“[Our frigates] should combine such qualities of strength, durability, swiftness of sailing, and force, as to render them equal, if not superior, to any frigates belonging to any of the European Powers.”

– Secretary of War Henry Knox, December 27, 1794.

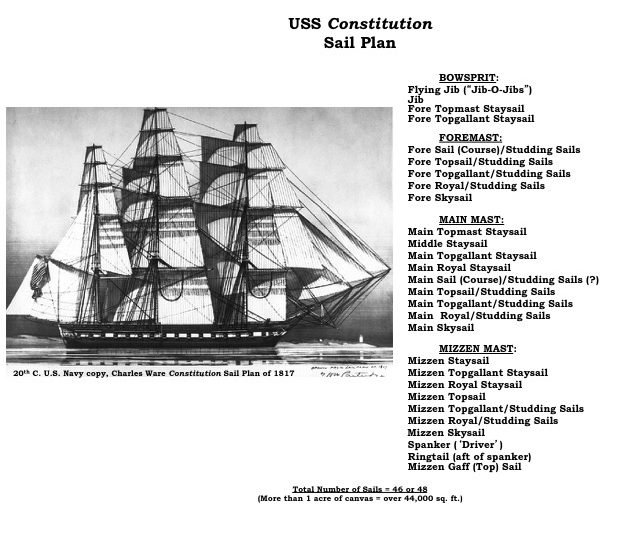

The rig aloft is a sailing warship’s engine, and USS Constitution‘s speed and maneuverability during her active years were the result not only of a sleek hull, but also of her very tall sailing rig. Shipbuilder Joshua Humphreys designed the original six frigates to be “the most powerful, and, at the same time, the most useful ships…it is expected the commanders of them will have it in their power to engage, or not, any ship, as they may think proper…” [Report by Joshua Humphreys, Naval Constructor, December 23, 1794.] “Old Ironsides'” numerous sails supplied the power needed to drive the ship in ocean passages and the swiftness needed to escape or chase the enemy as required.

The earliest known painting of Constitution (below), attributed to Michele Felice Cornè, shows the ship with much of her complement of sails set. The painting gives a sense of the size and power of Constitution‘s rig. The ship’s main sail measured 77 feet wide at the top, over 87 feet at the bottom, and 45 feet tall. The impressive scale of the sails is illustrated in the detail below, which depicts the crew working aloft and barely visible amongst the enormous sails.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 296.1]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2-296-1_001-1024x793.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 296.1]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/3-296-1_001detail-1024x461.jpg)

Before, during, and after battle, nearly half of Constitution‘s approximately 450-man crew would be actively engaged with the setting and furling of select sails. In his August 28, 1812 letter to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton, Captain Isaac Hull wrote of the preparations for battle with HMS Guerriere: “I immediately ordered the light sails taken in…took two reefs in the topsails, hauled up the foresail, and the mainsail and see [sic] all clear for action…” These sail preparations are illustrated in a painting below by George Ropes, Jr. in 1813.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 2094.1]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/4-2094-1_001-1024x761.jpg)

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 2094.1]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/5-2094-1_001detail.jpg)

The detail above from Ropes’ painting clearly illustrates the vast manpower needed to reef (shorten the sail area exposed to the wind) or furl the big, deep topsails on Constitution. First Lieutenant Ellie Vallette, who served aboard Constitution in the mid-1820s, kept a “watch and quarter bill” (shown below), delineating the duties of every officer and sailor aboard ship at all times. Three pages of the manuscript not only show how many men were required on each yard when setting and furling sail, but also lists the names of the individuals assigned to each position. The main top yard from which the main top sail hangs required a minimum of 32 men–16 on each side–to bring in the heavy flax sail.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 1783.3]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/6-1783.3_001-1024x728.jpg)

Vessels rigged as a ship are the most complicated of all sailing rigs, and the task of setting and furling sail was physically taxing for the crew. Sailors were required to train extensively both on the guns and aloft in the rigging. When a battle or storm occurred, each person knew his station and the tasks expected of him. Hours of training, however, made the job no less dangerous. The crew who worked aloft wore no safety harnesses or any other gear to protect them from the wildly pitching motion of the masts or the snapping and billowing of the sail over their heads.

“The boatswain’s whistle was heard, followed by the shrill cry for ‘All hands take in sail! jump, men, and save ship!’…We found the frigate leaning over…so steeply…The vessel seemed to be sailing on her side…With every lurch to leeward the yard-arm-ends seemed to dip in the sea, while forward the spray dashed over the bows in cataracts, and drenched the men who were on the fore-yard.”

– White-Jacket, or The World in a Man-of-War, by Herman Melville, 1850.

![[USS Constitution Museum Collection, 2112.1]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/7-2112-1_001-1024x998.jpg)

Constitution‘s original sails were made from flax, a heavy and durable fiber that was used by the U.S. Navy well into the 19th century. Each of the six frigates was “provided [with] one suit of sails… [The sail cloth] was contracted for, and manufactured in the United States, in the year 1794.” [Report by Timothy Pickering, War Office, December 12, 1795.] By the end of the 1800s, the Navy, like the merchant service, made the transition to cotton canvas. The term “duck” was frequently used in reference to sail material, denoting a super quality of fiber. The word “duck” comes from the 17th century Dutch doeck denoting ‘linnen or linnen cloath’ [Oxford English Dictionary]. Constitution‘s original suit of sails were sewn in the Granary, at the present-day location of the Park Street Church in the center of Boston.

The Navy was rapidly transitioning to steam power by the late 19th century, yet learning to sail on a traditional square-rigged sailing vessel remained essential training for midshipmen. The only known photograph of “Old Ironsides” under sail was taken at the end of her active sailing career in the summer of 1881 when she sailed with midshipmen. By this time, Constitution‘s flax sails had been replaced with heavy cotton canvas.

![[Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/9-1881SailCrop-1024x687.jpg)

After USS Constitution‘s substantial 1927-1931 restoration, the U.S. Navy recommissioned the ship on July 1, 1931. She was sent out on her three-coast National Cruise to thank American school children who had given pennies to the cause and others who had donated materials to aid in the rebuilding. Before departing from Boston, the ship was outfitted with 32 sails, nearly her full complement, made with donated cotton duck from Wellington, Sears & Co. of New York.

![Textile World, Volume 60, Issues 14-27. [Courtesy Google Books]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/cottonduckad.jpg)

Twenty-four different sail lofts from Maine to Texas, from New York to Chicago, assisted 21 Boston Navy Yard sailmakers in manufacturing Constitution‘s first suit of sails since 1881.

![[Courtesy Naval History Heritage Command Detachment Boston]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/sailmakers001-840x1024.jpg)

The staged photograph below from 1930-1931 shows two sailmakers who likely worked in the Boston Navy Yard sail loft. Note the “Oceanic Cotton Duck” logo stamped on the sail. This was the material that was supplied by the Wellington, Sears & Co.

![[Courtesy USS Constitution Museum]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/10-145_583276-1024x814.jpg)

Although Constitution was outfitted with a nearly full suit of sail for the 1931-1934 three-coast National Cruise, she was towed by the minesweeper USS Greebe from port to port. However, in late 1933 while the ship was in San Diego, Lieutenant William F. Royall was transferred to Constitution to become her sailing master. Royall organized the crew for dockside sail handling demonstrations with the intention of actually sailing “Old Ironsides” under her own power. Several opportunities to sail the ship were lost due to unforeseen circumstances, but on the day before Constitution returned to Boston on May 7, 1934, Commander Louis J. Gulliver announced that the ship would sail into Boston Harbor. As Royall recounted 63 years later, “…as we approached Boston, the wind failed us and fell into an absolute calm. Our sailing days were over.”

![[Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/13-1931CrewFurlingMainsail-1024x671.jpg)

“Old Ironsides” was given another chance to sail under her own power on July 21, 1997 under the command of CDR Michael C. Beck. It was the ship’s 200th anniversary, and Beck used this opportunity to celebrate the ship’s embodiment of the U.S. Navy’s ideals of honor, courage, and commitment. It had been 116 years since Constitution‘s last sail. Beginning in the spring of 1996, Constitution‘s crew trained aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Eagle, Brig Niagara and HMS Bounty to relearn how to sail a sailing frigate.

Constitution was rigged with six sails: two jibs, three topsails, and the spanker. The three topsails were made by Nathaniel Wilson of East Boothbay, Maine, one of the last sailmakers capable of manufacturing square sails of the size needed for USS Constitution. The Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston made the spanker and flying jib, and James Brink of Brooklyn, New York made the jib. The new sails were made from a Dacron fiber called Oceanus, by North Cloth of Milford, Connecticut. This synthetic material closely resembles natural canvas but, unlike cotton duck, does not absorb water and therefore weighs the same wet or dry. This is a clear advantage when handling sails as large as Constitution‘s.

![[Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/14-USSC21July1997Sail-685x1024.jpg)

![[Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/16-IMG_3063-Copy-909x1024.jpg)

USS Constitution sailed again for the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, commemorating 200 years of peace between Great Britain and the United States and Canada and the United States. This short sail took place at the entrance to Boston Harbor on August 19, 2012. Joshua Humphreys would be astonished and proud to know that, over 200 years later, one of his six frigates is the world’s oldest ship capable of sailing under her own power.

_____

The activity that is the subject of this blog article has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Maritime Heritage Grant program, administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Secretary of the Commonwealth William Francis Galvin, Chairman. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior, or the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

The Author(s)

Margherita Desy, Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston

Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command

Margherita M. Desy is the Historian for USS Constitution at Naval History and Heritage Command Detachment Boston.

Kate Monea

Manager of Curatorial Affairs, USS Constitution Museum

Kate Monea is the Manager of Curatorial Affairs at the USS Constitution Museum.