In the age before accurate charts marking depths and hazards to navigation, sailing a ship along an unfamiliar coast could be a dangerous business. Imprecise methods used to determine a ship’s location compounded the problem. Even the best navigators sometimes found themselves in uncomfortable situations. Groundings and strandings remained an inescapable, and often fatal, part of a seafaring life.

Captain William Bainbridge discovered this the hard way when he ran USS Philadelphia onto an uncharted reef off Tripoli during the Barbary Wars. Oliver Hazard Perry wrecked the schooner Revenge on a reef off Watch Hill, Rhode Island in 1811. USS President, under the command of Stephen Decatur, struck a sand bar at the mouth of New York Harbor while trying to run through the British blockade in January 1815. The ship was damaged enough to impede its sailing qualities, leading to its capture a day later.

Constitution suffered its own share of mishaps during its long career. The first recorded grounding occurred off Cape Francois, Santo Domingo in July 1800. As Constitution sailed from the harbor, the wind shifted, taking the sails aback and forcing the ship stern first onto a reef. “The Shock was sensibly felt and Violently repeated,” as reported in the logbook. After 47 minutes of shifting stores and heaving up anchors, the ship floated free without too much damage. Nevertheless, Sailing Master Nathaniel Haraden reported several years later that the ship, now “in ordinary,” seemed to make a considerable amount of water, probably because of the grounding off Cape Francois.

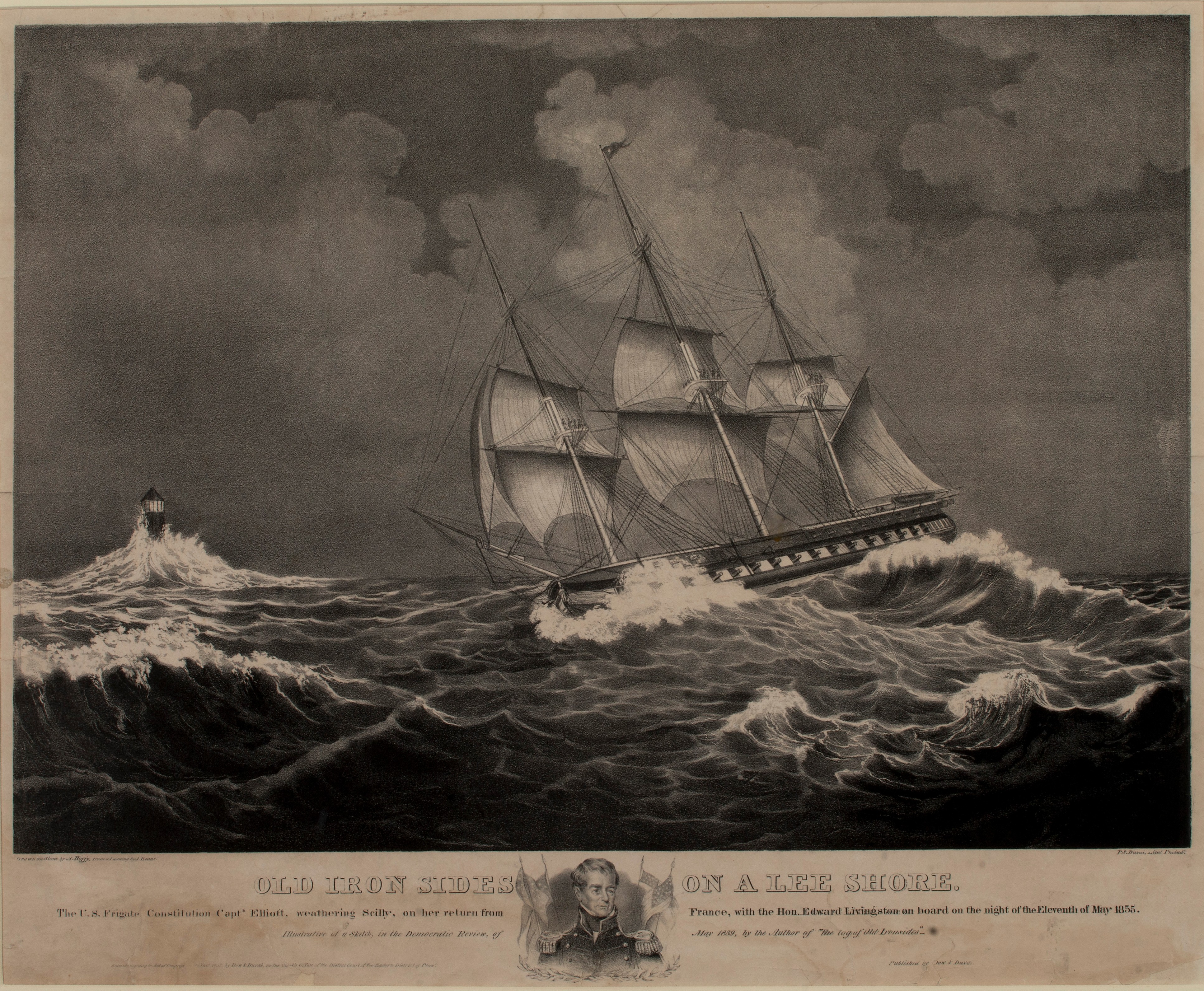

On the night of May 16, 1835, Constitution very nearly came to grief on the Scilly Isles at the western end of the English Channel. Returning from France with Minister Edward Livingston on board, the ship struggled against strong winds as it beat down the channel. That night, the officer of the watch reduced sail, but the winds blew the ship farther to leeward than expected. When the lookouts discovered breakers ahead, Captain Jesse Duncan Elliot boldly ordered more sail set to claw off the lee shore. The ship barely squeaked by, running at nine knots through the foaming sea, but at last left the dangers of the shore behind.

The Author(s)

Matthew Brenckle

Research Historian, USS Constitution Museum

Matthew Brenckle was the Research Historian at the USS Constitution Museum from 2006 to 2016.