One of the more charming human traits of long standing is our penchant for naming inanimate objects that play important roles in our lives. We name our boats, our cars, and our houses. Psychologists will have much to say about this, no doubt, but it seems we anthropomorphize things to establish a relationship, transforming a commodity into something almost human.

American sailors of the early nineteenth century evinced the same predilection, only in their case they named the cannons they served in battle. On board ship, the crew was divided into two different social groups. Seamen ate together and socialized in messes. But when the drumbeat called them to battle stations, or “quarters,” they fought as members of a gun crew. On the large frigates, as many as 14 men struggled to load, fire, run in, and run out a three-ton behemoth of iron and oak. Such labor, and the careful attention it took by all involved to prevent deadly accidents, must have created a connection between the men and their particular cannon.

And so they named their guns. Some names were humorous or playful. Others celebrated American heroes or political ideals. Still others played up the deadly nature of the gun.

Folk traditions, commonplace practices or superstitions, are notoriously hard to resurrect. Frequently they pass away unnoticed, but in this case, the sailor names got memorialized by official navy documents.

An 1811 watch and quarter bill for the frigate United States (now at the Library of Congress) gives the names of its guns, including some unwarlike sobriquets: Long Nose Nancy, Brother Jonathan, Jumping Billy, Happy Jack, and Hog and Hommany [sic].1

After HMS Shannon captured USS Chesapeake off Boston Light on June 1, 1813, the British took the ship to Halifax, where Royal Navy officers came to examine the first of the American frigates taken in the war. Historian William James, in his 1817 book on the war, had this to say:

The Chesapeake‘s guns had all names, engraven on small squares of copper-plate. To give some idea of American taste in these matters, here follow the names of her guns upon one broadside: – Main-deck; “Brother Jonathan, True Blue, Yankee Protection, Putnam, Raging Eagle, Viper, General Warren, Mad Anthony, America, Washington, Liberty for Ever, Dreadnought, Defiance, Liberty or Death.” – Forecastle; “United Tars,” shifting 18-pounder, “Jumping Billy, Ratler,” carronades. Quarter-deck; “Bull-dog, Spitfire, Nancy Dawson, Revenge, Bunker’s Hill, Pocohantas, Towser, Wilful Murder,” carronades; total 25.2

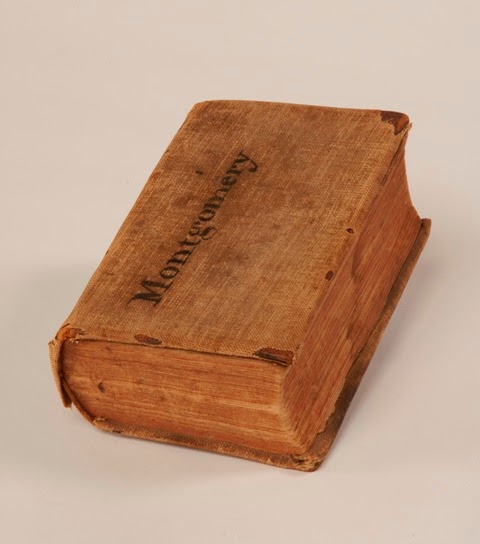

Perhaps the most touching evidence for this practice among American seamen can be found in the USS Constitution Museum’s collection. In 1813 or 1814, the Bible Society at Princeton University presented the sailors of USS President with a number of bibles. The sailors took the books, carefully wrapped the covers in duck cloth, and in this case lettered the word “Montgomery” on the front.

When we open the cover, we find the flyleaf inscribed with the following:

“Be it known that this Bible was taken from the Montgomery gun of the President Frigate where it was slung to the carriage of the said gun. It was taken by William Clark from where it hung after the engagement with the said Frigate, in December 1814 [sic]. He being master at arms and one of those that boarded the said President Frigate and as a further explanation, every gun of the said Frigate was named after some general or patriot of the United States and there was a Bible slung to the carriage of each gun and had the same name marked on the cover. This Bible was kept by me in remembrance of my brother the said William Clark, who departed this life in January 1819. Charles Clark.”

The frigate President, commanded by Stephen Decatur, sailed from New York on the night of January 14, 1815. The next day, a British squadron composed of four frigates chased and then beat the American ship into submission. William Clark, master-at-arms on board HMS Tenedos or Pomone, was among those who boarded the defeated vessel. He removed this Bible from the gun named for General Richard Montgomery, who fell during the American attack on Quebec in December 1775. While the book corroborates other evidence that guns on American warships were named by their crews, it also speaks to the religious feeling of seamen. It has been said that “there are no Sundays off soundings,” meaning at sea, few sailors adhered to the strictures of religious teaching. Indeed, seamen were notorious for being profanely irreligious. The Reverend Edward Mangin, chaplain of HMS Gloucester in 1812, wrote that “nothing can possibly be more unsuitably or more awkwardly situated than a clergyman in a ship of war; every object around him is at variance with the sensibilities of a rational and enlightened mind.” This Bible would seem to be at odds with these sentiments. Tucked into the cheekpiece of the gun’s carriage, we can imagine the gun crew reading from it during the long, tense hours of the chase. Even if they never cracked the covers, the Bible’s presence on the engine of destruction turned the book into a sort of talisman, a charm to ward off evil and a promise of salvation should the worst happen.

If sailors on United States, President, and Chesapeake all named their guns, it is a good bet that Constitution’s seamen did to. To date, we’ve never found any record of the names they might have given them, besides an example scratched on a powder horn that belonged to the ship’s gunner in the 1820s. The names currently painted on plaques over the ship’s guns seem to have come from those given to the United States’ and Chesapeake’s.

1 Quoted in Ira Dye, The Fatal Cruise of the Argus (Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 77.

2 William James, A Full and Correct Account of the Chief Naval Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America (London: T. Egerton, 1817), 232.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.