shipworms. A small ocean clam with a wormlike shape, it attaches itself to the hull and then burrows into the wood, creating tunnels. The damage to the wood can easily sink ships, and the mollusks are particularly common in warm tropical and subtropical waters.

Efforts to deter shipworms included a variety of coatings and other sheathings designed to act as sacrificial layers that were regularly replaced. Tar and tar paper, lead sheathing, and additional layers of wood planking were used. It was not until the 1750s that the British developed the technology to create thin, flexible sheets of copper, which proved to be the best solution. Not only are copper sheets impermeable to the shipworms, it’s also toxic to and repels much of the marine life that would normally take hold on other sheathings or coatings.

Copper’s finicky nature meant that rolling out sheets of it was a highly precise, complex process. The British mastered the use of large iron rollers, which reduced bars of copper to sheets through repeated rolling. Like other copper shaping procedures, it required precise heating of the copper and iron rollers.

The widespread adoption of imported copper sheathing for ship construction didn’t take hold in America until the 1790s. Constitution’s original copper sheathing was British-made, while the fasteners holding it to the hull were manufactured by Revere. The development of a larger, standing United States Navy, along with the global expansion of U.S. trade, prompted American officials to support the establishment of a domestic copper supply and manufacturing technology to serve national interests. This included copper mining, refining, and manufacturing of copper equipment, including sheathing. It was a massive undertaking. The amount of copper needed to sheath just Constitution’s hull amounted to about 12,000 feet of rolled sheets.

Anticipating the need for rolled copper, Revere wrote to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert in 1798, assuring Stoddert that he could use his previous experience to learn to roll copper for the Navy, if only the government would loan him the money to develop the process. Stoddert declined, but by 1800, Revere was developing his own rolling machinery and process using domestically sourced and refined copper. Without any training or direct guidance from British experts, Revere’s methods employed all the lessons he had learned working in silver, iron, and other forms of copper. It was also a process of trial and error that had its failures and pitfalls. His early samples had questionable defects, and while Revere was quick to defend his work, he also continued to improve the product.

Revere did eventually secure funding from the government to provide sheathing, which helped him pay for the necessary equipment to develop copper refining and rolling at his existing mill in Canton, Massachusetts (now the Paul Revere Heritage Site). By 1801, he was providing copper sheathing to the Navy, including replacements to Constitution’s sheathing during its first major refit from 1802 to 1803.

In Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn, a biography of Revere and his businesses, MIT Professor Robert Martello argues that Revere’s career exemplified America’s shift from a colonial artisan/apprentice model of work to a more modern industrial system of manufacturing. His business methods, expansion into related fields, and growth in production capacity all came to represent the new United States, a rising industrial power that Revere had personally helped lead into sovereignty in the American Revolution.

In the process, his contributions to USS Constitution indelibly linked Paul Revere to “Old Ironsides” and the founding of the U.S. Navy.

_________________________________

1 As quoted in Robert Martello, Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise (Baltimore, Md. : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 196, 199.

Harris, J. R. “Copper and Shipping in the Eighteenth Century.” The Economic History Review 19, no. 3 (1966): 550–68.

Martello, Robert. Midnight Ride, Industrial Dawn: Paul Revere and the Growth of American Enterprise. Baltimore, Md. : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Young, Otis E. “Origins of the American Copper Industry.” Journal of the Early Republic 3, no. 2 (1983): 117–37.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.