On June 10, 1785, the Continental Navy frigate Alliance, the last remaining ship in the Continental Navy, was officially put up for sale by the U.S. government. It was sold at auction two months later, leaving the fledgling United States government with no navy of any sort.

Established 10 years earlier, at the outset of the American Revolution, the Continental Navy was no longer considered feasible or necessary at the end of the war. Struggling under debt, the new nation showed little interest in maintaining the ships. One-by-one the ships were auctioned off by Superintendent of Finance, Robert Morris, who was given control of the Navy by Congress.

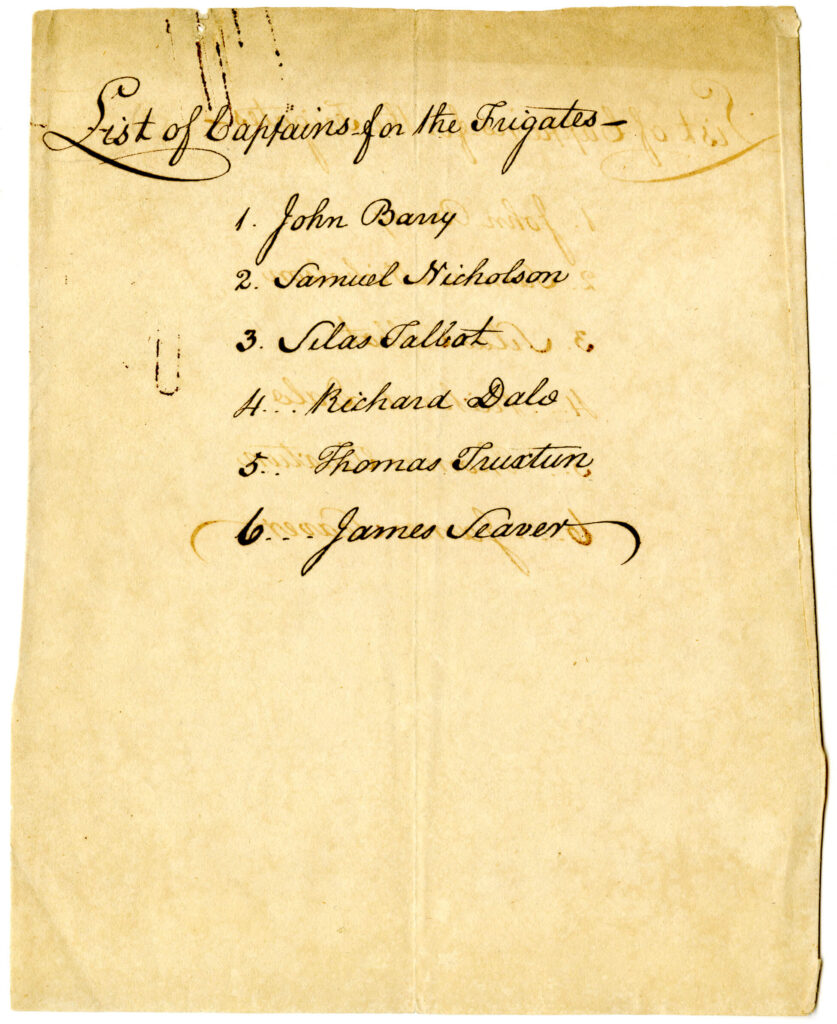

Congress did not fund another standing Navy until 1794, when it authorized construction of USS Constitution and five other new frigates, as well as the purchase of numerous other smaller ships converted for naval service.

The Continental Navy of 1775 and the U.S. Navy of 1794 were connected by a legacy of captains and crew who returned to naval service in the new force, but the circumstances establishing each of the navies were wildly different. As a result, their goals, ships and the obstacles they faced created very different navies.

A Local Force

Established months before the formal Declaration of Independence, the Continental Navy was not initially intended to take on the indominable British Royal Navy. Rather, George Washington and others were looking for a way to cut off the British shipping that was keeping British troops supplied with munitions and provisions in Boston.

For months before the Continental Congress even approved a formal Navy, Washington hired colonial schooners to seize British merchant ships bringing supplies to British ships. The first of these was the merchant schooner Hannah from Marblehead, Massachusetts, equipped with just enough weapons and crew to capture other merchant ships. Similar other schooners were soon added – small, easily manned vessels that could operate inshore and along the coastline.

A Step toward Nationhood

The decision to expand and formalize these efforts into a Continental Navy was not an easy one for the Continental Congress. “The maddest idea in the world,” one Maryland delegate famously called it. In addition to grappling with the cost of such an effort, some opponents feared that it would attract a wrathful response of the massive British Royal Navy. The prospect of launching a navy represented a claim to sovereignty when some still hoped for a resolution to the conflict that would keep America in the British sphere.

Initially Congress funded the purchase and arming of eight ships, but a Naval Committee eventually recommended construction of 13 frigates, to be built in ports from Massachusetts to Maryland. Much smaller and lighter than Constitution and the other later frigates of the 1790s, these ships were intended to protect the coastline and defend American shipping. Only eight of those frigates were completed and survived to serve on the open ocean. Others were either destroyed to prevent capture by the British or were seized on inshore waters.

A Maritime Nation without a Navy

By the time the frigate Alliance was sold off in the summer of 1785, American merchant ships were already facing difficulty in the Mediterranean. The war had suppressed America’s lucrative trade in the Mediterranean, and American merchants were eager to resume business there. Recognizing that American merchants were no longer protected by the Royal Navy, the Barbary states of the North African coast began attacking U.S. merchant shipping in the Mediterranean and ransoming crew. They insisted on regular tribute from the United States in exchange for free passage of U.S. merchant ships.

Initially that tribute was paid but demands continued to increase. Without a means of responding with force, the United States faced a choice of continuing to pay, suffer the losses, or withdraw from trade in the region.

The Debate over a New Navy

Congress’ decision in 1794 to fund a Navy was even more contentious than the funding of the Continental Navy. The United States Constitution, which was ratified in the interim, allowed for a federal navy but required Congressional approval to fund the expense.

Rather than just the coastal defense and raiding purposes served by the Continental Navy, the new Navy was explicitly designed to transit the Atlantic and serve on station for months at a time in the Mediterranean Sea. This not only meant larger ships, but an administration capable of providing the support needed to keep the ships manned and supplied across the globe.

Opponents debated the role of the federal government in protecting private business interests abroad and questioned the long-term benefit and cost. The conflict with the Barbary states was seen as an isolated, temporary need, they argued, and the oceans naturally protected the North American continent from foreign naval attacks.

Shifting Threats

When Congress ultimately approved funding for a new Navy, it did so by a very slim margin and with the provision that, if peace was made in the Mediterranean before the ships were completed, construction would cease. That provision was triggered by a deal with Algiers; however, the halt on construction proved temporary. Within a few months, French privateers began attacking American merchants in the Caribbean. France, following its own revolution, was again at war with Britain, and saw America’s neutrality as a repudiation of their former alliance during the American Revolution. In addition, following the French Revolution, the United States had ceased war debt payments owed to the old French government.

As a result, USS Constitution and the other new U.S. Navy ships were first deployed to the Caribbean and along the American coast to prevent American merchant ships from being seized by French privateers.

A Lasting Legacy

For the new U.S. Navy, the naval defense of America meant protecting American merchant ships wherever they were in the world – a mission USS Constitution pursued throughout its active sailing career and still represents today as the only surviving member of that original fleet.

As a symbol of that heritage, Constitution, launched more than a decade after the American Revolution, continues to represent the autonomy and sovereignty of a new nation at sea that was established with the founding of the Continental Navy.

___________________

Sources

Chapelle, Howard Irving. The History of the American Sailing Navy: The Ships and Their Development. Konecky, 1988.

Fowler, William M. Rebels Under Sail: The American Navy During the Revolution. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976.

Hearn, Chester G. George Washington’s Schooners: The First American Navy. Naval Institute Press, 1995.

Miller, Nathan. Sea of Glory: The Continental Navy Fights for Independence, 1775-1783. D. McKay Co, 1974.

Naval Documents of the American Revolution. 13 vols. Naval History Division, Department of the Navy; Naval History and Heritage Command, 1966-2019.

Smelser, Marshall. The Congress Founds the Navy, 1787-1798. University of Notre Dame Press, 1959.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. First published as a Norton paperback. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Willis, Sam. The Struggle for Sea Power: A Naval History of the American Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. The Oxford History of the United States 3. Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Author(s)

Carl Herzog

Public Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Carl Herzog is the Public Historian at the USS Constitution Museum.