On January 6, 1845, Midshipman Lucius Meade Mason died on board USS Constitution off the coast of Sumatra. The 20-year-old had been increasingly sick for more than a week – one of dozens of the crew who had contracted dysentery on the long voyage across the Indian Ocean from Africa. He was buried at sea.

“He wrote home from Zanzibar that we were all well. The next letter that his mother gets will tell her that the blue Indian Ocean is the grave of her son,” Mason’s friend and watchmate William Buckner wrote in his journal.

Mason’s untimely death in the service of this country was the ultimate sacrifice for both him and his family. In the small community of a ship’s crew at sea, every death is deeply felt, but rarely acknowledged in detail.

Descendant of the Revolution

Lucius Meade Mason was born on May 24, 1824, into an affluent plantation family in Alexandria, Virginia, with deep roots in the American Revolution. He had a twin sister, Eliza, who died at age 8.

His great-grandfather, George Mason, represented Virginia in the U.S. Constitutional Convention in 1787. He also drafted that state’s constitution and bill of rights, which served as a model for the later U.S. Bill of Rights. On paper, he was an early and vocal opponent of slavery despite enslaving many people himself. The family continued to enslave people on their plantations throughout Lucius’ lifetime.

Lucius Mason joined the Navy as a midshipman in October 1841, at age 17. The family had a long history of military service, and with two older brothers and five younger ones, Lucius also likely stood little chance of inheriting a viable livelihood in Alexandria.

He served initially on USS United States before transferring to USS Constitution on November 19, 1843, while the ship was undergoing a refit in Norfolk, Virginia.

A World Adventure

Mason joined Constitution as part of a crew that would take the ship on a two-year voyage around the world from 1844 to 1846. As a midshipman, he was an officer in training. Midshipmen had no specific responsibility and could be assigned to a variety of leadership roles and tasks designed to train them for future command.

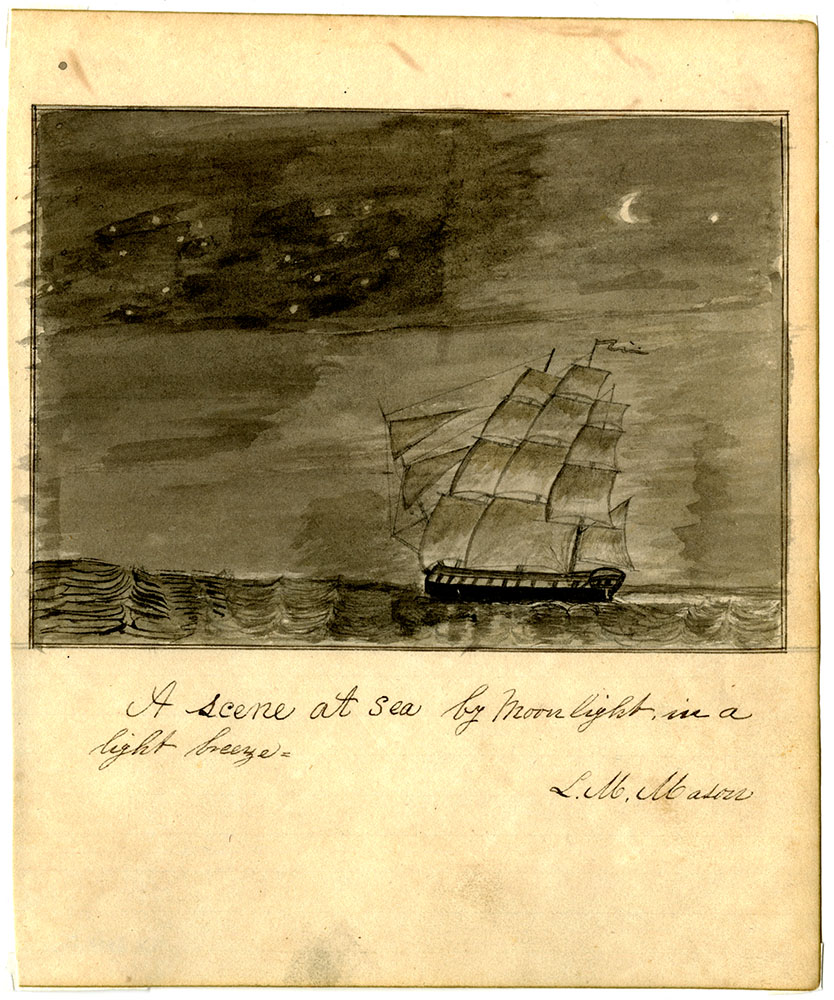

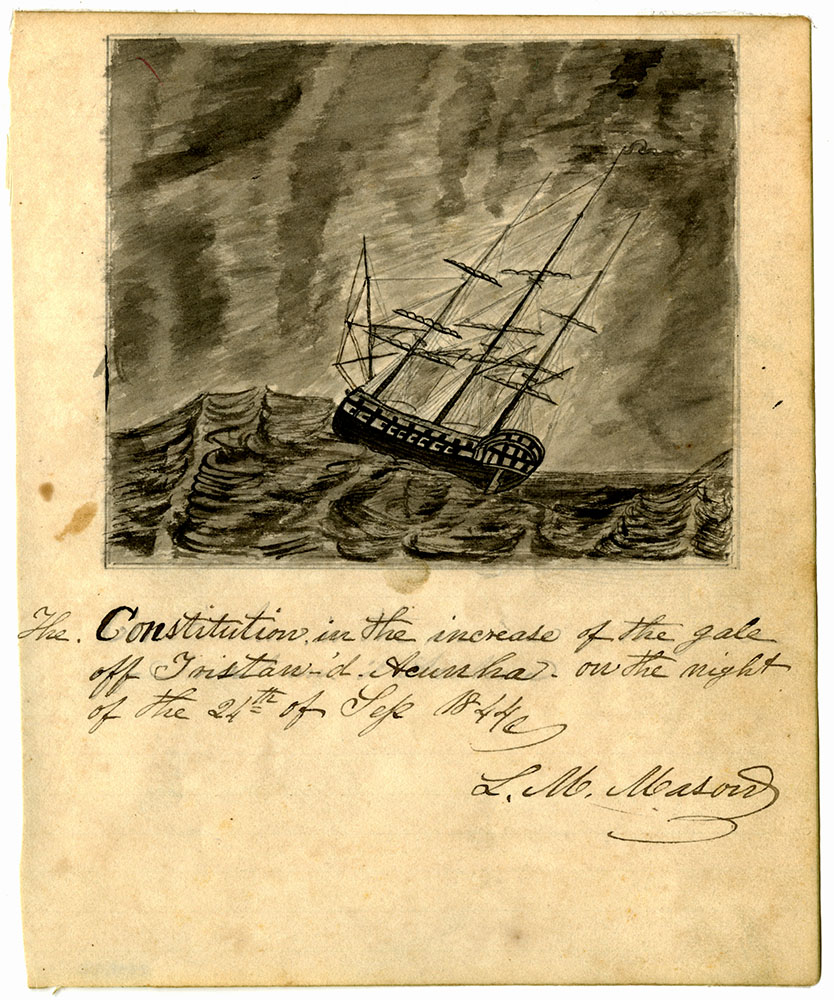

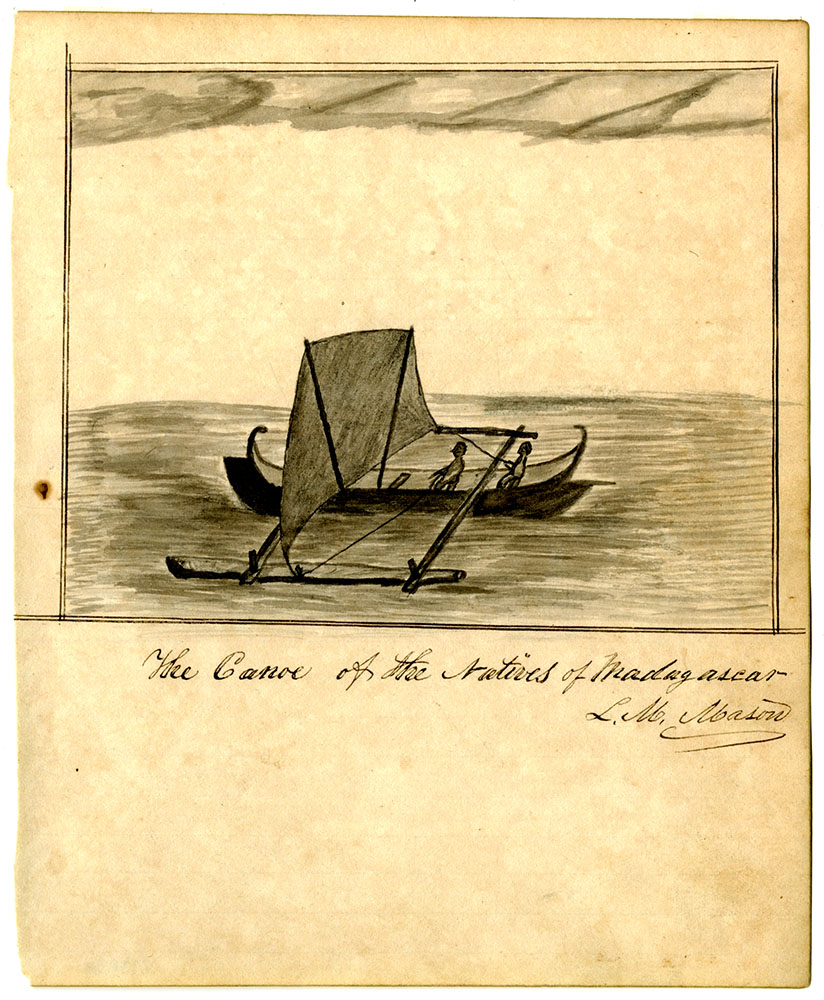

By all accounts he was doing well in his role and enjoying the adventure of world travel, though he did not acclimate to the difficulties of life at sea and looked forward to getting home. Along the way, Mason made sketches of the places he visited and sights he saw. He also kept a diligent midshipman’s journal, a duplicate of the ship’s logbook designed to teach logkeeping skills. Personal journals and accounts written by his shipmates repeatedly mention him by name, citing his impressions and descriptions of the exotic places they were visiting.

Mason’s apparently romantic image of going to sea was shattered by the reality of rounding the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. A bad storm kept Mason and others up in the rigging, reducing sail for half an hour. He later wrote, “no life can a man lead wherein he sees more hardship, and deprivation,” and “reaps less reputation.”

A Burial at Sea

On the long crossing of the Indian Ocean after departing Zanzibar, Mason fell ill with dysentery. Likely caused by drinking water obtained there, the illness struck a large number of the crew, including Captain John Percival. Mason’s condition continued to deteriorate over 10 days.

The ship reached Sumatra, but there was no relief for Mason. He died on the morning of January 6, 1845, shortly after the ship had left Quallah Battoo (Kuala Batu).

Buckner described in his journal the ceremony that followed in committing Mason’s body to the sea:

“He was laid out about the mizzenmast, with his sword, cap, coat, etc. At the appointed time all hands were called, the main topsail laid to the mast, his messmates ranged themselves on each side, his body was carried by four quartermasters, our first lieutenant read prayers and the dead march as we moved toward the gangway. At the proper time he launched overboard. The marine guard fired a volley over his grave.”

As watchmates, messmates, and fellow midshipmen, Buckner and Mason spent a lot of time together and became close friends. Both Mason’s death, as well as the anonymity of a burial at sea, struck Buckner hard and he grappled with it in his journal:

“Many a tedious mid-watch hour I passed with Mason, which we would generally spend talking of our homes, what we intended to do when we got back. Then we would often talk of our sisters, and what presents we intended to buy to take home to them. He wrote home from Zanzibar that we were all well. The next letter that his mother gets will tell her that the blue Indian Ocean is the grave of her son. There is something I cannot describe so mournful in a burial at sea that it weighs upon one’s mind more than all the preachers can say ashore. And then to lose a messmate and watchmate is like losing one of a family, and makes a blank, a vacancy, that nothing can fill up.”

___________________________________

Mason’s quotes from his letterbook as cited by ship’s carpenter Henry George Thomas in Thomas’ account, Around the World in Old Ironsides: The Voyage of USS Constitution, 1844-1846 (Lively, Va. : Chesapeake, Va: Norfolk County Historical Society, 1993).

Buckner quotes from Tales of the Sea: Correspondence of William Perry Buckner, a scrapbook of his correspondence republished in the Arkansas Democrat newspaper. (USS Constitution Museum Collection. R. Dale Cooper III Gift, 2499.2)

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.